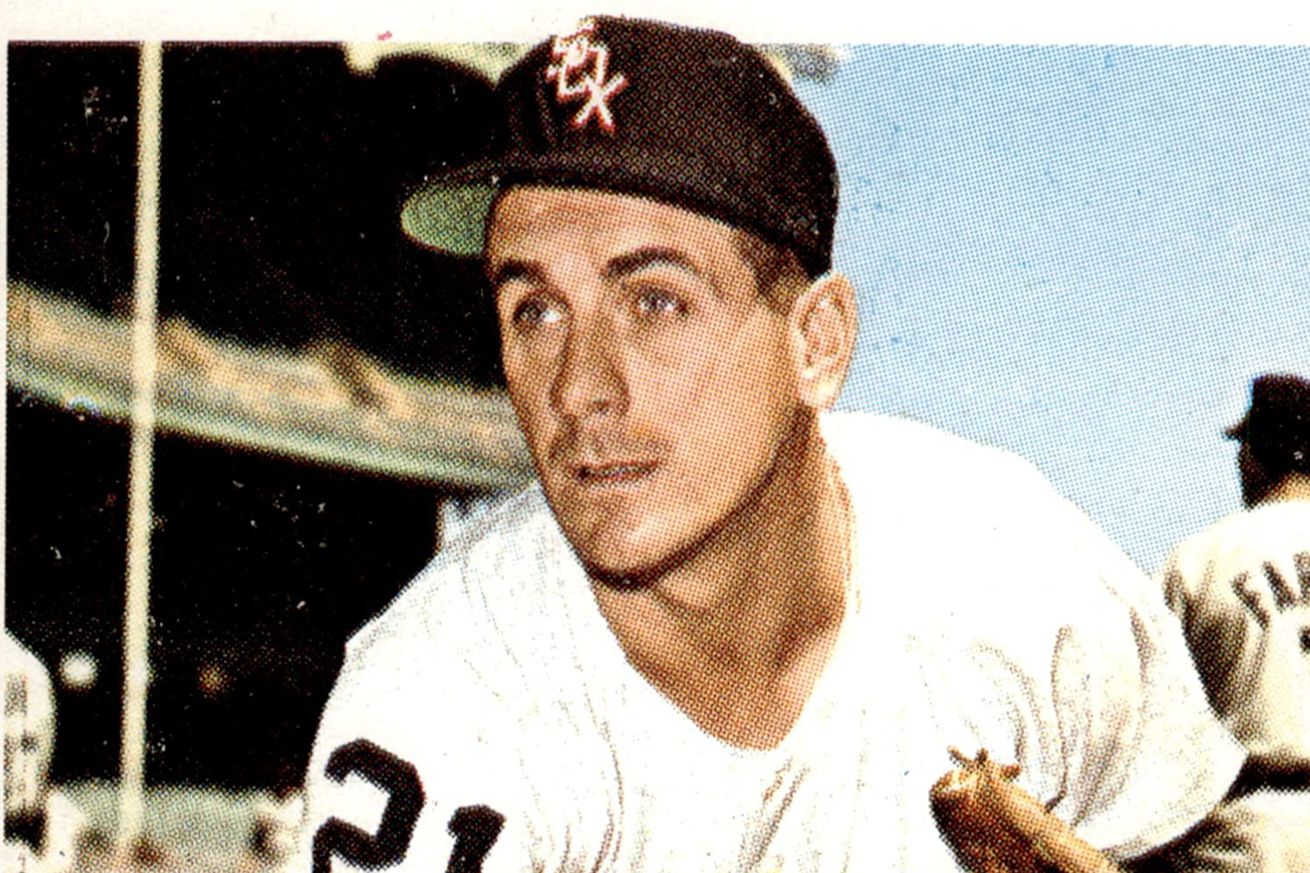

Ray Herbert, 1929-2022

A 20-game winner and All-Star on the South Side, our tribute comes in the form of a detailed Q&A from the archives

No sooner had we heard of the passing of Gary Peters on Thursday than we learned that his former teammate and rotation mate, Ray Herbert, had died back on December 20, of Alzheimer’s.

As in the case of Peters, Mark Liptak has an extended interview (originally published at White Sox Interactive in 2004, edited for publication today) with the former 20-game winner and White Sox All-Star, which we present here in honor and tribute to Herbert.

The early 1960s were a time of change for the White Sox, and in this case, change wasn’t good.

The “Go-Go” Sox of the 1950s, a team built around pitching, speed and defense, was changing. Players like Early Wynn and Billy Pierce were slowing down. Dick Donovan had been traded. Nellie Fox and Sherm Lollar weren’t the players they once were. In addition, team owner Bill Veeck insisted that the Sox couldn’t keep winning without more power, sacrificing young, future All-Stars like Norm Cash, Johnny Callison, Earl Battey, Don Mincher and Johnny Romano (all of who became home run hitters) for older sluggers like Minnie Miñoso, Gene Freese and Roy Sievers (in fairness to Veeck, he had wanted to acquire Orlando Cepeda and Bill White, but was turned down).

The White Sox bashed a team record 138 home runs in 1961 (including seven grand slams) but were in last place as late as May 24. They put together a 12-game winning streak in mid-June that brought them back into the first division, but wound up in fourth place for the season, at 86-76-1.

Something wasn’t right with the Sox, and something had to happen to change the philosophy back to what worked for a decade: pitching, speed, pitching, defense ... and still more pitching.

That something took place in June 1961, when the White Sox pulled off an innocent deal with the Kansas City Athletics that would reverse the team’s fortunes and philosophy.

The deal itself was unusual, in that by the time it had been completed the two men responsible for starting it were both gone. On the White Sox side, Bill Veeck had sold ownership of the Sox to Art Allyn; with the A’s, Frank “Trader” Lane, the former great Sox GM, had been fired by A’s owner Charlie Finley (who took on the GM duties himself).

The deal was completed on June 10, 1961 and saw the Sox get veteran pitchers Ray Herbert and Don Larsen, third baseman Andy Carey and utility outfielder Al Pilarcik for pitchers Bob Shaw, Gerry Staley, outfielder Wes Covington and minor league outfielder Stan Johnson. (White Sox author/historian Bob Vanderberg provided the details of the trade, along with this tidbit: “Frank Lane later told me that Charlie Finley thought he was getting Sox outfielder Floyd Robinson in the deal. Finley got Robinson and Johnson mixed up! It was Floyd’s first year and he wound up hitting around .310.”)

Herbert won nine games in the second half of the 1961 season, but more importantly he showed the new ownership group that you can never have enough good pitching. Juan Pizarro was already on the team, having been acquired before the season started, and Gary Peters and Joe Horlen were both very close to becoming White Sox stars. The pieces were almost in place. Johnny Buzhardt and Eddie Fisher were acquired before the start of the 1962 season. Hoyt Wilhelm came in January 1963. Tommy John would come in 1965.

The White Sox suddenly had pitching to burn: Good pitching, dominant pitching, and suddenly the Sox began winning 90-plus games a year. Perhaps you could go home again. The Sox came back home to the pitching-first ideal.

Somebody had to be first, though. That somebody was Ray Herbert. Herbert won 20 games in 1962 and was the winning pitcher for the American League in the second 1962 All-Star Game, played at Wrigley Field. In 1963, Herbert put together a streak almost unmatched in baseball history: four consecutive, complete game shutouts, a scoreless streak of 38 innings, and seven shutouts on the season to lead the American League. He still was an effective pitcher in 1964, but missed time with an elbow injury — an injury that eventually led him to being traded to the Phillies before the 1965 season.

Herbert, who had been in the major leagues since 1950, showed that pitching was the key to team success.

In this interview, with Herbert retired at 75, speaking with me from his home in Michigan, he talked about subjects ranging from how it feels to pitch in an All-Star Game, to how a pitcher can throw 38 straight scoreless innings, to what Al Lopez was like to play for, to his famous “called shot” home run in Boston in September 1962 (and how his teammates reacted to it,) and memories of the guys who caught him during his time on the Sox (Sherm Lollar, J.C. Martin and Cam Carreon).

Mark Liptak Ray, the White Sox acquired you in June 1961. Do you remember how you found out about the deal — and what was your reaction to it?

Ray Herbert We were in Detroit, and I got called into our manager’s office. Joe Gordon told me I had been traded to the White Sox. Any time a player gets traded from a last-place team to a contender, he’s always happy, and the Sox were always a contender for the pennant.

You wound up winning nine games in a half-season’s worth of work. Pitching coach Ray Berres may have been the best pitching guru in the major leagues at that time. Did he suggest any changes to you?

The first thing that Ray would do is take you out to the bullpen and watch you throw. He immediately suggested some minor corrections, and also suggested that I use my slider more. I didn’t really throw a curve that well, and the slider gave me something different to throw to the hitters.

What kind of pitcher were you? What did you throw, for example?

When I was coming up, very few teams had pitching coaches in the minor leagues. Usually it was just some ex-pitchers that helped out in the organization. You pretty much had to learn for yourself by trial and error ... take something out to the mound, and see if it works. It wasn’t like today!

What I learned, sometimes the hard way, was to throw strikes and keep the ball down. I threw three-quarters and had a natural sinker. My pitches would break down-and-in to hitters, especially right-handers. My fastball was in the 90’s, and I tried throwing a curve, although it was never really that good.

You had pitched in the majors for nine seasons before 1962, so you were very experienced. But it all came together that year, as you went 20-9. What was that year like for you? I imagine your confidence was sky-high any time you took the mound.

Working every fifth day gets you into a groove. You refine your control, and that gives you confidence. It gets to the point where you always seem to get ahead of hitters. You throw one strike, then two strikes, and the hitters become defensive with their swings. Pitching in Chicago also helped. That was a big ballpark, a pitcher’s park, and we had a great defense. I was a ground-ball pitcher, and the guys behind me — especially in the middle of the infield — would make the plays.

Any hitter in particular give you a lot of trouble?

Tony Kubek of the Yankees. Tony was a lefthander, and he never tried to pull the ball. See, my philosophy was to pitch strong hitters away, but all Tony did was go the other way. He’d punch a ball or two, either out to left field or right up the middle. He’d never try to pull — even in Yankee Stadium, where the fence in right was only 295 feet.

In late July of that year, you were named to the All-Star Team, as a replacement for the injured Ken McBride. How did you find that out, and what went through your mind?

We had been in New York. It was a Sunday, and we were on the plane flying back to Chicago. Al Lopez walks up to me and said something about a guy getting hurt, and that they wanted me to replace him. Actually, I thought that the reason they picked me was because the game was in Chicago and we were flying back to Chicago, so all they had to do was give me some cab money to get to the game [Laughing].

It happened so quick that you didn’t have time to think, “Wow, I’m going to the All-Star Game!” Unfortunately, my wife and family weren’t able to get down to see me play. They were in Michigan, which is where my home in the offseason was. It just happened so fast, they weren’t able to make arrangements to come down.

Did you know you were going to pitch in the game?

Yes, but I didn’t have a lot of time. Ralph Houk was the manager that year, so I get to Wrigley Field and I go into the locker room. Houk comes up to me and says, “We’re down to four pitchers today, you’re pitching, and you’ll go second.” Which meant that I’d throw the middle innings. In those days, they played two All-Star Games, and a lot of guys on the club had all recently pitched so they weren’t available.

[The first game in 1962 was in D.C. Stadium on July 10. The National League won, 3-1. This game was played on July 30, at Wrigley Field.]

Mark Liptak In that game at Wrigley Field you pitched three innings, allowing no runs on three hits (one of them an infield single from Willie Mays), and got the win. Tell me how you felt pitching that day, facing guys like Mays, Stan Musial and Frank Robinson. Were you nervous?

Ray Herbert Mark, I played my whole career and never thought about who I was facing in a particular at-bat. I always had the ability to focus and concentrate on the now; I never worried about the future, and I still don’t. I never considered “Oh, I’m facing Willie Mays,” or, “That’s Mickey Mantle.” To me, it was just like going to work. That was my job, playing baseball. I was never nervous; I did what I had to do. Now, I respected those guys, they were great players.”

[Herbert pitched the third, fourth and fifth innings, facing 10 hitters. He allowed an infield single to Mays, a single to left by Kenny Boyer and an infield single from Dick Groat. He induced a pair of double plays, and finished his work getting Hank Aaron to ground out. He was the winning pitcher in the AL’s 9-4 win.]

Mark Liptak Did you ever hear the crowd, or think, “There are 40,000 people watching me?”

Ray Herbert You hear the crowd, of course. You know that they are there, but with me it never entered my mind. I did what I had to do.

In 1962 you went 7-4 in the first half, then exploded for 13 wins in the second part. What do you remember from your 20th win that season? [Herbert won the final game of the regular season, beating Bill Stafford and the Yankees, 8-4, in New York on Sept. 30, 1962.]

I remember that I didn’t pitch very well that day. Lopez took me out after five innings or so. I gave up three or four runs. Al said to me, “You’re horseshit today, you’re lucky. Go take a shower.” We were able to win the game, though.

That offseason, you had a little trouble coming to terms on a contract, didn’t you?

I had been in the major leagues 12 years, just won 20 games, and was making $24,000. Ed Short was the Sox GM, and he offered me a deal with only a $2,000 raise. I didn’t think that was fair, and held out for two weeks. Ed and I finally agreed on a deal worth $28,000.

As a reward, you were named the Opening Day starter in 1963, back in your hometown of Detroit against your former team, the Tigers. Things didn’t go very well for you, as you lasted less than two innings, allowing four runs. [The White Sox would come back to win, 7-5, thanks to Pete Ward’s late, three-run home run.] Was it just one of those days, or did coming off 20 wins and the holdout put more pressure on you?

No, but the weather was really bad. When we’d play Detroit early in the season the weather was always miserable. A lot of times, it snowed. In those conditions, it’s just hard to grip the ball, to get any type of feel for it.

Despite that Opening Day, you put together one of the most incredible streaks in baseball history when you tossed four straight shutouts from April 18 through May 14 and had a streak of 38 straight scoreless innings. How does a pitcher do something like that? It certainly can’t be all luck. [Ray started his incredible streak in his next start after Opening Day: On April 18 he beat Kansas City, 3-0, allowing three hits. On May 1, he beat Baltimore, 7-0, allowing four hits. May 9 saw Ray beat New York, 2-0, allowing two hits, and on May 14, Ray took out Detroit, 3-0, allowing six hits. He threw four straight complete games, garnering four straight shutouts, and only allowed 15 hits in 36 innings of work!]

Sometimes you get in that groove where you just don’t make any bad pitches. You seem to get all the breaks, the guys behind you make all the plays, and the fact that it was earlier in the season helped. Hitters always start the year behind the pitchers, and it takes them awhile to catch up. Early, they just aren’t that strong.

Do you remember how the shutout streak ended?

We were in Baltimore, and the Orioles catcher hit a disputed home run. I say disputed because in those days Baltimore had a metal railing that ran across the top of the left-field fence to prevent fans from falling over on to the field. The bar was held up by concrete posts, so there were gaps between the top of the wall and the rail itself. Our left fielder swore that the ball went through the gap between the wall and the railing into the seats. That should have been a ground-rule double, but the umpire didn’t see it that way. [The game was played on May 19, and catcher John Orsino led off the third inning with that home run. The Sox left fielder was Dave Nicholson. Herbert would pitch 8 2⁄3 innings that day, giving up three runs in a game the Sox would win, 4-3, in 11 innings.]

Mark Liptak You won 13 games that year for the 94-win White Sox, and seven of them were by shutout to lead the league. What was the difference between you winning 20 games in 62 and 13 in 63?

Ray Herbert Sometimes it’s just a case of not getting runs that day. It happens.

You had been averaging around 30 starts a season until 1964, when you only started 19 games, winning six. Were you hurt at all?

I was on the disabled list for over a month. I got hurt batting in Cleveland. I started swinging at an inside pitch and saw that it was going to hit me, so I pulled back and turned my right arm as I did so. The weight of the bat pulled my elbow back; it snapped it, and I hurt the muscle around it. It never really healed properly, and led to my being traded to Philadelphia.

I actually went out and pitched the next inning, but it was hurting, and when I got back in the dugout I told Al [Lopez] that I was hurt. Al looked at me and said, “What do you mean, you’re hurt? You threw fine the last inning.” I said the arm was hurting me and that I needed to be taken out. I guess Al thought I was jaking it, trying to get out of the game. Why he would think that after I spent 13 years in the major leagues I don’t know, but he took me out, the trainer looked at me and it didn’t seem to be too bad.

I went to bed that night and got up the next day and had trouble raising my arm. Even worse was the way my arm looked. I got dressed, went to the stadium and saw Al in the locker room. He asked me, “How’s your arm?” I got my shirt off and said, “What do you think?”

Al looked at me and said, “Jesus ... you need to see a doctor!” My arm was purple from the elbow all the way down to the wrist! I broke some blood vessels, along with injuring the muscle around the elbow when my arm jerked back getting away from that inside pitch.”

The 1964 season was a bittersweet one for the Sox. They won 98 games and lost the pennant by one game to the Yankees. What were your recollections of that season, especially after the final game when the realization set in that the Sox barely missed a trip to the World Series?

We knew we had to keep winning, but also we knew the Yankees had to lose. During our game, we saw the score of the Yankee game; they had a big lead, and we knew that we just weren’t going to win it. The team had a great year, but there wasn’t a lot of celebrating in the locker room afterwards. As for me, I didn’t feel I was that involved with the year, because I had gotten hurt. [The Sox finished 1964 by winning their last nine in a row, closing the season out at home beating Kansas City, 6-0, for their 98th win. New York, however, had built up such a lead down the final two weeks that when they beat Cleveland, 8-3, on the final Saturday, they clinched the pennant. The Yankees lost the last day, 2-1, to Cleveland, making the final margin a single game.]

You played for Al Lopez. What was he like as a manager?

Al was a top man who really knew baseball and baseball strategy, but he was hard to play for. If you did one thing wrong, you were in his doghouse. Some guys, like Luis Aparicio, never had any trouble with him; other guys, like Jim Landis, had a lot of trouble with Al. I already told you how he reacted when I hurt my arm, but I remember another story of how he embarrassed Floyd Robinson.

We were at home on a Saturday afternoon. It was a national TV game, and I think it was 1963. Floyd was up in the first inning, and he hit a little pop-up. He ran about halfway down the line, then slowed up as the infielder caught the ball. Jim [Landis] brought Floyd’s glove out to him in the outfield, and they started warming up between innings. Lopez didn’t like the fact that Floyd didn’t run the ball out the entire way, so while they are in the outfield, Al turns to one of the guys on the bench and says, “You go in for Robinson.” The kid ran out there with his glove. Floyd had his back turned so he never saw the guy, and didn’t know what was going on. The kid must have said something like, “I’m in for you.” Floyd went back to the dugout. Lopez looked at him and said, “I see you don’t want to play today, so you can have a seat on the bench.” Floyd didn’t move or say anything the rest of the day.

Did Al get involved in the pitching aspects of the game, or did he leave you guys alone? Did he ever call any pitches, for example?

Al usually didn’t do things like that. Once in a while he’d call a pitch. I remember one time we were facing the Yankees in 1961, when Roger Maris had that great season. I had a lot of success with Roger by pitching him down and away. This day Al asks me, “How are you pitching Maris?” and I said, “Down and away.” Al said, “This time, I want you to throw him inside stuff.” I said OK, although I thought it was a mistake. Maris hit the pitch into the upper deck. I went into the dugout, looked at Al and said, “Do you still want me to pitch him inside?”

In my interview with J.C. Martin, I asked him to tell me about the pitchers that he caught, here’s what he said about you, “Ray was a good pitcher. He had a nice curveball, good cutter. He wasn’t overpowering. He made you hit the ball, usually on the ground.” I’d like to turn the tables and ask you to tell me a little about the three catchers who caught you in your days with the Sox. What kind of catchers were they?

Sherm Lollar was the “old man,” he knew everything. He’d been around the league long enough to know how to pitch to the hitters. Sherm was a guy who was always ready to help you. He’d come out and talk to you and remind you of things. He’d know if you were dropping your arm, or weren’t striding properly on your pitches.

J.C. Martin, at first he wasn’t that sharp, because he simply hadn’t played enough. Sherm would usually catch 120-130 games a year. The only time J.C. and Cam [Carreon] would play was in the second game of a doubleheader, or if a day game followed a night game. J.C. learned, and he was a great guy to have on the team.

Cam Carreon, like J.C. he didn’t play much, so he didn’t know the hitters. He’d sometimes call the wrong pitch, the guy would hit it, and Cam would wind up in Al’s doghouse.

In your days with the Sox you weren’t a bad hitter. You had five home runs and 47 hits. You took pride in your hitting, didn’t you?

I took my batting practice early on game day. They wouldn’t kick me out of the cages, and I’d get my swings in. I won a few games with my hitting. I remember a game I won, 3-2, where I drove in two runs. Another time I remember hitting a home run off Ralph Terry of the Yankees to win a game.

And I remember the time I called a home run. It was in 1962, on the day I won my 19th game. We were in Boston, it was late in the season, we were up by four or five runs late in the game, and the Red Sox brought in a kid to pitch. He may have been making his major league debut, I don’t remember. In those days when the pitcher was going to lead off an inning, the leadoff man would bring his bat to home plate. That way the pitcher could get a minute or two more of rest in the dugout. I go out there, and Jim [Landis] is waiting for me. I asked Jim if he knew anything about this guy, what he threw and so on. Jim didn’t. I said to Jim, “This kid don’t know me, he’s going to think this is just a pitcher, and throw me a fastball. I’m going to hit it out of the park.” Sure enough, the guy throws me a straight, batting practice fastball and I hit it over the wall in left field. When I get to home plate, Jim turns his back on me! I went into the dugout and all the guys turned their backs on me! Jim must have told them what I said and they were giving me the business.” [Laughing] [That game was played on Sept. 26, 1962, with the White Sox winning, 9-3. Herbert hit his home run in the ninth inning, off of Hal Kolstad.]

Mark Liptak After the ’64 season you were traded to Philadelphia, where you finished your career. What did you do after baseball?

Ray Herbert I stayed in baseball. I was the home batting practice pitcher for the Tigers from 1967 through 1992. I went to the World Series with them in 1968 and 1984, and went to the league playoffs as well.

Ray, can you sum up your time with the White Sox?

It was the highlight, the peak of my career. I enjoyed Chicago greatly. That’s the main reason why I go back as often as I do.