Confession: The Olympics Made Me Want to Train (Again)

1. The wannabe

I am not a competition climber, and I never really was, but I did go through a phase—in college—when I wanted to be.

This was in 2010, back when competitions were considered mildly fringe in the American climbing scene, popular among kids whose parents needed daycare and Europeans whose sponsors cared. Sure, famous American climbers like Daniel Woods and Alex Puccio occasionally dabbled on the World Cup bouldering circuit, but their seemingly haphazard success underscored the fact that elite outdoor performance (for which Woods and Puccio were famous) didn’t correlate with whatever comps were testing for. So my friends and I instead imitated other American heroes—notably climbers like Dave Graham, Joe Kinder, and Chris Sharma—who viewed indoor climbing purely as training for audacious outdoor goals. When we went to local comps it was because they were more like parties than serious events designed to help people prove their relative worth. And we would skip those comps if the northern New England winter (RIP) let us get an even mediocre session on real rock.

All this briefly changed for me in September 2010, when I finally got my hands on a DVD of Big Up Productions’s 2009 film Progression. I’d bought it to see Chris Sharma on Jumbo Love and Daniel Woods and Paul Robinson smashing Rocklands, but I found myself instead enthralled by the Basque competition climber Patxi Usobiaga, who had utterly subordinated normal human concerns like fun or friends or real rock goals to a single-minded and almost religious training regimen that was designed to make him “the best.”

Now, I didn’t really believe all that macho talk about becoming “the best,” because even then I felt that performing well on a given day, in a given competition, didn’t compare to the kind of lasting accomplishments that my first-ascenting heroes made on the rock. Nor did I truly expect—at 22 years old, having climbed a few soft V9s and some 5.13+s—to suddenly become a world-class climber. But I did fall heavily for Usobiaga’s example of what it looked like to be 100 percent committed to a climbing goal. And I sensed (perhaps erroneously) that, for Usobiaga, the thousands of daily moves and ridiculous number of pullups were only nominally justified by the competitions themselves—that the real point of the training was the sense of purpose it gave him, the satisfied exhaustion engraved in his cheekbones, the virtuous dedication in his ferocious black eyes. I wanted that. But I also, admittedly, did let some fantastical thinking come into play—a secret hope that, even though I had never demonstrated insane natural climbing talent, perhaps it was there, sleeping inside me, simply waiting for an act of superhuman effort to awaken it.

So I turned to my friend Scottie—an engineering type who was obsessed with training and whose eyes, watching Progression, had slowly lit up with excitement, as if he’d finally found the answer to the great secret for which he long been searching—and said, “Do you think you could coach me to do that sort of thing?”

2. Progression

We didn’t know about periodized training or antagonist training or training blocks. We didn’t know about progressive overload or no-hangs or energy systems or strength training or fingerboard best practices. Instead, we opted—or I opted, under Scottie’s vague direction—for what can only be described as a quantity-over-quality approach. I rejiggered my course schedule so that I had mornings off four days per week, which allowed me to train in the gym when it was empty. Then I proceeded to climb or train five to six days per week, for four to six hours per day, often—because I didn’t know better—working on everything in the same session. After warming up, I’d campus board and hangboard (without adding weight because I was convinced I’d injure myself if I did) before doing board-style boulders, and power-endurance circuits, and long endurance, and an hour or two of pull-ups and core. (Mobility? Rest? Antagonist training? Nah.)

Because comps were still nominally a goal, I jittered my way through two very local competitions that winter—one at nearby Dartmouth College, one at my local gym in Burlington—and came away from them understanding two things. First, that instead of lighting up a “competitive instinct,” competitions tended instead to make me fearful of my audience’s gaze—convinced that everyone would immediately understand that I was weaker than all the other competitors and therefore, by extension, irrelevant and dismissible and doomed. Second, despite my training, I was weaker than most of the people I knew, in part because I hung out with people like Jake List, Brian Bittner, and Andrew Palmer, who were some of the strongest climbers in New England back then—each of them having already climbed far harder, as it turns out, than I ever will.

So the idea that I was training for comps pretty quickly went out the window. But I kept training. Because I vaguely wanted to get better. And because it felt good to have some sort of focus or direction to my days. And because I respected people who were better than me—and I wanted to respect myself.

I wasn’t the only climber in my gym training hard and consistently at Petra Cliffs those days. The aforementioned Brian Bittner had teamed up with a friend named Matt McCormack, and they were working out together. I remember them shaking their heads at my “plan,” convinced I was overtraining, while I shook my head at them, convinced they were not trying hard enough to deserve results. But they were right, of course. And instead of seeing gains, I was, by mid-winter, getting worse.

Nowadays, training regressions are pretty commonly understood; coaches and climbers know that there’ll come a point, late in a hard training block, when you begin to feel worse, but that pushing through that is part of the process (as is taking a deload period). But Scottie and I didn’t know to expect this, so I despaired, and it got personal. I began to think that self-improvement wasn’t actually possible for me—that effort alone could not transform me into something tolerable and new.

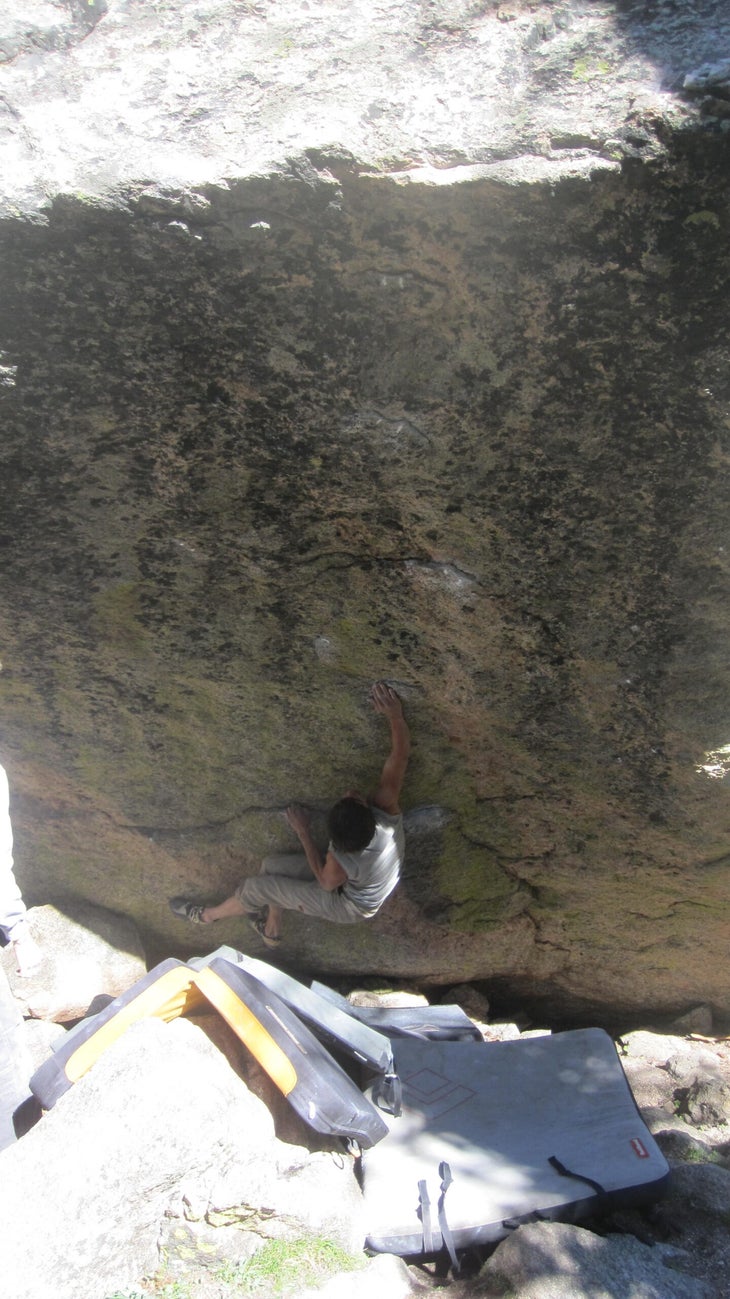

Things came to a head for me, in late April or early May 2011, after about nine months of this idiocy, when Bittner and I (and a few other friends) went on a day trip to Great Barrington, Massachusetts. I was hoping to climb a classic New England V11 called Something from Nothing, and I got to watch Bittner (who’d already climbed far harder) send in just a matter of tries before turning his attention to its V13 neighbor. But I could not even do Something from Nothing’s crux move in isolation. And when I finally gave up, I failed not on the neighboring V13, but on a nearby V8. Almost overnight, I decided that climbing wasn’t a sustainable scaffold for my dreams, and I began taking steps toward what turned into my writing career.

But something strange happened when—after two months of rest—I started heading to the boulders to blow off steam: I almost immediately sent my first V10s and V11s.

Now, if I was a smarter or more patient person, I might have understood that training hard, then resting, delivers results that training hard alone cannot. But since I had so completely abandoned my climbing goals and was so focused on overtraining for my new writing career, I didn’t pause to think about how I’d suddenly moved up two grades. Nor did I bother to dive into a new training cycle. Instead, I spent the next 12 years happily maxing out around V10 or V11, climbing only when the temps were good and I had the time.

It was only two years ago, when a series of injuries dropped my level far below even my 2010 plateau, that I looked back and realized that all the haphazard overtraining I’d done while pretending to be Patxi Usobiaga had actually kinda worked. But by then I was too injured, and my writing career was too busy, and I was too lazy to apply that lesson to my older (and hopefully wiser) self. Instead, I kept on casually climbing whenever I could, getting a few sessions per week on my home wall when I was busy, heading outside when I had a spare afternoon.

3. Enter the Olympics

As an editor at Climbing, I spent much of last week waking up each morning from Monday through Saturday at 3:30 a.m. ET and watching the Olympic Sport Climbing events, after which I’d spend the rest of the day writing and editing about the event or researching the athletes and their training plans, trying to contextualize what was happening for our audience. In the process, I learned that the Men’s Combined Boulder & Lead gold medalist, Toby Roberts, spent the last six years training specifically for the Paris Olympics. And that Jesse Grupper, who had an unfortunate Olympic showing but who is nonetheless ridiculously talented, can climb up a V12, down a V6, and up a V10, on the Tension Board 2 when set at 40 degrees. After soaking in such content, I suppose I shouldn’t have been surprised when, on Saturday morning, after watching Janja Garnbret win the women’s Combined final, I blinked and found myself training my shrunken antagonist muscles on my office floor. Or that, at around 9:00 p.m. on Sunday night, I found myself doing a post-toothbrush no-hang session on the hangboard I’ve spent the last 14 years coming up with excuses not to use.

I certainly don’t want to do competitions. Indeed, I’ve developed complicated feelings about how their expanding role in the sport is changing what it means (and how it feels) to be a professional athlete. But competitions have—for a second time—made me excited to push myself, to devote myself to a climbing goal, to see how my body might respond if I committed to even 10 percent of the weekly training that each of these Olympic athletes did. Can I get back to, or even surpass, my pre-2022 fitness? And, if so, can I take it further and level up for the first time since 2011?

The logical part of my brain doubts it. (I’m still pretty injured.) But the optimist in me has been pouring through a variety of training articles, like this Kevin Corrigan classic that answers a version of the same question I’ve been asking myself: What Happens When a 5.9 Climber Starts Training Like a Pro?

I’ll let you know how it goes.

The post Confession: The Olympics Made Me Want to Train (Again) appeared first on Climbing.