Dudley and sailing evermore

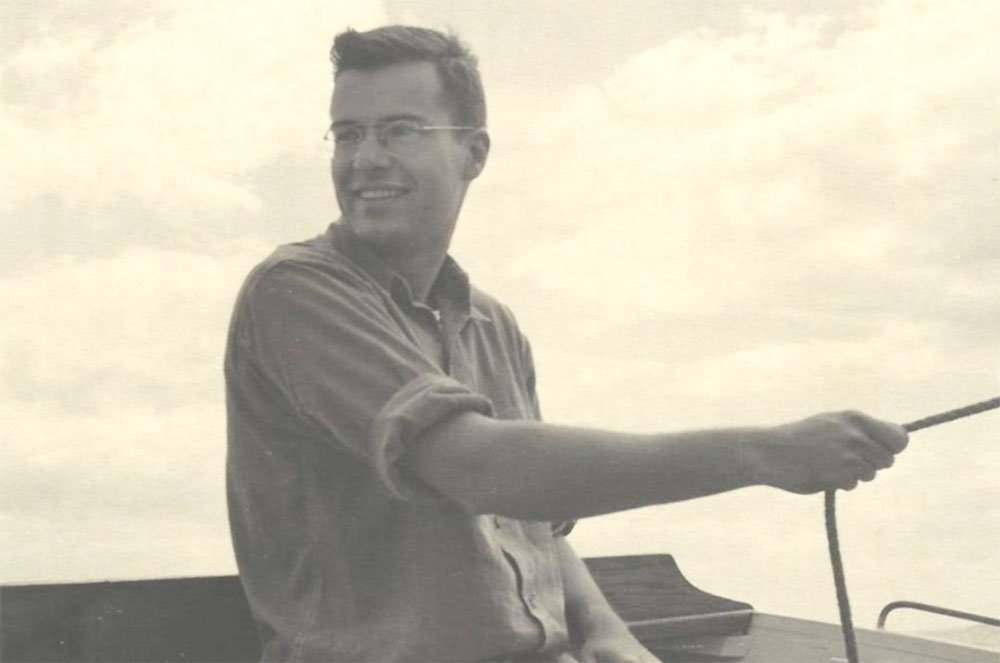

A hand on the tiller, a hand on the sheet: A young Tom Dudley engaged in one of his favorite pastimes, sailing. Photo courtesy Tom Dudley

By Tom Dudley

For Points East

This posthumously published love letter from the late Tom Dudley – to the sailing life, and to the woman who also wished to enjoy it with him – is the first in a series of lively reminiscences to be published in Points East over the coming months. Thomas Minot Dudley, of Durham, N.H., died at the age of 83 the day after Christmas 2013. Tom’s wife, Dudley Webster Dudley, a former New Hampshire state representative, believes that he would have wanted to share his distinctly New England memories (with some Caribbean ones thrown in) with Points East readers. We begin this lifelong narrative in 1954, when a summer job morphs into the encounter of a lifetime.

Bob and Polly Webster managed the Lake Sunapee Yacht Club, in Sunapee, N.H., and I waited on tables in the bar. Their daughter, Dudley, was a swimming instructor, and her brother, Gideon, was maintaining the tennis court. I became friendly with the Websters – he taught English at UNH and she was a writer – and they were, for me, the most interesting and entertaining people the club had seen for many moons.

For Bob and Polly, this was a summer job, with no future and little gratitude from the members, who, for the most part, viewed them as servants. This all made a big hit with me, so I decided I should meet their daughter, who would have to be equally intriguing and another breath of fresh air. Little did I know.

Our first meeting was a life-altering moment, for me. We married in 1956, had two girls, and now have a granddaughter – all of them exceptional. With my passion redirected, sailing and racing continued, but without the old fire. Dudley and I raced together one season, with modest results, achieved in the face of the various charms and distractions she presented: More than a fair trade.

In the fall of 1955, I was astonished to get a phone call from an older acquaintance in Concord, Dick Ward. He sailed a fat Alden Traveler, a 33-foot cutter named Reward, out of Marblehead. He invited me to join him and his friend Bill Shreve on a weekend run from Marblehead to Rockport, on Cape Ann, on the following Saturday, and return on Sunday. Just cruising. So, for two days, I joined people who sailed purely for the love of it.

I knew Dick only by reputation, and was totally surprised and pleased by the call and the experience . . . my first on a pure, leisurely cruising boat. They were both great friends, who had sailed together during World War II on a schooner crammed with listening devices and radio gear. They listened for Nazi submarines off the East Coast. Their boat was wood and sailed quietly, so it was not easily detected, but it was high-risk work. Rifle fire alone could have sunk them in minutes.

I loved their stories and their easy ways on the boat. I took note of their small heating stove, and have used a duplicate in our boats since 1977. This opened the door to coastal cruising for me, and the joys promised us by Kenneth Grahame in “The Wind in the Willows.”

If you are granted three wishes, make this the first: Dick Ward and Eleanor invited me to join them on Reward for a run out to Nantucket and return. We sailed in company with another cruiser, who spent the entire trip belowdecks calling friends on his radio while his hired captain ran the boat. Dudley had come to Marblehead to see me off, but the Wards kindly invited her, too, and Eleanor promised to chaperone us from behind the door to the forward berths. She was the best.

It was all perfect – hormones raging at the Grey Ledge Inn at Marblehead and throughout the voyage – ending with a thunder squall on return.

After our marriage Dudley and I moved to Kittery Point, Maine. We came to know Pepperrell Cove (where we’ve anchored some boat for 50 years), Brave Boat Harbor (by skiff), and Little Harbor at New Castle. And we bade farewell to Lake Sunapee and other lakes. The horizon is one powerful magnet, so we’ve gone to sea ever since, each season, if only to the Isles of Shoals, an hour-and-a-half away by sail.

The sailboat fleet at Kittery Point was MerryMacs, plywood, hard-chined 14-foot catboats with daggerboards. We met Joe Badger, who was promoting them for a racing fleet and for teaching sailing to kids. Ned McIntosh, of Dover, N.H., designed and built them, sometimes racing with us. He was already a local legend, having salvaged his own 32-foot boat, Star Crest, and sailed her to the Galapagos and back.

This all connected us eventually with Dick Johns, Harry Hall, Peter Beierl, Bill Stevenson, and others who gathered for races and picnics at Kittery and Great Bay, up the Piscataqua River. I taught sailing to Bensons, Crowls, Kehls, Hubbards, and other children in Pepperrell Cove. This boat was really all anyone needed, but we pushed on to grander models.

In 1958, Dudley and I bought a seagoing motorsailer from Donald Wilson of Dennis, Mass., on the Cape. She was 19 feet long, lapstrake, with a one-cylinder gas engine, two kerosene stoves, two berths. She had no head, no sink, no water tanks, no electronics, and inside lead ballast that I installed after Horace Mitchell (publisher of Kittery’s only newspaper) melted down lead pipe, flashing, weights, and other scrap lead in the furnace of his linotype machine, and then poured it into forms I’d made.

We named her Viking, and sailed her for short runs to York, Rye, Isles of Shoals, and Little Harbor. She had a lovely seagoing look: plumb bow, flush deck, wineglass transom, no varnish, and outboard rudder. Dudley’s criteria (minimal) for any cruising boat were standing headroom, enclosed head, galley with sink and icebox, and four or more berths. We had squatting headroom, cedar bucket and Clorox, two primus kerosene stoves, two glass bottles of water, a portable cooler, and two berths. Entering the berths was an acrobatic process, requiring a horizontal position, feet first, much like easing a loaf into a very shallow oven. But we had four-inch foam rubber cushions and slept well, being exhausted by this process.

My criteria were: She floats; she sails.

Her sails were OK, but she was tired. The engine was a shaker, which had weakened the structure astern. When we launched her, she leaked, so I spent the first night aboard with my arm in the bilge to gauge when I should start to pump. Our pump was a tall galvanized pipe with a funnel top, wood plunger, and leather flapper valve and sucker cup. It reached above the main hatch, so we could bail right out onto the deck. With a three-inch diameter, it could move gallons in no time, but it took some force. She sailed well enough to get us home, but it wore me out with trying to keep her afloat. We finally gave up and moved to another material and design.

In 1960, fiberglass was making boats economical, seaworthy and low-maintenance. It changed the game forever. Wood persists and commands respect, but plastic rules. Wood has great beauty; fiberglass has practicality and strength. Hunt Walton, our friend and neighbor in Kittery, located a Pearson 221⁄2-foot Electra, which had been a demonstrator in Marblehead. Dick Ward was the agent, and he said this boat had broken loose and gone ashore in a recent hurricane. Hunt and I went down to examine her, and I found five or six quarter-inch spots on one side where the gelcoat had broken away, leaving the raw fiberglass exposed – nothing more. A miracle. A wood boat would have lost planks and possibly frames.

Hunt bought the boat, and he and I later sailed her to Kittery on a perfect October day, spending about an hour in the sun in Ipswich Bay when the wind left us, then changed direction to southeast. Right On took good care of us for the next 161⁄2 years, thanks to Hunt’s great generosity and a succession of co-owners with me.

Aircraft engineers designed and built marvelous plastic boats, but it took decades for builders to learn how to finish anything off. Fiberglass edges stuck out everywhere, and were ugly, abrasive and even dangerous. Owners back then broke skin and bones on these edges, but the payoff in easy care and sailing performance was immense.

The Electra was a winner. I sailed my early races solo, until George Pitts protested me after one win because the rules specified two people per boat. He never pursued it, but I sailed at least one race with our infant daughter, Morgan, in a basket, sleeping quietly throughout. After that, our great friend Bill O’Connor, from New Castle, sailed with me, and we had many wins. Ian Bastelier from New Castle eventually bought this boat and took me along to sail it in races. After his first effort failed to get results, he let me do the sailing, starting in the middle of the race. We still won, even then.

Auxiliary engines are a trial. Gas-powered units purr, but all their electrical components corrode in the salty surroundings and closed compartments. Diesels pound and can be hand-started, but they don’t get enough exercise. Our Electra’s Sea-gull outboard was a jewel. It always started, rarely misfired, required little maintenance, and you could take it home in winter. Once, the gearbox failed to engage. I broke it down and removed the drive shaft, to discover that the stub emerging from the gears, and the cavity in the shaft which fit this stub, had become rounded off by corrosion. After merely turning the shaft end for end, so the un-corroded top portions did lock in, she worked as before, and she finished the season as usual.

Before this, Ian and I sailed his Rhodes 19 up to York, Maine, to swap it for a 17-foot O’Day Daysailer, as there was a fleet of them racing in Portsmouth. On our return to Kittery, after noon, we capsized outside York. Together we could not right her after the mast filled with water. We would surely have died in the 58-degree water had a lobsterman not returned from his traps later than usual. He helped us right her, and took us to hot showers in York. It was a very close thing. No one else was boating that day.

One day, Dudley and I took a pleasure sail with our friends the Hapgoods, along with their daughter and our two daughters. All three children had life vests on. Returning in very light winds on that hot day, Marilyn suddenly announced: “I think we’ve lost someone.” Sure enough, our daughter Becky, 3, was missing from the foredeck. Dropping the tiller and lurching over the rail, I found her alongside, life jacket firmly in place, and swimming for all she was worth to keep up. It was a heart-stopping and life-and-death moment. Trying to lift her by the life vest failed and drove her head under water. In desperation, seeing my beautiful, happy girl on the edge of breaking free and drifting astern, I grabbed a handful of her hair and brought her aboard. In that moment, everything changed. No boat experience could ever touch the horror of that one. It wakes me at night often, ever since, and permits no sleep. The guilt, shattered self-confidence, remorse over the pain and trauma she experienced, and sure knowledge of my sole responsibility are still alive and well. But so is she, nearing age 50, married, and the lone scholar of us all.

We were moving so gently in that light air, and full sunlight, that she appeared to have dropped off to sleep and rolled off the deck without a sound. She was very stoic, and also made no sound until we rode home, but a large patch of her long, dark hair fell out leaving a bare spot, which finally regrew.

We spent many years sailing with children, and have loved their company, always, and watched them constantly. But the thought that we might have sailed away from Becky, and finally seen her alone in the sea behind us, haunts me still.

These days, she generally stays off boats unless there is a ladder up onto them from the ground. However, she told us of a day in Seattle when friends asked her to go for a sail, and she accepted – only to discover when they got under way that she was the only experienced sailor onboard. They all got home, and I took great comfort in her story.

But the dark corner of memory of her near loss sailed on with me. My mantra became, sail with someone who knows much more than you; it will make you humble and hungry for more information. This is one of the great joys of being ignorant. Smarter is usually better.

Sailing was Tom’s lifelong passion, spanning 74 years, beginning with his first lesson at Camp Chewonki in Wiscasset, Maine, and summers spent sailing catboats on Nantucket. From racing his Star boat Princess on Lake Sunapee with his brother Dick in the 1950s; to cruising Maine and the rest of the New England coast on his boats Viking, Right On, Celia and Wild Hunter; to offshore cruises in the North and South Atlantic – from the 1960s every year through the summer of 2013 – Tom cherished time spent on the water in good company.

The post Dudley and sailing evermore appeared first on Points East Magazine.