Diving into Your Soul: Lessons from “Queer Eye”

The viewers at home can see it: Neal Reddy is not happy. He’s out walking his dog near his home in Atlanta when the five chatty, determined, opinionated stars of “Queer Eye” roll up in a pickup, and he’s clearly discombobulated.

He tries to run away. They run after him, laughing. When they catch up, the hugging starts.

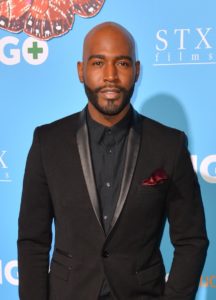

“You don’t like being touched?” asks Karamo Brown, embracing him anyway. Costar Jonathan Van Ness strokes Reddy’s long hair.

“This is so cool, that you guys are just touching me willy-nilly,” Reddy says, all sarcasm and nerves.

So it goes in “Saving Sasquatch,” the second episode of the Emmy-winning reality show’s first season. This, viewers know, is the “before” presentation of the “hero,” his quirks and issues brought to the fore.

Oh, look, he has a dog hair on his eyelash. He has a beard down to his chest. He has nice delts, as Van Ness observes with a cheerful little squeeze. He has a habit of wearing the same clothes for days and a tendency to keep people at arm’s length, using humor as a buffer.

He doesn’t like being vulnerable. He doesn’t like being open. He hasn’t had a visitor to his home in years, confirmed by the couch covered in hair, the bathroom covered in grime and the welcome mat that howls GO AWAY.

“And I can tell you don’t take a compliment well,” observes Tan France in those opening moments. “You look away every time we compliment you. But we’ll work on that.”

We’ll work on that: That’s the declaration, whether spoken or unspoken, that foretells the transformation to come. Reddy’s story begins with him in a state of pain and self-imposed isolation. In the next 45 minutes, he goes through his own version of a reboot, and by the end of the episode, he is resolved to get out socially, be vulnerable, be happy, and embrace life.

And so the “Fab Five” set to work. Van Ness cuts his hair and beard. Antoni Porowski helps him make some “nice little buttered leek Gruyère” grilled-cheese sandwiches. Bobby Berk aims “to get Neal out of this bachelor-pad cave that he’s living in, and get him a home that’s eclectic, it’s cool, it’s modern, it’s sleek.” France sets about upgrading his “hipster yogi” look, and they chat about their South Asian heritage — France as a Muslim Pakistani-Brit, Reddy as a Hindu Indian-American.

Most of Reddy’s friends, it turns out, have never even met his parents — so that episode-capping gathering at his home in a few days? That will be, for most of them, an introduction.

Just before the big event, Reddy says his goodbye to the stars, looking spry in the floral button-down and snug linen pants Tan picked out.

“This has been a completely weird and beautiful experience. I just want to thank you guys. I was in a big down spell, a really dark place. . . For some reason I didn’t want to fight my way out of it,” he says, getting a little emotional. “And that’s why this meant a lot to me.”

I Want to Believe

That simple narrative—the transformation from a dark place to a sunny place—is one we all want to believe in, and the way is filled with “happy tears.” The Fab Five cry. The heroes cry. The viewers cry, and I know because I’m among them. I’ve cried at probably eight out of every ten “Queer Eye” episodes that I’ve watched over the last couple of years, plopped on the sofa with my son beside me. He’d already seen the first two seasons when he floated it one evening: Mom, have you seen “Queer Eye”? Because I think you’d like it.

When I don’t cry, I’m disappointed, even a little resentful, as though somehow I’ve been short-changed, somehow the show has failed in its implicit promise to suck out my tears with a Shop-Vac and take me on a journey of challenges and catharsis and change. I always feel better, more hopeful, as I blow my nose at the end of an episode, even as I wonder about the tidiness of its arc. Because, come on, it’s reality television. I’m crying buckets, but I’m supposed to be crying buckets, right? How real could it be?

All persuasive storytelling is audience manipulation, after all—something I always kept in mind through decades as an arts journalist. In my years as a film critic, I often felt myself watching a movie on two planes, split personality at play, with the Average Viewer gasping and weeping at the designated plot twists while the Ornery Critic asked whether the film jerking my tears was genuine art or bullshit cliché.

This is all to say that I’m both built to cry and built to question why I’m crying. Sometimes we’re moved by skillful fakery. Sometimes we’re moved by authenticity. Sometimes we don’t know which. Reality-show fans are savvy enough to question the dramatic storylines and theatrical confrontations fueling episodes of, say, “Hell’s Kitchen” or “The Bachelor,” but “Queer Eye” is a show apart. Its central appeal is banked on the notion of authenticity. Epiphany and transformation are its hallmarks; emotional healing is its stock in trade.

“It’s a very positive show,” remarked Pam Rutledge, director of the Media Psychology Research Center at Fielding Graduate University in Santa Barbara. “People love it. . . . For the audience, everybody believes in Cinderella — so it’s aspirational.”

The questions remain: Are the show’s “heroes,” those weekly guest participants primed for change, genuinely better off at the end of an episode than they were at the beginning? Do those transformations hold? And does the show truly have something useful to say about emotional healing and mental health?

The Spontaneity Is Real

“It’s not therapy, right?” said Reddy in an interview with MIA three years after the episode was shot. “But it can be therapeutic.”

For him, it was transformative. Before the show, Reddy had never been in therapy. He had never opened up about his own depression. “It was my dirty little secret.” These days, “I’ve become way more open to talking to people about my mental health and depression and anxiety — and things that bog me down, and have bogged me down, in my life.”

That opening scene, where the Fab Five startled him? That reaction was real, Reddy said. Not fakery.

Reddy had assumed they would come to his house to greet him, and so, planning ahead, he came up with a speech to deliver. Then the producers told him he had an hour to kill — so, hey, why not take his dog for a walk? He did. As he did, they filmed him, supposedly to obtain “this random footage” of him doing “normal things.”

About 20 minutes later he heard a shout — Hey, Neal! — “and it’s literally the Fab Five in a car 50 feet from me,” he said. “And I full-on panic. . . . It was a legit flight response from me. I didn’t know what to do.” Missing from the episode is footage of Reddy running flat-out, screaming. In reality, “the neighbors were coming out. The producers were telling the neighbors, ‘Don’t worry. It’s fine.’”

In a way, Reddy’s kerfufflement was more real than the scene we watched from our sofas. In the episode we see Hero Neal backing off, being nervous and jokey as the “Queer Eye” team swoops in. What we don’t see is the extent of his alarm or, before that, the producers nudging him to head outside. His surprise was genuine, but it was all part of the game plan — a kind of engineered spontaneity that reigned throughout the week.

“They would only tell me the very bare-minimum information — like, ‘show up here at this time,’ ‘we’re gonna pick you up at this time.’ They didn’t want me to be an actor on the show.”

This is the standard template for “Queer Eye” production: Keep the heroes in the dark about a meeting or an event until the last possible moment. Spring it on them, cameras rolling. Capture their unrehearsed comments, their yelps and laughs and worried murmurs and fleeting facial expressions showing sadness or frustration or surprise or joy. Then gather them up, boil them down, pull out the highlights and piece them together in deftly edited form as an inspiring story of change.

Real Moments in Real Time

Consider the episode featuring Jody Castellucci, a hero from season three.

Her story, filmed in Amazonia, Missouri, shapes its superficial makeovers around one shattering whopper of an emotional revelation. But none of it was staged, she said on the phone. Cast and crew never instructed her on how any conversation should proceed. They just showed up and filmed everything as it unfolded “in real moments, in real time. There was nothing, not one thing, scripted. And it flowed.”

In her installment, “From Hunter to Huntee,” Castellucci is introduced as a hunter and prison guard who has stopped taking care of herself. As with so many “Queer Eye” plotlines, little things flag the need for transformation: The fact that she hasn’t had her nails done in forever. The fact that she hasn’t had a haircut in forever, either. The fact that she mostly wears camo.

“I think Jody’s fallen into that I-don’t-care state,” says her husband, Chris, at episode’s start. “She’s always beautiful to me, but I don’t think she feels that great about herself.”

The Fab Five set off to help make her feel beautiful again — hair, clothes, the usual. But then, Castellucci said, “Karamo dived deep.” He asked her when, exactly, she quit taking care of herself.

“It made me look way back,” she said. And she was surprised by what she found. “I was like, ‘Oh my God, this started 26 years ago when my brother died. And before that, I did take care of myself.’ . . . But after he died, I quit cutting my hair, and I really just put myself so far on the back burner, I just didn’t care.”

Look how it affected her, she said — “and I didn’t even know. So it definitely goes along with mental health. With me, anyway.” She didn’t have issues with it going into the show, “but we all do. . . . When you don’t take care of yourself, you’re going to be mentally depressed. You’re going to be suicidal in some cases.” Some might turn to drugs. “But it’s all mental. It’s all a mental-health thing to me, really.”

The need to peel back defenses and talk about life struggles — or even think about them — is underscored again and again on “Queer Eye,” usually with plain talk about emotions. Most episodes don’t employ any psychiatric terminology whatsoever. They aren’t about pathology; they’re about people. And people feel pain.

“When you’re down and out and depressed, you know, it covers all ages. . . It can hit you at any time,” said Kenny Yarnevich, the focus of a season-four episode out of Kansas City. When it hits, “It’s so important to try to find ways to help yourself out. … and these shows that they do, so many people tell me that they’re so uplifting. That’s why they’re so popular.”

The Healing Power of a Makeover

The series is a reimagining of the 2003-2007 Bravo series, originally titled “Queer Eye for the Straight Guy,” which featured a team of five gay men putting some zing back into the clothes, home, food, grooming, and culture of (mostly) hetero fellows in need of restyling. Since its debut in early 2018, the reboot has streamed 47 episodes over five regular seasons, one mini-season in Japan and a special in Australia. (Production on the new season was halted by COVID-19 and has been delayed until an undetermined date. The company declined to arrange “Queer Eye” interviews before then, and producers and stars did not respond to independent press queries.)

The new show, with its new Fab Five, keeps all the elements intact, but with a fresh, therapeutic twist: Episodes now use those zingy transformations as springboards for the heroes’ healing and personal change. Installment after installment, swooping in on participant after participant, it sends the repeated messages: Take care of yourself. Be kind to yourself. You’re beautiful. You’re good. We love you. Love yourself. Or, in the words of Van Ness: Yass, queen!

Each hero’s story unfolds over the course of a workweek, with the stars all taking their turns: France guiding on fashion, Porowski on cooking, Berk on home or other renovations, Van Ness on hair and beauty. Brown, the “culture” authority and a licensed social worker trained in psychotherapy, is the point-man for emotional troubleshooting, digging down into each participant’s unspoken hurt and unresolved conflicts.

Heroes are nominated by a friend, a loved one, maybe a colleague. The nominees are vetted; the non-disclosure agreements are signed; the friends and loved ones and colleagues are interviewed for insights into each hero’s character and travails. And then the swooping-in begins.

On the first day, the Fab Five drive up to a hero’s place and say hello. They wander through it, analyzing its quirks and clutter, with Jonathan sniffing at expired food in the fridge and Tan yanking plaid shirts from the closet. In the days that follow, they fix their heroes’ hair crimes at the salon, take them shopping for new clothes, teach them to make homemade guacamole or a nice crab boil, outfit their home with smashing new features — and get them talking about their seclusion or self-doubt or failures at self-care, their estranged or troubled relationships, their need to face their demons and seize the day.

Then they say their goodbyes, always with hugs, often with happy tears, leaving their hero to sashay off to some party or public event, where they invariably wow friends and family with a hot new outfit and a sparkling display of freshly won confidence. And the Fab Five, hunkered down in their temporary digs, cheer them on as they watch it unfold on TV.

Some episodes have striking subplots of reconciliation. In one, Brown sets up a meeting between a hero in a wheelchair and the guy who shot him; in another, there’s a reunion between a man and his estranged adoptive mom. Occasionally, the “Queer Eye” team helps out a small-business owner who’s coping with one hurdle or another: The mobile pet-groomer whose RV broke down, or the Philadelphia gym owner whose cramped work and life spaces barely leave room to breathe. Other episodes tell quieter tales of grief and inner yearning.

Not a Failure

Yarnevich, for instance. His episode, “On Golden Kenny,” has become a fan favorite both for the aching sweetness of its hero and the gentle concern expressed by the stars. At the start, the 64-year-old retired bachelor is living alone and grieving the death of his dog, Bo. Fur, dust, and clutter are everywhere in his home, which he inherited from his parents and has kept intact since their deaths. It looks like a time capsule from the late 1970s. In his baggy sports shirts and mustache, so does he.

He’s committed to his Catholic church community, running its club, bar, and bowling alley as a volunteer. But he doesn’t really socialize beyond that. He doesn’t do much for himself. He always puts himself last. He hasn’t had anyone in his home, including his large and close-knit Croatian-American family, in 15 years. He can’t remember the last time he had a good time, he confesses to Karamo. He loves his brothers and sisters, he says, and they love him, but they all took off with their lives. He didn’t. He’s been stuck. “I just always compared myself and think back, ‘Well, I’m a failure.’”

But he isn’t, Brown tells him. Yarnevich is loving, and he took care of his parents for years.

“You are not a failure,” he declares with quiet urgency. “You’re not a failure.”

Yarnevich cries. Karamo reaches out, grabs his shoulder. They share a long look.

“You hit it right on the head,” the hero says, crying. And we cry, too.

In the course of the episode, Bobby takes him shopping for new furniture and home accessories, bringing his house into the 21st century for a family gathering at the end of the week. Tan outfits him in hip glasses and button-down shirts. Antoni teaches him how to make a Croatian squid ink risotto. Van Ness snips back his longish hair and shaves off his “G2G” (“got-to-go”) mustache.

Even better, cueing even more happy tears: They take Yarnevich to an animal rescue and help him find a new dog, a chow-shepherd mix that reminds him of Bo. He weeps, overwhelmed, and names him “Fab Five.” He weeps again when he tells the guys goodbye.

“Without a doubt,” Yarnevich recalled on the phone, “they got me crying.”

During shooting, the element of surprise never bothered him, he said. He simply surrendered to it. “They put me up in a hotel for four and a half days, and picked me up every morning. I never asked what we were doing or where we were going… I knew I was in good hands.”

And no, it wasn’t staged. “Queer Eye,” he said, “Tells about a person from head to toe. There’s nothing phony, there’s no cue cards, no ‘You have to do this.’ There’s none of that. It was all genuine, original. They were, also.” He often tells people: “If you really want to know me, watch my show.”

Yarnevich, at least, knew what he was getting into. By contrast, the early participants in the reboot “really had no idea what the show was going to be about . . . . We were just flying blind from the get-go,” Reddy said. “I had no idea this show was going to be about an actual transformation.”

He was only familiar with the original show — and only expecting a few smart redos of his home and wardrobe. “I almost felt like I was scamming them,” he said. Instead, he found himself exposed to “a total-life kind of thing, that’s kind of fueled by these exterior things — such as your house, such as your appearance, such as your clothing. But ultimately, the whole goal of the show for us, as heroes, is they wanted us — they cared enough — they wanted us to sort of jumpstart a change in our lives.”

Every twitch in that jumpstart was filmed. As his own week progressed, Reddy said, they amassed hours upon hours of footage. Kevin Abernathy, a “Queer Eye” hero from the fifth season, said each little snatch of dialogue heard on-screen was culled from something “at least an hour and a half to two hours long. . . . So they were long. They were long. A lot of things were talked about.”

In her own recollection, Castellucci said she was usually so focused on any given moment, with any given star, that the throng of people around her barely registered. “Watching it afterward, it was. . . ‘Oh my gosh, I remember that conversation, but I don’t remember all those people being there.’” It all felt so “comfortable,” she said. “You’re just sitting around having a conversation and talking about your life, and being asked questions—like, Karamo, you know. You can just spill your guts.”

A Different Take on a “Different” Week

All of that filming, all of those conversations, all of that guts-spilling: Fourth-season hero Brandonn Mixon experienced it, too. “The week, it was very different,” he said.

Mixon, featured in the Kansas City episode “Soldier Returns Home,” described his time on “Queer Eye” as intense and often disorienting. As with all participants, he was uninformed of planned trips and interactions until shortly before the shooting began — and conversations went deep fast. “It was some really powerful stuff, and, like, ‘Man, this came out of nowhere.’” And to him, yes, it felt staged. “Not in a bad way, right? But it was hard on me.” The aim was to “get deep really quick. And so that was really weird.”

In the Mixon arc, he’s portrayed as a veteran of the war with Afghanistan who never quite resettled into civilian life after his medical discharge for a traumatic brain injury. A husband and dad, he spends the bulk of his time away from home, building tiny houses for veterans through a nonprofit he helped start, the Veterans Community Project. In the episode, he opens up about grappling with depression and worries about drifting from his wife.

“I’m nervous,” he tells Brown. “I’m scared. Opening myself up makes me feel vulnerable, and I don’t want to be vulnerable.”

In a phone interview, Mixon said the show’s portrayal didn’t fully capture him. In fact, he said, “I thought my whole story was going to be about this military tension between Tan and I” — the one a Muslim, the other an American veteran deployed to a Muslim country. Right away, they cleared the air. “We had that type of relationship where we really kind of understood each other, and really respected each other because we really got that off our chest in the beginning,” he said. He was disappointed when that aspect of the story failed to make the final cut.

Also on the cutting-room floor: Much of his conversation with Brown, which flew through numerous topics and wound up reduced to a clip. “It’s like, ‘Bam! Here you go! Filming!’” Then, after they rolled away, “It’s like, ‘What the fuck? We really got serious there for a minute.’”

As a result, “I was having a hard-ass time trying to process everything. . . . . I was going through some hard shit, because they brought up some hard stuff — but again, they’d just walk away.”

Mixon emphasized repeatedly that he did not aim to go negative on “Queer Eye.” He’s not “hating on” it; that’s just how filming was. “My story, it’s a good story,” he said. But he thinks it could have been, maybe should have been, pieced together to tell a different one, both in the wider narrative and in the dialogue with Brown. The most meaningful conversations occurred behind the scenes, with the crew. But on screen, in the version portrayed for the bingeing viewers, “Karamo was kind of the savior.”

Getting Down “Into Your Soul”

Karamo (kah-RAH-mo): The starter of conversations and unearther of buried truths. Castellucci and others spoke of him in almost mystical terms.

“I always say, he gets right into your soul,” she said, “and pulls stuff out that you’re trying to keep away from people.” She felt like she ought to pay him some high-priced fee. “I think he’s a life coach, he’s a therapist, he’s everything like that — but he’s Karamo, and nobody is like him.”

“He can really get down into your soul,” agreed Kevin Abernathy. “He can bring out everything — clean you out, so to speak, with a good, crying cleanse.”

In Abernathy’s episode, “Father of the Bride,” he meets the Fab Five at a critical juncture: His daughter, Haley Ferrigno, who nominated him, is about to get married and move out of his home in the Philadelphia area. In the years since her parents’ divorce, he’s stopped taking care of himself. He puts everyone’s needs ahead of his own, including his ex-wife’s: The Fab Five are aghast to find her clothes in his bedroom closet, his clothes in the basement.

He lacks confidence. He puts himself down. He’s hesitant to go out, hesitant to start dating, hesitant even to smile with some missing teeth. And he uses way, way too much product in his hair – “this kooky-baby Eric Trump gel,” says Van Ness, who also cautions Abernathy on his lack of self-regard. “Gotta have that self-love, queen,” he tells him. “Yes, yes, yes.”

That, Abernathy said, was a major takeaway. “Yeah,” he said. “Because back then I didn’t really love myself. . . . Now, I’m not saying that the makeover was the end-all, the be-all, but it helped me get the feeling of loving myself back again.”

Van Ness spiffed him up with a crisp new hairdo, and France spiffed him up with a crisp new wardrobe, including jackets that fit following a weight loss. The show arranged for partial dentures to fill the gaps in his grin.

“Oh, my God,” Abernathy says, gazing in the mirror and touching his face with joy and wonder. “My smile is back.”

He hugs the dentist. Hugs Van Ness. Happy tears commence.

In the middle of the episode, Brown drops one of his bombs: “Do you know why you’re afraid to be alone?”

It dates back to his divorce, Abernathy says. He tried to move on but couldn’t — and now his daughter, his “rock,” is poised to leave.

“I want you to understand something: You’re not alone,” Brown tells him. Relationships evolve, “but you have to grow with them. You have to be open to all these new, amazing chapters in your life.”

As Karamo moments go, this one is fairly typical, both in its timing and its insights. “He’s really good at staring into your soul and having conversations with you,” said Ferrigno. The result is “a little bit like therapy — someone that’s listening to you, unbiased.”

The Therapist

In fact, Brown isn’t simply behaving like a trained therapist. He is one, something the show does not make clear. Rutledge — the media psychologist — wishes it did. She wishes it identified him as something other than its “culture” expert, a holdover from Jai Rodriguez’ role as “Culture Vulture” in the original series.

In his 2019 memoir, Karamo: My Story of Embracing Purpose, Healing, and Hope, Brown describes the skills he acquired in his former line of work and his resolve to redefine “culture.” “I’ve learned how to become a blank slate, maintaining a posture of reticence and neutrality. . . I’ve learned how to ask questions in a way that makes whomever I’m speaking with see me as the person they need me to be in that moment, in order to reveal the source of their distress.” In auditioning for “Queer Eye,” he writes, “I was going to try to be the show’s psychotherapist/life coach/emotional mentor: whatever you want to call the person who fixes the inside.”

Brown also addresses his own struggles with addiction and depression, including frank talk of a 2006 suicide attempt and a direct appeal to anyone in danger to call the National Suicide Prevention Hotline. “I felt like my life was over,” he says. “There was no point in existing. But I was given a second chance . . . . Each day is a new day for me to continue to focus on my mental health. The same way that people get up and go to the gym to make sure their body gets exercised, or try to eat healthier, I continuously make decisions to make sure that my mind is strong.”

His castmates have, in different ways and at different times, opened up about their own mental health. “When I was growing up I had a lot of anxiety attacks,” Porowski told Yahoo News, adding that he initially saw his anxiety as a weakness before seeking help with a social worker, therapists, and mentors. As a result, “I realized that it’s a part of me and it’s not going away,” he said. “So I might as well learn how to work with it and cope with it.”

In his own memoir, Over the Top: A Raw Journey to Self-Love, the non-binary (“he/she/they”) Van Ness talks about his experiences with trauma, sexual abuse, addiction, living with HIV, and growing up gay in the Midwest. In Naturally Tan, France talks about growing up gay and Muslim. And on various episodes of the show itself, Berk talks about growing up gay in a conservative Christian church, which remains a deep and obvious source of his own pain.

In this way, the Fab Five’s queerness, so clearly front and center, allows them to connect with the show’s participants with an openness and vulnerability that come across as authentic—even for those who might never before have spoken with an LGBTQ person. And vulnerability is, as always, the mantra.

Baby Steps, and the Mental Health Spectrum

At one point in “Saving Sasquatch,” Jonathan Van Ness calms Reddy’s nerves as he pares back his beard and hair.

“Neal is a little baby guinea pig with anxiety, honey,” he observes to the camera. After a newly shorn Reddy hugs him with gratitude, he adds: “You can’t selectively numb feelings. So if you try to numb the vulnerability, you also numb joy, happiness, connection.”

On “Queer Eye,” haircut epiphanies are not unusual. Such moments and insights, said Reddy and others, point to the show’s portrayal of mental health as something everyday and universal, breaking down its climactic metamorphoses into doable, relatable “baby steps.” There’s no them and us, no either/or, in this model. Everyone’s affected in the quest for mental health. And everyone’s affected differently.

“It’s not a binary thing,” Reddy said. “It’s so complex, and so individualized. And there are some generalized things that kind of cross between people — and experiences that are shared. But for the most part, I think, we all have to kind of learn to accept that it’s not going to be the same for everyone. People need to figure out what works for them.”

Rutledge sees mental health as a “continuum” from joy to despair. Some folks might have a higher baseline optimism than others; some might have higher baseline anxiety. “It’s all sort of part of a larger picture. And therapy is a way to say, ‘Where am I now? And where do I want to be?’”

We who watch and weep are engaging with the heroes, connecting with them, maybe learning from them — assuming we find the parallels with our own lives. “This is an opportunity to bring people along and transform them. . . . It isn’t just getting your nails done,” she said. “Not that there’s anything wrong with that.”

What “Queer Eye” does right, she said: using exactly those everyday, relatable words to describe emotions and issues rather than terminology loaded with stigma and knee-jerk stereotypes. Everyone, by definition, should want to improve their mental health — “but even that term is pejorative” in a lot of people’s eyes, Rutledge said.

She questions the costly nature of the series’ transformations, which are way out of reach to the average viewer. And if the show were more overt in promoting therapy as something helpful and accessible, she said, it might persuade viewers who are uncomfortable with the idea. Too many people don’t view mental health on a spectrum. Too many are influenced by the stigma—“and psychology is a lot to blame for this,” she said, noting the longtime emphasis on pathologies and the more promising emergence, in the 1980s, of a positive-psychology model that promotes the idea of therapy as a tool for growth and happiness.

This is what “Queer Eye” should be saying out loud, she said. “I think that’s a missed opportunity. . . . I don’t think that they necessarily should drag the heroes through in-depth therapy. I just think there are ways where this can be framed where they acknowledge that it’s therapy, that therapy has value for all kinds of things.” Again, what would help: “Letting Karamo own it a little bit more.”

Kevin Barhydt, author of Dear Stephen Michael’s Mother — a forthcoming memoir of adoption, abuse, addiction and recovery — doesn’t see any of that as a shortcoming. People already know about therapy, he said. The show combats assumptions simply by telling stories.

For example: the mini-season in Japan. Barhydt found solace in it with his wife, who’s Japanese, after losing her mother to cancer. He noted the season’s opening hero, Yoko, a selfless Tokyo hospice worker who gives all the space in her home to those in her care. She sleeps on the floor under a table. She grieves the death of her sister and sees no cause to take care of herself at all. In a moment of heartache notable even for “Queer Eye,” she tells Brown that her own life ended when her sister died.

The show cracks open the conversation regarding Yoko’s pain and, Barhydt said, tackles the entrenched cultural reluctance to discuss such issues freely in Japan. “What they’re saying is, ‘We understand this is a stigma, and we’re going to talk about it in a way that will reduce the stigma. We’ll bring it down to a place where we’ll discuss it not casually, but comfortably.’”

The message is clear, he said: The power of resilience and the healing nature of community. Quoting a maxim from Narcotics Anonymous, he added, “The therapeutic value of one addict helping another is without parallel.” Swap in “person” for “addict,” and you’ve got the essence and impact of the show. “‘Queer Eye,’” he said, “has always been about breaking down these walls.”

The Therapeutic Lessons of a Story

Brandonn Mixon gets the message. He gets the impact on viewers, though the chief positive effect, for him, was the boost it provided for his nonprofit, VCP. That’s why he did the show. “Yeah, I did talk about my mental issues a little bit,” he said, “but again. . . it could have been covered in different ways. I don’t think it did a very good job of showing what, exactly, I went through or how I was feeling.”

In the end, Mixon felt the show portrayed him as someone in a story — a feeling reflected in his Instagram bio, which describes him as a “#queereye Season 4 character.”

Not hero, not participant. Character.

But to viewers at home, the narrative is all: It’s how the show frames its lessons on healing. The arc of each “hero,” with the emphasis on overcoming some form of adversity — social isolation, a cluttered home or business, failures of self-care and self-love — whisks its viewers away as the best-told stories always do. The “Queer Eye” “happy tears” are triggered by empathy, connecting viewers with trials, tribulations and triumphs that affirm their own feelings and nurse their own hopes. It helps us to watch others being helped.

Across social media, whole discussions are devoted to the shedding of tears. A few weeks ago, on the “Queer Eye” Facebook fan page, Caitlín Hardman posted a question that prompted many comments and numerous heart emojis: “My husband just said ‘how do you watch an episode of queer eye without crying, and if you do are you even human?’”

More recently, responding to interview questions via Facebook Messenger, Hardman described the effects on her own mental health.

“There are things I pay closer attention to now because of things I witness and see on the show,” she said. “Things like my mental health, my feelings, my identity, my clothes, my values, etc. These are things that I easily avoid due to my anxiety. The Fab 5 brings them to my attention in a comforting and non-triggering manner.”

Another fan page member, Nozzie Johnson, said she appreciates the vulnerability on display, in both the show’s participants and its stars. “As a Highly Sensitive Person (HSP) and a person who operates pretty much on feelings and connections,” she wrote, also via Facebook Messenger, “QE is like a drug for me! It has all of the elements that fill me and satisfy me. Openness, real stories, connection, change, inspiration, hope, equality.”

Castellucci, a “Queer Eye” fan as well as a hero, sees healing as the roots of its feel-good popularity. “It touches somebody who’s going through the same things and feels the same way. And it’s not anything negative, so it’s a breath of fresh air to see something positive,” she said. The show “makes you feel good and alive and healthier, mentally, because you see what’s going on with yourself.”

While Abernathy doesn’t really see the show’s lessons and plot arcs as matters of mental health, his daughter Haley does. “It’s not like blatantly, in-your-face, ‘Today you’re going to talk about mental health.’” But it’s definitely there, she said. She noted her own lived experience in that regard, coping with depression and anxiety and getting treatment for same.

The show’s advice on self-love, self-care—all of that adds up, for viewers and heroes alike. Ferrigno described that little moment in the show when France called out her father’s self-deprecatory humor. “I remember watching that and saying, ‘See, Dad? Don’t always make fun of yourself. There’s a root of that that’s not happy with yourself, that can really fog up your brain.’”

At week’s end, when she first caught sight of her transformed dad, his posture was straight. He looked confident. His presence was stronger. He seemed at ease in the world. And that, she said, was “amazing.”

Echoes of the Fab Five

The show “brought out a part of me that I had deep down inside,” Abernathy said. Since his episode first streamed in June, he’s faced one massive setback: losing a leg to diabetes. Ferrigno’s GoFundMe page has raised more than $15,000 toward modifying his home, though some of Bobby’s earlier touches — including a touchless faucet — already help.

“It’s just been another chapter that I have to go through, and as best I can,” he said, exhibiting the same quiet calm he conveys in the show. “And you know, I have help. I have Haley helping me, and everything.” Soon he’ll be starting rehab with his new prosthetic leg.

And soon after that, he hopes, he’ll be able to go on dates — though the logistics are complicated. “One part of my brain’s telling me, ‘go,’” he said. “The other part of my brain’s telling me, ‘Not yet.’”

Other insistent voices are having their say, as well: Like other heroes, and plenty of fans, he hears echoes of the Fab Five banging around in his head: Jonathan saying “self-love, queen!,” Tan telling him to put on his jacket and go out, Bobby telling him to show off his house to his friends, Karamo telling him to let go of his negative thoughts. “You’ve just gotta go for it, Kevin.”

When Yarnevich goes to cook, he hears Antoni. When Castellucci looks in her mirror, she sees Jonathan. Over the last year and a half, they keep popping up — part of the show’s enduring effect on her life and her psyche as she reminds herself, each day, that she’s beautiful.

For Reddy, the lessons of “Queer Eye” linger as he presses forward—with acting, with comedy, with his marketing and design work and his continued path toward healing. “I’m glad I have a therapist now . . . . I’m glad I’m able to talk to people about mental health, and I’m honored that me showing some of my mental-health struggle on Instagram has helped other people.”

Yarnevich hasn’t gone the therapy route, but he hasn’t ruled it out. Just as he heads off to the doctor or a dentist when the need arises, “If I think I need some therapy. . . I will seek help.” Yes, he still has his ups and downs — “being single, you still get depressed once in a while” — and yes, the pandemic makes it harder on everybody. (Having a dog helps: “I love him to death,” he said, adding that he shortened the name to “Fab,” because “‘Fab Five’ was a tongue twister.”)

But the show “rejuvenated” him, he said. Asked to describe its impact, he did not hold back: “That week was the best week of my life.”

Reddy looks back on his own five days with “Queer Eye” and sees that it broke him out of a cycle. “And because I had that one week of separation, and one week of people caring about me, and one week of people talking to me, the ripples are there now. That one week has allowed me to have all these other weeks since then.”

These days, he’s less blocked in expressing his feelings, he said. He now looks at his emotional goodbye speech, the one he delivered in his sleek new home with his sleek new coif, and regrets that it isn’t even more emotional. If only he had allowed himself to all-out cry, he said. But from the viewers’ vantage at home — slouched in our PJ’s, tissues at the ready, poised for epiphany — it’s still pretty darned cathartic.

“All of those, like, weird laughs you heard? That was the first time in a long time I’ve just been, like, joyful,” he tells the Fab Five. “Genuine joy, right? That was bred from my pain. When I started out the week, I felt like this was just highlighting, like, what was wrong in my life. And by the end of the week, I realized it wasn’t highlighting what was wrong in my life, it was showing me, like, how good my life could be if I just cared.

“I don’t have to change overnight,” he continues. “It’s not going to be perfect. But it did give me a glimmer of hope. There could be a different option for you — and that’s the most powerful part of this whole week.”

He thanks them again, and the Fab Five stand and hug him. This time he doesn’t run away. He doesn’t shrink. Instead he hugs back each of them, hard, closing with cheers and a group embrace that’s actually his idea.

There’s only one thing for the viewer to do.

Cue happy tears.