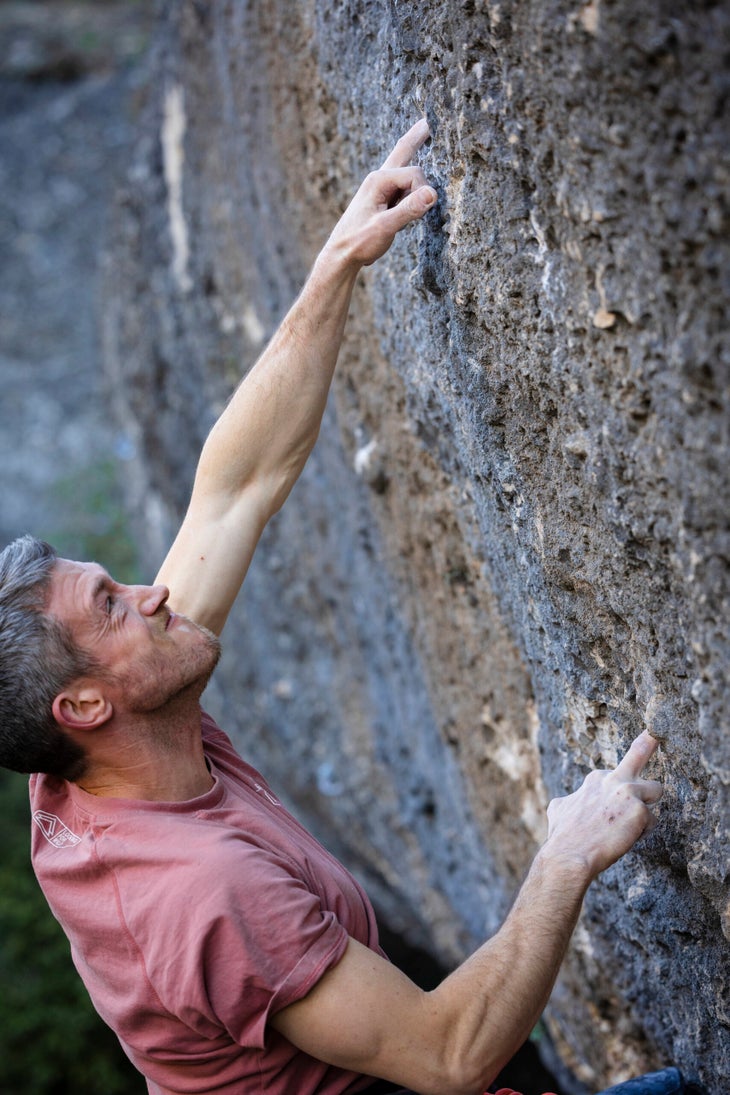

Tom Bolger Shows How to Make Pro Climbing Work

Tom Bolger is a lot of things. He’s a professional climber who’s supported by Tenaya, Fixe, and Looking For Wild. He’s also a YouTube-trained home renovator, a homestay host, and a rope access professional. Though he’s English by birth, he spends every spare moment climbing and bolting near his adopted home in Northern Spain. He’s sent 5.15b. He can do one-arm pullups on the Beastmaker 2000’s 25-mm mono pockets. He’s spent years of his life working (and sneaking fingerboard sessions) on rusty oil rigs in the middle of the North Sea.

Ever since the age of 8, when Bolger and his father began having “proper adventures” with a secondhand trad rack on the techy gritstone near Leeds, England, Bolger has had a “make it work” approach to the climbing life.

When Bolger finished school at 18, he moved to Sheffield, the center of the UK climbing world, and leveraged his climbing skills to get a rope-access gig. He’d do a two- or three-week stint offshore, then flee with his earnings across the English channel to sport climb in France. This worked for a while. But when he made his first trip to Catalonia, Spain, he was awestruck by the scale and quality of the climbing and decided to establish his life there.

He saved his money, doing “a good long stint” of back-to-back rope access shifts, then quit and moved to Catalonia, where he took a job teaching English, something he had “absolutely no idea how to do.”

“I didn’t speak Spanish,” he said, “and I didn’t know how to teach, but I was like, Well, this is my opportunity to live here, so I just winged it and taught everyone dodgy English for a while.”

But even though he was living near the rocks, and even though he was embraced by the “massively accepting” Catalan and Spanish climbing communities, he quickly learned that teaching wasn’t nearly as conducive to climbing as he’d originally hoped. “I was at it six days a week,” he recalls. “I didn’t have any free time.”

After some deliberation, Bolger decided to re-invest in his rope access skills and begin rotating between very different lives: He’d spend three weeks climbing full time, sending projects, bolting new ones, and training the maniacal pocket strength he’s now famous for; then he’d pack a bag, board a plane, and fly out into the North Sea for two- or three-week shifts, supplementing each day’s work with some fingerboarding and core to minimize the losses incurred by the time off the wall.

The schedule worked pretty well from a free time perspective, he says, but wasn’t ideal for performance. It was hard to train well on the rigs, and the three weeks he had off almost exactly matched the time it took for him to get back to top form—but by then he’d be packing his bags again. Still, it was better than teaching, and as the years passed, he settled into the routine, became a respected local route developer, leveled gradually up through the grades, and, to his surprise, found himself able to supplement his rope access income with sponsor support.

Eventually, this support became large enough that, when combined with the homestays he’d renovated and rents out on Airbnb, he was able to decrease the frequency of his trips north and further double down on what, from the outside, looks like the carefree life of a full-time, professional climber.

Since I’ve been trying to figure out what being a pro climber actually means in this day and age, I called him up.

Bolger, now 36, has a soft and thoughtful voice. We spoke by WhatsApp on a Friday last month. It was 9 p.m. in Spain, and Bolger had spent the day at a small crag he’s helped develop near his home. “I reckon I spent about half my free time climbing,” he told me, “and half my free time bolting. I’m pretty much out there all the time.”

Some of these climbs, like Pink Panatas, a 5.15a first sent by Alex Megos, and E.L.L.I.E,* a 5.15b that Bolger himself recently finished, are world-class hard. But he bolts routes across the difficulty spectrum. Hours before we spoke, he’d clipped the chains on a new moderate before a spring storm rolled in. As we chatted about what it means to be “a professional climber,” about how he went from a gritstone climber to a mono-pocket fiend, and about his process on E.L.L.I.E., I could hear thunder booming in the background and water hammering on the roof.

*The name is both the name of his dog and an acronym for Every Lesson Learned Is Evolution—something that describes his multi-season, multi-injury process on the climb.

Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

THE INTERVIEW

Climbing: I feel like there’s a lot of confusion about what the term “pro” means in a climbing context these days. A lot of people seem to think that if they climb a certain grade, it’ll make them a pro, so they work hard at their climbing and eventually accomplish that grade, but then they’re disappointed because it doesn’t just change their life. Part of me wants to correct that assumption among aspiring pro climbers—that climbing a V16 or 5.15b means that climbing is magically going to work for you in a financial way—since most “pro” climbers seem to make climbing work by doing other things that both generate income and increase their value to sponsors. They’re heavily engaged in YouTube and Instagram, for instance, or they host podcasts and publish niche magazines, or they coach other climbers, or they do a bit of all that while also hanging commercial Christmas lights or coding on the side. In other words, they have side hustles. That seems like something you know a thing or two about.

Bolger: Yeah, I’ve seen a lot of really frustrated climbers over the years, some of whom end up almost quitting, because they want being a pro to be something that it isn’t. And that disappointment has always existed. People have thought that if they climbed a certain thing, or reached a certain grade, there’d instantly be life-changing calls from sponsors. Sure, you’ve got to pull hard and climb hard, but setting up your lifestyle so you can actually do that for a long time is as important, if not more so. For me, being a professional is about doing what it takes to create that lifestyle for yourself. If your mindset is based around becoming a pro climber rather than just becoming someone who has time to climb a lot—well then your attitude is geared in the wrong direction. Someone who just wants to climb, and who wants to do the most that they possibly can with their climbing, will be willing to do all that other stuff to make it work. And you can do that regardless of what level you climb. I’ve got friends who are just so psyched—the most psyched people I know—who’ve created lifestyles so that they can climb as much as possible. They’re not pro climbers, but they climb a lot. So I think the make-it-work mentality is super important.

I think I’ve also been lucky in that I’ve never had the assumption that a certain climb was going to make it or break it for me. I never thought it would really happen. So I always hedged my bets by making other things work and not relying on sponsors. I also didn’t want climbing to necessarily be my career. It’s my thing. I didn’t want to ruin it or spoil it or turn it into a job. I wanted to keep it as pure as possible.

Climbing: It’s the thing you want to do the moment you get back from the North Sea.

Bolger: Absolutely!

Climbing: Let’s talk about that. What does life look like on an oil rig in the North Sea?

Bolger: The rigs are basically huge rust buckets; they’ve been there for a long time; so it’s all maintenance work for the structures and the pipeworks. The most recent one was industrial painting, which involves sandblasting the metal structures. I do the work, but I am also the supervisor in charge of rescues, setting up the rope systems so that if anyone needs to be rescued it’s all settled up front in a safe way. It’s pretty wild out there.

Climbing: Did you ever figure out a good training method?

Bolger: I found a couple of things that work well for me. They have very small gyms, so I’d take a fingerboard out there. The big thing for me is to keep some level of consistency. You’ve got to be psyched enough to maintain a certain level of fitness so that when you come back you aren’t spending your entire off period trying to get back in shape.

Climbing: You’re not doing rig work as much as you used to, right?

Bolger: I did it steadily for a long time, many years, but eventually I made a conscious decision to prioritize climbing. I had a permanent slot on the rigs, and I was getting paid well, working two weeks on, three weeks off. And it’s hard to get those permanent slots, there’s not that many of them. But I felt like I couldn’t give my all to climbing, so I gave up the permanent slot, and sponsors gave me a bit more, and I was able to start renovating some houses and renting them out to climbers on Airbnb—which is something I wanted to start doing years ago but had to save the cash to do. It’s worked out. But I still do rope access trips to supplement.

Climbing: How’s the Airbnb thing been?

Bolger: It works. But it’s definitely tougher than people seem to think. It only works if you buy something cheap and renovate it yourself so you’re saving a lot on the labor and construction. That’s what I’ve been able to do. But if you buy something that’s already ready to rent, the margins just aren’t that good. I think people overestimate how much these properties generate. And it’s all about the location. Margalef, Montsant, Siurana—they’re good places to visit as a climber. So they’re in demand. And there’s a summer tourist season built around the vineyards.

Climbing: Where did you pick up the construction skills you used to renovate the Airbnbs?

Bolger: You end up doing a lot of random stuff with the rope access. Over the years, I rendered facades and did other bits and bobs. So I picked up a fair few things there. But it was a lot of YouTube after that. If you put your mind to it and have the motivation, you can get it done. But I always liked fixing things. Bolting is like that too. It’s massively creative. Bolting for me has become just as important as climbing. It’s the way I maintain motivation. It’s the artistic creative element. It’s addictive. It’s hard to put into words.

Climbing: Speaking of bolting, my limited experience in places like Siurana and Rodellar is that you can look out at these valleys and see endless undeveloped rock—cliff lines everywhere. Is that an accurate perception? If you just kept hiking would you keep finding stuff?

Bolger: It comes down to access. A lot of the walls are either protected for wildlife or archeology, or they’re privately owned. So it’s pretty tricky, actually. I’ve found some amazing places and not been able to bolt. And I’ve found some amazing places, bolted with permission from the landowners, and then had them change their minds and make us de-equip the walls—which totally sucks. It’s a difficult business. But there is an amazing amount of rock. That’s what makes Catalonia stand out. It’s just ridiculous.

Climbing: Did you move there with bolting in mind? Is that something you’ve done for your whole career?

Bolger: No, I’ve definitely turned toward it. When I first came out to Spain, I was overwhelmed by the pure volume of rock, but I had to repeat some established routes before I could earn my right to start developing new lines.

Climbing: Tell me about E.L.L.I.E. Did you equip that?

Bolger. It was a cool process. I found the cave and bolted the first line, which is an 8c [5.14b], and several more. Even then I saw you could start way in the back of the cave, boulder halfway out, then clip into a rope and climb the rest of the way, but when I tried it, I was like, fuck, that’s desperate. Over the course of five or six seasons, I ended up piecing it all together, doing individual sections, and when I showed Alex Megos the cave, he did a few first ascents, including the first ascent of Pink Patatas, which is 9a+ [5.15a] and was the first route that starts all the way in the back of the cave. After he did it, I started trying it properly, and after I sent it, I started trying E.L.L.I.E., which is basically a harder variation. Instead of doing an 8c [5.14b] at the end, you do a hard 8c+ [5.14c], with some really precise and unforgiving moves on monos at the end. I fell there a couple of times. It felt like it would be torture forever. But then it happened. It was pretty mega, actually.

Climbing: What was the timeframe like?

Bolger: After I did Pink Patatas, I spent the spring 2023 season trying the harder variation, and I was getting pretty close, but I forced it a bit. I didn’t want to let it slip through my fingers, but as a result I worked myself into the ground, trying those moves too many times, insisting too much. I picked up some sore fingers, sore elbows. I had a sore left shoulder from the first boulder. It’s nothing out of the norm for hard climbing, but it all adds up. That summer, I went to Brazil and further tweaked a finger pulley, and when I went back to the cave that autumn, it just didn’t work. There were too many holds giving me grief. So I took a step back from the project and let everything heal up nicely. When I first went back this season, everything felt desperate, but I made massive progress every session, which was massively motivating.

Climbing: Did being forced to step back actually make the process easier, mentally?

Bolger: Well, it was a learning experience for me. It’s so easy to get caught up thinking that if you step back from it you’ll never get it done, but sometimes that’s exactly what you’ve got to do. It’s hard to know when to push and when not to. Realistically, I feel like I should know how to do this by now. I’ve been redpointing stuff for years. But climbing at your limit is an elusive beast. You never know when the day is going to come.

Climbing: I feel like it’s hard because, when you’re at your limit, it can feel unclear whether you’ll ever be able to build up the fitness to get back to your current fitness.

Bolger: Absolutely. And I’m 36 years old. Sometimes you begin to think that maybe this is the highest I can go. But climbing is one of these sports where the time frame is pretty incredible. I’m quite close friends with Iker Pou, and he’s 47 now, and he’s strong as hell. And he does not stop. He’s doing alpine adventures, then multi-pitching, then ice climbing, then back to Margalef, and he’s still climbing 9a. It’s not just impressive; it’s inspiring.

Climbing: I feel like people commonly associate aging with injuries—something that I’ve dealt with myself. But you’re famous for doing one-arm pull-ups on the Beastmaker monos. How can that feel so safe for you? Have you always been strong in that position?

Bolger: Not at all. The first time I came to Margalef, I was shit. I hated it. I remember there was a 6c [5.11] with a mono on it and I was like, “I can’t F-ing do this.” I even swore to my mate that I would never come back. But finding something I was weak at also made me really psyched to get better. And I did.

View this post on Instagram

That’s one really interesting thing about climbing: Our perception of what we’re good at can be totally skewed away from what we’re genetically disposed to being good at. We get good at the things we like, which tend to be the things we feel comfortable doing, which are the things we do the most. But what you’re actually physically or genetically geared toward could be completely different, except you haven’t been exposed to it, so you don’t do it that much, so you feel like you’re bad at it. It can be quite hard to find what you’re truly best at, but once you do, there’s something beautiful about pursuing it to your limit.

Climbing: You see that with Aidan Roberts, with his high-angle crimping.

Bolger: Absolutely. I really like that idea within climbing. Within running, it would be totally crazy for a sprinter like Usain Bolt to train for marathons. But in climbing, there’s this expectation that everyone does all the things and all the styles. That’s beautiful as well, because you can go try all these different styles. But I think there’s something pretty interesting about certain people dedicating themselves to a small aspect of climbing and seeing how far they can take it.

You might also like:

-

Kai Lightner Thinks We Can Do Better

-

The 15 Greatest Ascents of 2023

-

An Incomplete List of Alex Honnold’s Less Famous Badassery

The post Tom Bolger Shows How to Make Pro Climbing Work appeared first on Climbing.