Oppy, by Daniel Oakman

A biography of Hubert Opperman

Title: Oppy – The Life of Sir Hubert Opperman

Author: Daniel Oakman

Publisher: Melbourne Books

Year: 2018

Pages: 375

Order: Melbourne Books (Kindle edition also available on Amazon)

What it is: A biography of Hubert Opperman

Strengths: Oakman covers the cycling and political careers of Opperman and shows there was a lot more to him than one Tour de France

Weaknesses: Sporting and political biographies tend to focus on events, not people

Paris-Brest-Paris was one of the first major road races to be created, in 1891, a twelve hundred kilometre riposte to Bordeaux-Paris that, in its first edition, managed to attract more than two hundred riders. It helped to create one of cycling’s first true stars, Charles Terront. It was, though, a race too big for many and it didn’t feature on the following year’s racing calendar.

In fact, it didn’t feature on the racing calendar again until 1901, when it was resurrected and relaunched as a race so difficult it could only be held once every ten years. And the stars flocked to it. Lucien Lesna, Hippolyte Aucouturier, Maurice Garin, Gaston Rivierre, names that would all feature among the pre-race favourites when the Tour de France was launched two years later. The stars came again in 1911 and 1921. But come 1931 the world of cycling was changing, and only twenty-eight riders lined up to contest the fifth edition of the race. In among those twenty-eight were stars of the sport, past, present and future.

Nicolas Frantz was there, a two-time winner of the Tour de France. And so was Antonin Magne, the reigning champion of the grande boucle. Bernard Van Rysselberghe, winner of Bordeaux-Paris, was there. Jef Demuysère, a Lion of Flanders, one of the Tour’s grimpeurs, and later a winner of Milan-Sanremo, he was there. As was Frans Bonduel, winner of the Ronde van Vlaanderen. And Giuseppe Pancera, who’d come oh so close to victory in both the Tour and the Giro. And Marcel Bidot, future manager of the French national team at the Tour, shepherding the squad to victory six times in twelve tries. Others included Benoît Faure, Émile Joly, Léon Louyet, Émile Decroix, Marcel Huot, Jef Mauclair, Ernest Mottard, names that were known to the fans then, even if – like the race itself – half forgotten to us now.

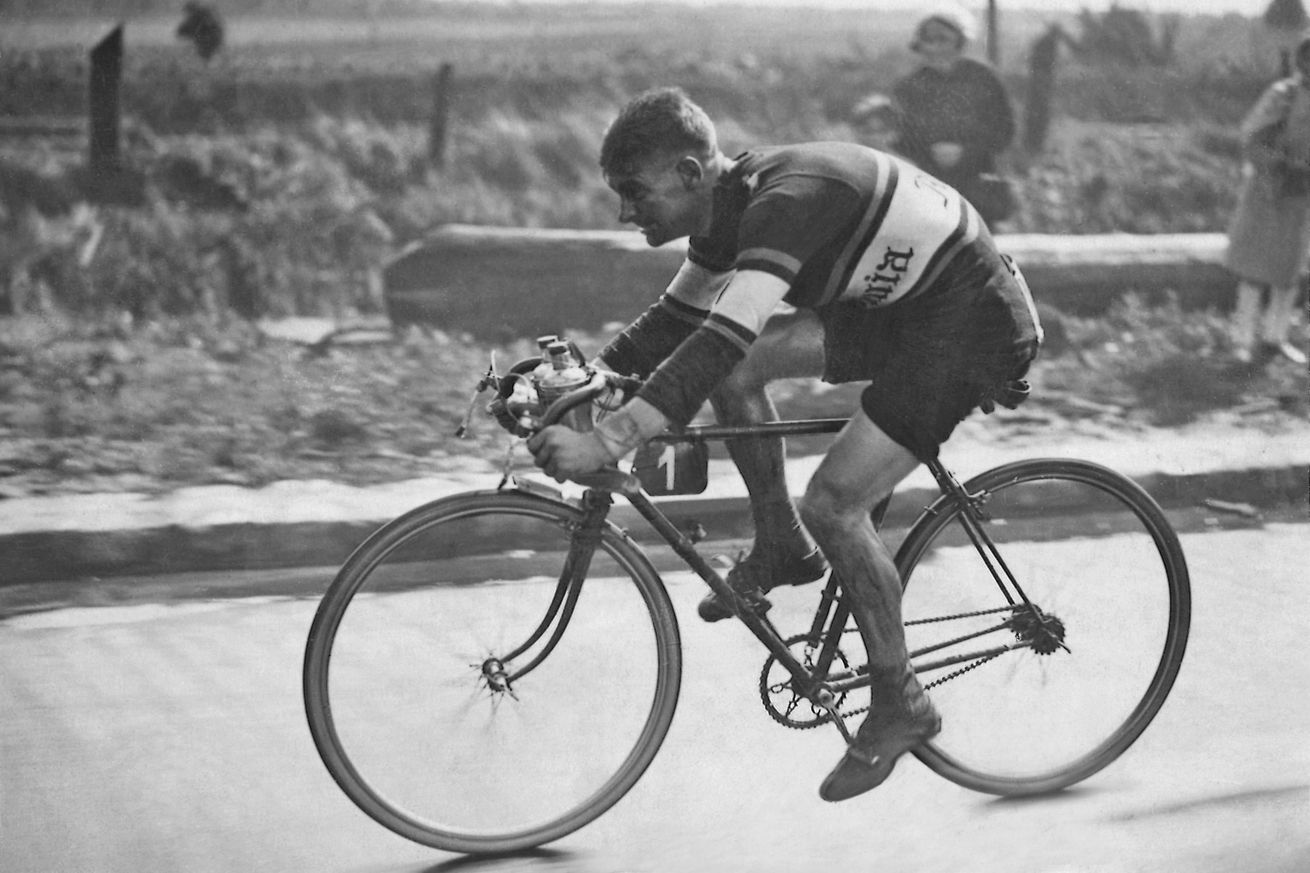

Hubert Opperman at this stage in his career was a hero of Australian cycling and a two-time veteran and of the Tour de France – where he had become a fan favourite – as well as winner of another forgotten Classic, the Bol d’Or, a twenty-four hour tandem-paced race on the cement track of the Vélodrome Buffalo, contested by some of the best roadmen of their era. Its roll of honour includes names such as Gaston Rivierre, Lucien Petit-Breton, Réne Pottier, Léon Georget, Oscar Egg, Honoré Barthélémy. And, in 1928, the last year it was run before a long hiatus, Opperman had added his name to that list.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11726435/0010_TdF_1928.jpg) Courtesy of Melbourne Books

Courtesy of Melbourne Books

When invited to ride Paris-Brest-Paris in 1931, Opperman was given the number one dossard. That wasn’t just a factor of his popularity, though that undoubtedly helped. His Bol d’Or victory singled him out as a serious contender for the twelve-hundred kilometre PBP, where the best time to-date had been set in 1911, fifty hours and thirteen minutes. As did the place-to-place and endurance records he had been setting in Australia since his return from the Tour in 1928, most notably Sydney-Melbourne (940 kms). Those records were where Opperman found his métier:

“At heart he was a soloist, an endurance time-triallist, perhaps the best in the world. Although the Paris-Brest-Paris event required teamwork and good race tactics, its unique requirement of two nights without sleep elevated the importance of the individual rider’s mental toughness. Many top cyclists possessed a similar athletic capacity to Opperman. But few possessed the appetite for suffering that fifty hours of non-stop racing demanded.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11726437/0100_Le_Petit_Journal.jpg)

The first half of the race was contested in atrocious weather, a thunderstorm buffeting the peloton as it raced toward France’s westernmost port. Attack and counter attack were the order of the day, all coming to naught except to winnow the peloton. The main contenders were still together as they raced into the second tunnel of night:

“I was wretched with fatigue ... For hours I fought against the insidious onset of sleep. I whistled. I shouted. I strove to think of anything so that Morpheus would not clutch me too fiercely … It was agony.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11726441/0110_PBP_020_Dreux_Joly_Bonduel.JPEG) Gallica/BnF

Gallica/BnF

Come daylight, the City of Lights was two hundred kilometres away and five riders were out in front: Frantz, De Waele, Bidot, Pancera, and Opperman. The four European riders knew one and other well and were as used to riding with one and other as against. They were also used to making deals with one and other. And they had struck a deal to deny Opperman the chance of victory. “I was like a lost sheep among the wolves,” the Australian wrote in Le Miroir des Sports after the race, his rivals ganging up in an effort to do him over. Each attacked and it was left to Opperman to bring him back, only for a new attack to be launched. Then Opperman found his moment. Bidot attacked. Opperman chased. The Frenchman punctured. Opperman pushed on. Frantz bridged across and brought De Waele with him:

“Then, on a low hill, Opperman launched his most ferocious attack, throwing everything he had into the pedals and taking advantage of his light climber’s physique. At last, he had shaken them. He now faced a fifty-six kilometre solo pursuit to the finish. Opperman built a three-minute lead. But behind him came the pack, which had grown to include Léon Louyet [...]. The five riders, each champions in their own right, combined forces to erode Opperman’s lead, which soon dropped to two minutes. [Bruce] Small [Opperman’s directeur sportif] screamed from the car: ‘Oppy, ride like the devil!’ Over the next hour, the group reduced Opperman’s lead to just thirty seconds. Nineteen kilometres remained.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11726443/0120_PBP_050_Opperman.JPEG) Gallica/BnF

Gallica/BnF

Five kilos out, it was all for nothing, the chasers sweeping up the Australian. As twelve hundred kilometres of furious racing wound down to zero, a quintet of riders approached the Vélodrome Buffalo: Émile Decroix and Léon Louyet, both riding in the colours of Génial-Lucifer; Marcel Bidot, Alcyon’s sole remaining representative in the lead group, Maurice De Waele and Nicholas Frantz having slipped back; Opperman, in his Alléluia jersey; and Giuseppe Pancera.

“They rode over a stretch of cobblestones, down a muddy ramp and through a tunnel that led to the concrete track of the arena. Bidot led the exhausted troupe into the arena and made a furious surge with the aim of soloing to the finish. Unable to sustain the effort, the four pursuers quickly brought Bidot to heel. The lap bell sounded. De Waele was the first to move. He led out, followed by Louyet. Pancera swept around them and moved high up the banked slope of the track. Opperman followed. Two hundred metres from the line, Opperman unwound his sprint. He flew from Pancera’s wheel, charging down the slope with enough momentum to pull to the front. Opperman tore across the line, narrowly missing a group of spectators who had rushed onto the track. He had won. Forty thousand spectators suddenly transformed into ‘a mob of yelling lunatics.’”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11726445/0130_PBP_090_Bidot_Louyet_Opperman.JPEG) Gallica/BnF

Gallica/BnF

It would be wrong to say that few remember Hubert Opperman today, his 1928 Tour de France having achieved a kind of lasting fame. Phil Keoghan’s Le Ride sought to recreate the events of 1928 eighty-five years on. David Coventry’s The Invisible Mile used the race as a vehicle to explore René Girard’s ideas on mimetic desire. Mostly, though, Opperman is reduced to that one race, even by those aware of his other cycling achievements and of his post-cycling career in politics.

Daniel Oakman opens Opperman’s story out, taking the reader through the different phases of his life. As well as the stories of his two Tours de France – after 1928 he returned to the race in 1931, as part of a mixed Swiss-Australian team that included future Year record holder Ossie Nicholson – Oakman covers the important Bol d’Or and Paris-Brest-Paris victories, as well as other road races both in Europe and Australia. Many of Opperman’s major place-to-place and endurance records are covered, most notably his Land’s End to John o’Groats ride and his Freemantle to Sydney transcontinental ride.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11726461/0200_The_Ravat_Wonder_Boys.jpg) Courtesy of Melbourne Books

Courtesy of Melbourne Books

Oakman also tells the story of Opperman’s eighteen years as Liberal Party member for Corio, and his two stints in the cabinet, as minister for transport and shipping and then as immigration minister, the years in the latter ministry resonating today, immigration once more to the fore in national and international politics. There’s also his post-politics career as a diplomat, Australia’s high commissioner to Malta.

Through all of this we get a picture of a man who won people over with ease. His dogged determination against the odds won admiration, his charisma off the bike won hearts. Much of the latter had been honed in Australia, where he’d been a front man – brand ambassador – for Malvern Cycles, touring the country and talking about cycling in theatres and town halls.

Beneath the surface, though, there was another side to the man, one rarely seen in public:

“Ambition and humility are unlikely bedfellows. Although Opperman was essentially a modest man and he publicly demurred when people spoke of him as one of the greatest cyclists in the world, he struggled to cope with criticism. For all his apparent toughness, he could be surprisingly insecure. He still bridled at the suggestion that his preparations and planning for his big records were too elaborate, too commercial, too controlled, or too theatrical to be real measures of sporting achievement. He paid attention to those same rivals who said he was only an ‘unpaced plodder’ and afraid to race, not because he disliked the handicap system, but because he feared events over which he had limited control. In some ways, they spoke more loudly to him than nearly two decades of breathless praise from the nation. These were the whispers that drove him on. He rode on fury.”

The insecurity wasn’t really be a surprise, Opperman having had a somewhat peripatetic childhood, farmed out among relatives:

“Materially the Opperman children may have been poor, but they were warm and well-fed. Their emotional needs received less attention. As a child Hubert suspected that his father often forgot all about him. Dolph and Bertha were not unloving, he believed, but there were ‘no great demonstrations of affection’. In turn, Hubert’s regular absences from his family may have contributed to this lack of intimacy or closeness. His devotion to his father, however, was unconditional.”

The effects of such an upbringing can be seen throughout Opperman’s life. In the father figures he was drawn to, such as Malvern Star owner Bruce Small or the Liberal leader Robert Menzies. In the way Opperman could put the needs of others ahead of his own beliefs, such as in his work to reform the White Australia Policy despite his own contempt for the notion of multiculturalism. You could probably even attribute Opperman’s charisma to that childhood, his attempts to win the affection of his father, and others, ingraining in him the skills necessary to win others over.

While all of this is in Oppy, while Oakman brings these issues and more to the surface, the nature of sporting and political biographies means that Opperman himself – the man behind the myth – doesn’t really get much of a chance to show himself. We get told about about his charisma without ever really seeing it for ourselves. We can see that it can’t be doubted – look to the way the French fell in love with him or look to the way Australians fell in love with him – but I’m not sure if we ever get to see it with our own eyes. And Oakman’s telling of the story – the ease with which he condenses the sporting and political career without appearing to skimp on detail – does make you want to taste that charisma for yourself.

Near the end of the third act of his career, the diplomat’s years, Opperman received a letter from an old rival, Giuseppe Pancera, the man whose wheel he launched himself off to win Paris-Brest-Paris nearly four decades before:

“Do you remember our famous legs and our youthful vigour whilst cycling? After having cycled for miles and miles of kilometres, the admiration of beautiful ladies who wanted to possess a handsome athlete? Setting humanity on fire with our beautiful sport?”

Opperman was to the fore in Australia in establishing cycling’s place in the popular imagination and he played an important role in dragging European cycling into a new era. He rode in an age when the vagabonds of the road who had given life to the Tour and crafted its first era of legends finally usurped the aristocrats of the track, the years in which the prisoners of the road became the true kings of the pedal. With Oppy, Daniel Oakman affords us a chance not just to understand the man, but to gain new understanding of an era of cycling that still resonates today, as we divide our attentions between the hyperreality of the top end of the sport and the growing appeal of modern soloists riding transcontinental or challenging place-to-place records that once bore Opperman’s name. With Oppy, Daniel Oakman affords us a chance to remember what we never knew, to live again a time when cycling had the power to set humanity on fire.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11726463/0001___cover.jpg)