Rock Therapy: How Climbing Saved Cedar Wright and Lucho Rivera From Their Downward Spirals

The rope arches in an unbroken loop from me to Lucho, 30 feet above. “At least there’s no rope drag,” I quip, trying to make light of his predicament. We are six pitches up the South Dragon’s Horn on Tioman Island, off the coast of Malaysia, living proof that climbing can go from fun to fubar in a microsecond.

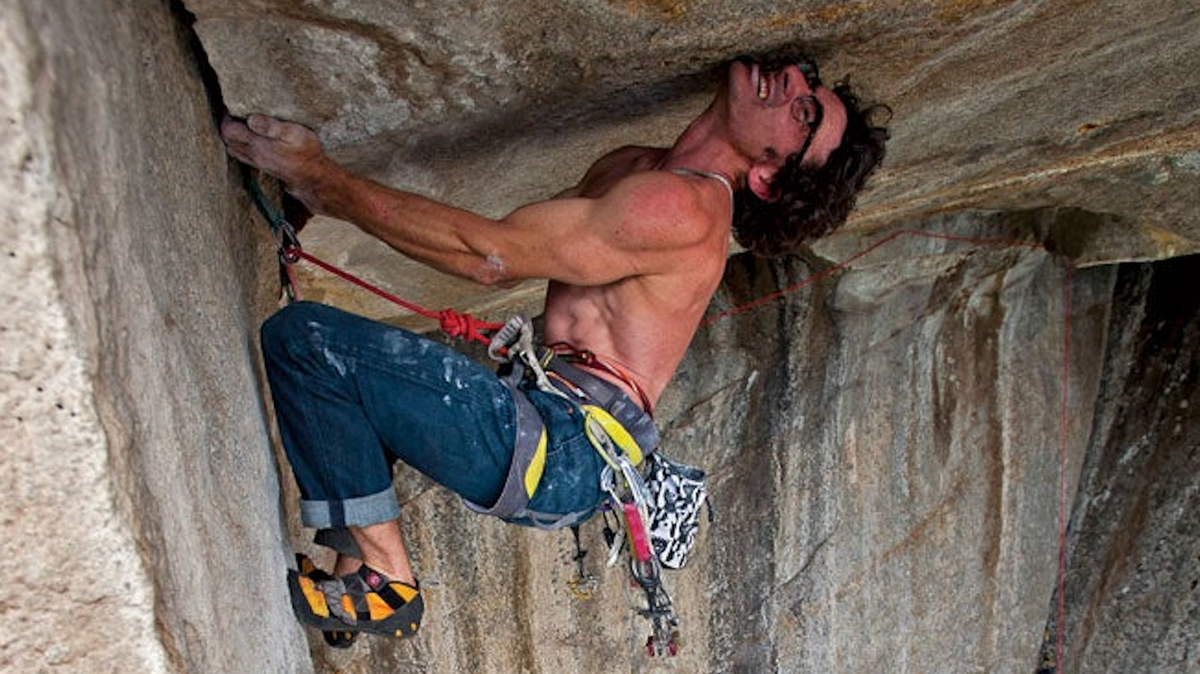

A moment ago, we’d given knuckles at the anchor, raving about another classic pitch as we enjoyed a view of the jungle and the South China Sea below. Now, the good times are on hold. With accelerating gasps and groans, Lucho weasels in a small RP behind a suspect flake. He hurriedly clips a draw to it, gives it a tug, and promptly rips it right out.

He dances his fingers and toes back and forth on small nubbins, trying to devise a plan that doesn’t end with broken legs.

“Can you get a hook?” I ask.

“I don’t know, man…” Lucho’s voice quavers as he hunts his harness for the hooks.

“You’ve got this, man,” I say in a fairly less-than-convinced tone.

Lucho shouldn’t be up here. Not because this particular situation is dangerous—although it is—but because it’s a small miracle that he isn’t dead or in prison. Lucho grew up in a rough neighborhood in the concrete jungle of the Mission District in San Francisco, and by age 11 had joined a gang. “We’d hang out in the local park at night, walk up and down 24th Street, and try to control what people were walking around the block. If they were wearing blue, they’d get approached.”

The reality of Lucho’s life path became clear when he was about 16. He had gone with his crew to face off against a rival gang. “Everyone was talking shit, with bats and pipes, when the littlest dude of the bunch pulls out this Dirty Harry pistol and starts shooting. We all just started running. One dude got hit in the back. We dragged him into our car and blew every red light to the hospital. That was the moment where I was like, ‘This is fucked!’”

Lucho is just a stone’s throw above me, yet there’s nothing I can do for him but say, “Breathe. Relax.” He places a teetering hook on the hollow flake and slowly weights it. Ping! The hook pops off, slapping his chest, and Lucho’s body arches under the force. I can hear the scratch of his fingernails against granite as he puts the death grip on a micro-crimper. “Ahhhhh!” Lucho and I both scream in unison.

I really shouldn’t be here, either. When I was young, things were fine— great, in fact. While Lucho was a young gangster patrolling his block, I was happily bushwhacking across my family’s 11- acre northern California “hippie ranch.” I played in the dirt and climbed to the top of the huge trees that peppered our property. I was a lucky, happy kid. But somewhere along the pathway to adulthood, I got lost.

In high school, I buddied up to the cool kids, who reluctantly allowed me to hang around, though I felt more comfortable reading comics and playing Dungeons and Dragons with the geeks in the library. I was caught between worlds: too cool for one club and not cool enough for the other. I had no rudder, and I drifted to drugs.

I still vividly recall one low point: A mysterious smoke filled my 17-year-old lungs. For a moment I was indestructible; then I was a ghost. I watched my body fall backward into the street. My head made a loud thwackkk as it bounced off the blacktop. From a fetal position I could see my “friends” looming, laughing with distorted, clown-like grins, pointing their melting fingers as I convulsed on the ground.

I awoke to the sound of a car horn, and sat up face-to-face with blinding headlights. “Get the fuck out of the road, you idiot!” A middle finger popped out the window of the pickup as it careened past.

After high school, things got worse. Without my geek friends to bring me back to Earth, I floated away completely. For college, I chose the beautiful brick campus of Chico State—for its reputation as the “best party college in the world.” There was not a night that you couldn’t find a party on one block or another. I remember one evening watching a mob of drunken partygoers tip a car up on its side. This was not an isolated event. I became more morose and isolated. Somehow I managed to maintain a decent GPA, but I was an emotional mess. One morning I woke up covered in vomit in a ditch outside a frat house with no idea how I got there.

I didn’t have friends, just people I got high with, and pretty soon I was the go-to guy for a hookup. Acid, weed, ’shrooms— what do you need? By the first semester of my second year, the Feds were digging in my dumpster, and my breakfast came out of a blotter. After a particularly bad trip that left me bedridden for several days, I slipped into a dangerous depression. It’s amazing what we can recover from.

Having hit rock bottom in Chico, I managed to start a slow climb out of the darkness. I cleaned up my act, quit everything, even coffee, and transferred to Humboldt State. Walking Moonstone Beach one day, out on the mythical Lost Coast, I saw climbers dangling from the beach cliffs. “That looks badass,” I thought.

From my first climb, I was hooked. I spent my money on ropes and gear instead of bags and bongs. I climbed every day. When I burned through climbing shoes, I’d climb barefoot. I climbed in the blazing sun, and I climbed in the rain.

Soon after, I met the hardman Sean Leary, and I received a sandbag crash course in runouts, free soloing, and bolting from hooks. “Yeah, dude,” Sean said, “last summer I stayed in Yosemite for three months, and spent less than two hundred dollars.” I hurried toward graduation with my head full of dirtbag dreams. Screw getting a “real job.” I would live in my car, in places like Joshua Tree and Yosemite, and climb full-time on a shoestring budget.

For the little bit of cash I needed, I began working as an outdoor educator, sharing the passion that had saved my life. And why not? I was living proof that life on the rock was powerful therapy. I recognized myself in many of the kids: the insecurity, the aimlessness, the hidden potential. And I saw it work: The physical exercise, the teamwork, the beauty, and the separation from the influences of their daily life worked their magic on at least a few kids every trip.

I pushed through the grades and honed my crack climbing skills, in J-Tree in winter and Yosemite spring, summer, and fall. By my third year of full-time dirtbagging, I moved from outdoor educator to a spot on Yosemite Search and Rescue. I rubbed shoulders with the likes of the Huber brothers, Dean Potter, and Leo Houlding. In my eyes, these athletes were truly living the dream, a dream that soon became my own: to become a jet-set sponsored rock climber. A few speed-climbing exploits with Ammon McNeely and Chris McNamara put my foot in the door, and with a bit of luck and unadulterated desire, I started to pick up my first sponsors.

I brace for Lucho’s factor-two deathwhipper onto our anchor, but his survival instinct outguns the laws of physics, and somehow he stays on the rock. Spasmodically, he pushes the hook far above his head. It latches something unseen. Lucho eases, hyperventilating and wide-eyed, onto the blind placement.

“Are you sure that hook is good?” I call up nervously to Lucho.

“Don’t know man; want me to bounce-test it?” he snaps sarcastically, before delicately tapping at the hand drill.

A half hour later he slumps with infinite relief onto a bolt. “Dude, that was hella cool,” he boasts, his gangster bravado back. “We’re going to summit!”

By Lucho’s junior year in high school, he was rarely in class and facing expulsion. A school counselor suggested a program called Urban Pioneers, which gave kids school credits for a mix of classes and wilderness experience. Lucho was dubious, but felt he had no other option than a dead-end on the street.

Soon after joining, he was taken on a two-week backpacking trip into the Sierra. “I didn’t even know there was that much land,” he says. “I wanted to know what was on the other side of each ridge. Every day on the trip, when we got in to camp, I wanted to explore.” For the first time in his life, Lucho saw the Milky Way.

“At the start, there were kids from rivals gangs sporting their rags on the trail, and by the end of the trip they were homies,” Lucho says. “You had to stick together. Everyone had some piece of equipment that we needed for the trip to function.” On top of that, the instructors seemed to genuinely care. “I remember thinking that I’d never had a teacher like this who seemed to really give a shit about our lives.”

After that outing, Lucho and a couple friends from the trip returned several times to explore further into the Sierra. The small posse of ex-gangsters was quite the sight. One minute they’d brag how “hella easy” the hike was, and the next they’d be terrified, banging pots and pans to scare off a bear. The world had expanded for Lucho, and he was getting the same good tidings from the mountains that John Muir had gotten when he ventured out of the Bay and into the Sierra so many years before.

But Lucho’s old life haunted him. When he approached his gang leader about getting out, he got a chilling answer: “Blood in, blood out.” Translation: The only way you are leaving is dead. Lucho discretely tapered off his gang activities, and finally the crew approached him.

“I thought I was going to get shot,” Lucho says, “but they just told me I had to fight this guy.” The dude had been one of Lucho’s best friends in the gang. But Lucho just wanted to be free. All that desperation came out in a flurry of fists. “I kicked the shit out of him,” says Lucho. “Then he got up, shook my hand, and the rest of the guys were like, ‘It’s squashed.’”

Unlike most of his friends, Lucho graduated from high school. He got a job at The North Face Outlet in Berkeley. Several of the employees were climbers, and they gave Lucho his first taste of rock, on Bay Area crags. “One day they invited me to Yosemite to climb Higher Cathedral Spire.” The expedition turned into an epic, with off-route variations, slab whippers, dropped gear, and dehydration, but they summited, and the seed was planted.

But Lucho’s true turning point came at a slideshow at The North Face store. Jim Bridwell told tales of Yosemite first ascents, and Lucho thought, “Who is this crusty-ass old guy? He has done some badass shit.”

After the show, Lucho raised his hand and urgently asked Bridwell how he managed to defy the regulations and live in Yosemite full-time.

“I don’t know, kid,” Bridwell said. “We just did. We’d sleep behind boulders, move around a lot. We just stayed.” Soon after, Lucho went to Yosemite… and stayed.

The arcs of my life and Lucho’s soon merged. I met him in the parking lot of Camp 4 three weeks after Bridwell inspired him to quit his job and move into his truck in the Valley. I was now a fairly seasoned Valley local, working on YOSAR. Though Lucho was a wide-eyed newbie, I was looking for someone—anyone—to help me out on my Gravity Ceiling project, a huge roof I wanted to free climb, many pitches up, near the top of Higher Cathedral Rock. I heard Lucho might be game.

Lucho’s learning curve was dramatic. In the year I met him, he went from epics on 5.9 to sending 5.12. Clocking one off the-beaten-path first ascent after the next, we started to get the reputation of being “choss masters.” Admittedly, not every FA was a gem, and some might be considered true suffer-fests, but our tortured pasts helped us find fun where others wouldn’t.

Years slipped by, and those times climbing in the Valley with Lucho started to seem like “the good ol’ days.” Each year I sojourned back to Yosemite, but also branched out to more exotic adventures. I established new routes around the world, fell in love, became a writer and filmmaker, and basically woke up feeling like a lucky bastard every day.

Lucho, meanwhile, continued to live the dirtbag dream, hanging tough in Yosemite, free climbing El Capitan, putting up obscure new routes, and only working as much as he absolutely had to. We kept in touch, and I think we were both a little envious of each other. “Dude, when are you going to get me on one of these sponsored trips?” he asked one day over the phone. “Don’t worry Lucho, I’ve got your back, man,” I promised him. “One of these days, I’ll hook a brother up.”

Fast-forward to 2011. An old college friend from Humboldt, Bennett Barthelemy, invited me to participate in a Big City Mountaineers fund-raising program called Summit for Someone. Big City Mountaineers’ mission was close to my heart: “to mentor under-resourced urban teens through transformative outdoor experiences,” and Summit for Someone was a program they ran to help good-hearted adventurers raise money for their cause. Bennett and I planned to put together a custom trip, using our industry connections and media savvy to raise a nice chunk of cash.

Bennett suggested an unusual objective: a pair of huge granite spires called the Dragon’s Horns, on Malaysia’s Tioman Island. He sent me a video link, and I realized that I’d actually heard about these obscure spires. My buddy Scotty Nelson had made the first ascent of the south tower. “It is definitely the coolest thing I have ever climbed,” I remembered him saying.

The project quickly built momentum. The North Face generously offered to match the first $5,000 we could raise. But then, last minute, Bennett had to back out. I scrambled to find a replacement.

I thought of Lucho. He had just finished a proud 5.13 first ascent on the Sierra’s Incredible Hulk. He was in the best shape of his life—psyched, but broke. With my end of the trip fully funded, I figured we could work that out. Lucho had never been overseas. I couldn’t help but feel like it was karmic: Lucho and I teaming up for our biggest first ascent, out in a jungle wilderness, raising cash to help troubled kids like the ones we used to be.

Our arrival on Tioman Island was surreal and abrupt. After three days of travel by plane, bus, ferry, and fishing boat, we dropped our bags at our rented bungalow, threw together some gear, and, in a jetlagged haze, hiked through the jungle toward the North Dragon’s Horn.

While details were sketchy, our Google/ Supertopo/American Alpine Journal search had revealed that the easier to reach South Horn had been climbed several times, but the North Horn was apparently a virgin summit. On the plane we had decided we’d first attempt the virgin north summit by the proudest line we could find, and then try to establish a new free route on the South Horn.

The jungle felt… pissed off. Every plant had a thorn on it, and we were thankful for our leather gloves. Huge ants swarmed everywhere. Some mystery bug was emitting a continuous, deafening shriek like a car alarm. I was immediately on edge.

During our journey to Malaysia, Lucho, the ex–street thug, had confessed that he was deeply afraid of snakes. And bugs. “Might be a problem, Lucho,” I warned. He had not been exaggerating. At every turn, he screamed and jumped at some real or imaginary critter. For me, the humidity and heat were the bigger battle. Sweat stung my eyes. My glasses fogged up. It was like hiking in a sauna.

Even though we’d packed our climbing gear, we assumed this would be a recon mission. But a few hours later, covered in scratches that were stinging from sweat, we found the steep granite of the North Dragon’s Horn suddenly looming above us. We could see huge sea birds playing in the thermals far above. Realizing we might actually get to climb, I was overcome by summit fever and began forging ahead through the jungle.

Suddenly, something that sounded like a hummingbird buzzed by my ear. More buzzing ensued, and then I felt a sharp, stabbing pain in my side, then another in my leg. I scrambled madly through the vegetation, reduced to a frantic, screaming kid. I reached back to a burning spot on my shoulder and snagged a huge, writhing object between my fingers. What I saw didn’t compute. It was a hornet, but larger than my thumb, with wild orange stripes across its pulsating abdomen. It squirmed as it tried to maneuver its stinger for another attack.

Thirty yards of frantic thrashing later, vibrating and hyperventilating, I was out of the swarm. A mix of poison and adrenaline surged through my body. Lucho had screamed and run in the opposite direction, beating a long retreat into the jungle. “You all right, man?” he yelled. Between us, dozens of pissed off mega-wasps divebombed their territory. “I think I’m OK,” I replied. I lifted my shirt to reveal a huge red-and-blue welt. Every gangster bone in Lucho’s body had evaporated, and it was only with my extreme coaxing, that he half-trembled, half-squealed his way in a wide arc around the swarm zone.

By the time he met me at the base of the tower, Lucho had recovered his bravado: “Dude, we got this shit fo sho.” I found his cocky outbursts equal parts hilarious and helpful in attacking the unknown.

Once we roped up, one pleasant surprise followed the next. The rock was bulletproof granite, with wild flake, knob, and pocket features, plus incipient cracks for protection.

As long as you didn’t mind 50-foot runouts and the occasional grass-hummock mantel, it was classic climbing. I tried to ignore the throbbing pains that were radiating from the stings while Lucho stretched out a sixth pitch and set up a belay under an overhang just as a bone-shaking crack of thunder announced a sudden downpour. The rain actually offered respite from the heat, and the stone was gritty enough to climb when wet. I found Lucho soaked but psyched at the belay.

As quickly as the rain had come, it went, and by the time I led the seventh pitch the sun had dried me out. My hornet stings began to throb as I belayed Lucho up. Then the clouds blew back in while Lucho led the eighth, and crux, pitch, with a hard 5.10 traverse 40 feet above protection. Wild cloud-to-cloud lightning began to flash around us, and another downpour hit as I started following the pitch. Was it possible to get struck by cloud lightning? By the time I reached the crux, a waterfall covered it. Facing a nasty pendulum, I held my breath, submerged, and somehow stuck to the crimpers that led to the other side of the cascade.

Past the hardest climbing now, we simul-climbed to the end of the rock. The rain subsided, and another few hundred feet of bushwhacking took us to the summit. Three days after leaving the States, we were the first documented humans on top of Tioman’s North Dragon’s Horn.

We climbed a spindly tree to get a view. The swirling clouds were on fire with oranges and reds, and we could see far into the interior of the island, where more wild towers protruded from green ridges, too far into the jungle to probably ever be climbed.

The idea of rappelling at night into the hornet-ridden jungle seemed less than awesome, so we open bivied on the summit. We awoke in the middle of the night and noticed that our bed of leaves was glowing, covered in a phosphorescent mold.

At around two in the morning, a new display of lightning convinced us to head down. All I could think about was hornets. But we made it down the wall and through the jungle without incident, and retired to our bungalow on the beach to enjoy a couple of rest days. I managed to get online and was happy to see that we’d already raised nearly $7,000 for Big City Mountaineers.

After completing the North Horn, we began scoping the south tower from various angles, consulting our notes to figure out where the three existing routes went. Eventually we realized that arguably the most beautiful line, an impressive Nose-like buttress, was unclimbed.

After three days of work, using fixed ropes to regain our high point each day, we were nearing the top on our South Horn dream route when Lucho ripped his hook and yet somehow managed to stay on the rock.

“Dude!” he said from the comfort of his newly placed bolt. “We’re going to the summit for sure. Hella cool,” he said, as he continued up the pitch.

A few days later we completed our new route to the top. During our forays we had freed every pitch, but the in-a-push free ascent remained. The monsoon was now upon us, and the weather socked in for several days. Lucho made earnest prayers to the mountain to allow us one last moment of passage.

Just before a month of nonstop fog and rain, we were granted a five-hour window of dry-ish weather, allowing us, just barely, to complete a free climb to the summit. We stood smiling on top of Tioman Island, looking out over the South China Sea, with a mass of clouds and lightning quickly approaching.

We let it all sink in: the surreal setting, the incredible climbs we had established, the many mishaps and mistakes in our pasts—all had somehow led to this moment. As we’d both experienced years earlier, there is nothing more transformative than colliding with nature on its own terms. Complications of modern life fade away. We are revealed to be fragile animals, in a beautiful and mysterious landscape. Climbing is dangerous, but for Lucho and me the alternative was infinitely more perilous. Climbing had saved our lives. A hard day out followed by a night under the Milky Way was our therapy.

“Dude, thank you so much for bringing me here,” Lucho said, with tears in his gangster eyes.

“It’s kind of a miracle we are here, huh?” I replied.

Cedar and Lucho raised nearly $10,000 to support Big City Mountaineers. Learn about Summit for Someone fund-raising expeditions and the Big City Mountaineers programs for urban teenagers at summitforsomeone.org.

The post Rock Therapy: How Climbing Saved Cedar Wright and Lucho Rivera From Their Downward Spirals appeared first on Climbing.