My Rocky Return to Climbing After a Life-Changing Accident

This story, originally titled “Terror of Turning a Corner,” appeared in our 2024 print edition of Ascent. You can buy a copy of the magazine here.

December 1, 2023. Olivia and I are at the base of a nearly two-mile-long sandstone wall in Suesca, just north of Bogotá, Colombia, when my heart rate suddenly becomes freaky high. This is partially because I have had three cups of coffee and partially because we just scampered up a climber’s trail that was steep and messy with vines. It is partially because Olivia and I have just realized we’ve never actually climbed together before, and now I am nervous that she’ll soon learn something about me she won’t like.

But the terrible whap in my chest is mostly, mortifyingly, because of my brain.

In 2019, in the weeks before the accident, I rode my bike about 80 miles a day. Because I had what felt like superhuman fitness, I figured the bike crash would put me out for about a week. It was an ordinary accident; I did not think it would keep me from having an ordinary life.

I had been told it was only a minor concussion. But, as at least 30 percent of people with minor brain trauma are, I was eventually diagnosed with post-concussion syndrome. Instead of getting better, I got steadily worse. Like the blink of an eye, years went by.

Most mornings, I would wake startled, out of breath, thinking, Where am I, or, Oh my god, that feeling in my skull hurts so fucking much I cannot be awake through this, please, god, make it stop, let me fall back to sleep. I am begging you, please. I whittled away at the richness of my life. I learned to avoid bright lights, loud noises, or any situation in which I might be provoked. None of it was enough to make my body any better behaved. I gave up on greatness. I tried to settle into my small life.

In 2023, when things began to mellow out, I was surprised. The pain lifted; the days began to recalcify. Mellow is a miracle when you’ve been sick for a long time. An absence of pain starts to feel how I imagine Olympic athletes feel all the time—invincible, like their bodies are made of lava or light. Giddy with possibility, I traveled to California in the spring and Alaska in the summer, all of it better than I had bargained for. It was enough to make me believe I was standing on the precipice of a new life.

One day late that summer, I opened Airbnb at random. The first listing was for a cabin at the base of a cliff in Colombia, and that was that: I was going to go there to climb.

Climbing used to be the only thing in my life I didn’t question. I just started one winter, when I was 23 and restless, and from then on, that was how I organized my life. Why, or whether, I liked climbing felt irrelevant. It filled me with an unblinking feeling, the way I imagine people with good parents or healthy marriages feel. I desperately wanted that feeling back.

It had been easy to convince Olivia to come with me to Suesca. She had just quit her job and had a fizzing but unspecific desire to get away. It wasn’t until we were well into trip planning that I told her I hadn’t climbed outdoors in months. “Me neither!” she had replied, her voice unbelievably sunny over the phone. And then I told her that I had only climbed twice in the gym since tearing my rotator cuff in three places that May.

“Does it still hurt when you climb?” Olivia asked. I could not tell her that it hurt too much for me to have done any climbing. I wanted, badly, to want to climb. “I’m not sure,” I lied.

I did know that several years of pent-up desire, mixed with my intractable recklessness, was a heady drug. I was hungry for endurable pain, or ascension, or both. The first Friday in September, I drove three hours from Portland to Mount Rainier and ran 13 miles to link up three summits, even though I hadn’t run in months. And then, the very next day—my legs barely sore, my mind blissfully clear—I went to my favorite trail and set a PR on my 10K time, as though the only thing preventing me from triumph was my belief that I was still unwell.

I slept for 14 hours that night. In the morning, I was too tired to speak. The next day, I was unable to focus my eyes. A clenched-fist feeling arrived in my stomach so bad I couldn’t eat without passing out. As the color drained from the kitchen and my head found the dirty tile floor, I thought, This can’t be real.

More than a year had passed since I last had so many terrible feelings stack up at once—long enough to let me believe this could never happen again. My relapse felt like somebody outside of me, somebody in control, had shoved a list of every way my body could feel awful under my nose. You wouldn’t! I imagined screaming at them. Wanna bet? I imagined them saying back.

Curled up under blankets, nauseous and shivering in the 80-degree autumn heat, I texted Olivia to ask whether she thought we should bring a trad rack or find a place to rent a rope.

I thought back to the time, five months after my accident and just a couple of months after we’d met, when Olivia had driven me to the emergency room because my concussion symptoms had intensified so rapidly that she thought I was having a stroke. Or how we’d broken our respective early-pandemic isolations so I could cry on her couch, leaving me with an almost disgustingly visceral memory of her hand stroking my hair while I got snot on her shoulder—the only time, in over four years of illness, I let someone hold me while I cried.

Despite all this, I could not bear to tell Olivia—or perhaps it was a refusal to admit to myself—that my symptoms were back. I waited until three weeks before our flights to tell her how sick I’d become.

“Whatever you want to do, I trust you,” Olivia said, without an edge of anger in her voice. If we could not climb well, we could at least climb something easy; failing that, she said, she would be content to loll about and drink wine. This would have been a good backup plan if our trip was for one weekend and not an entire month.

“Let’s just say it’ll be fine and plan the trip like I’m normal,” I finally told her, glad she couldn’t see my grimace through the phone.

Autumn ended. After a hellish month, my mysterious symptoms disappeared as quickly as they arrived.

Standing level with the tops of the quavering eucalyptus grove at the base of La Nariz, I look down at the Bogotá River, murky water churning beneath the trees. Olivia begins to unspool the rope and organize the equipment. Already, she has been figuring out how to hail the right buses and order all my meals. I do not like how ashamed this makes me feel. I sense that she knew before I did that she would be the one in charge here, but I also know she does not hate me for it, not in the way that I hate me for it.

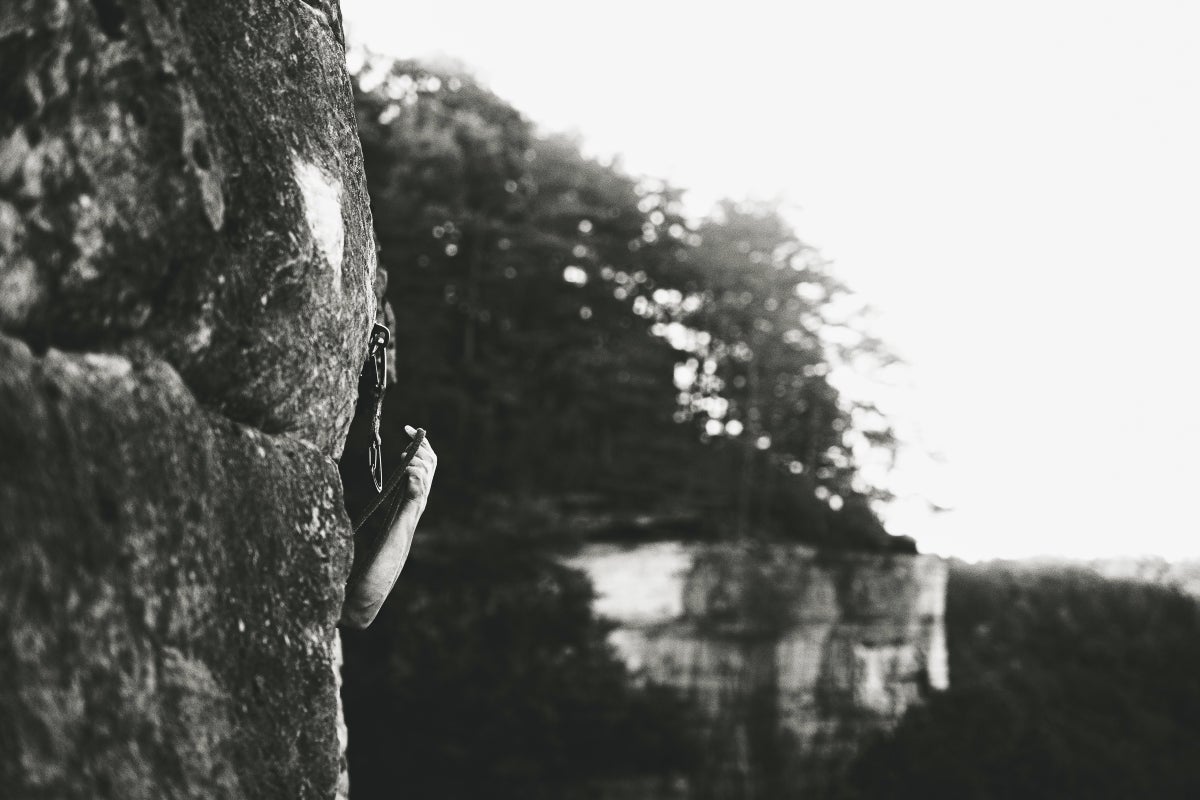

I jab two of my fingers into the fleshy concave of my neck. To feel less useless while I check and recheck my pulse, I tell her my opinions about the scenery. The bromeliad roots, draped in huge clumps along the cliff band, look like deflated ghosts. The whole place is simultaneously tropical, cheery, and something a few shades off of doomed.

“If at some point you want to practice leading again, we can do that,” Olivia says, smiling as she clips gear onto her harness. Discussing the trip, I never said, I am not going to lead a single pitch, but as soon as she implies it, I feel it becoming true.

Olivia dances up a route that is either a guidebook 5.5 or a Mountain Project 5.7, and then I tie in to toprope. The rock is full of huecos, lined like ladder rungs up the bulging arête. But trying to force my muscles, tendons, and bones to coordinate feels like the bodily equivalent of conjuring the 20 words in Italian I learned a decade ago. My hands flap about, feeling every possible hold as I shop for the best option; all of them are massive and fine. I am thrilled and embarrassed and want to bury my head in the sand. When I reach for a jug, a beetle with a large pincer on its rump jumps beneath my fingers. I hold my breath for a moment, expecting him to bite, but all he does is scuttle a few inches to the side.

Halfway up the 60-foot route, I am seized with panic at how obviously I do not belong—on this climb, in this country, with a harness or a rope anywhere near my body. I do not know if there is a hospital in this village. I do not know if Colombia uses the number 911. A better person would have looked all of this up. I tense so hard at this realization I pull a muscle in my neck. The pain is wretched, but part of me feels glad. There is something exquisite just beneath the sharpness of my hatred—of my weaknesses, my hesitancy, my limitations, my disbelief. I do not want to banish these feelings; I want to hold them close, as though they’re the last tatters of something precious I’ve lost.

I groan and flail and kick the wall, shouting down to Olivia, “I feel nervous!” using a silly tone of voice that I hope will make her laugh. “You’re doing great!” she hollers back. “I don’t believe you!” I shout. “You don’t have to believe me for it to be true,” she replies.

Eventually, my hands find the dusty, rounded ledge where this route ends and a different pitch begins. I trace my fingers across the ruddy, dried clay ringed around the glue-in anchor bolts, waiting until I remember how to tie out and thread the rope through the chains. A minute passes and then another while I wait for the knowledge to snap back like a rubber band. A bitter voice in my head—a staticky mash-up of doctors, of other climbing partners I once had and who have left—asks if what I’m doing is even real climbing, if this is really a climbing trip—if I am really someone that deserves to be trusted with Olivia’s life, or my own.

And then it happens: The memory unlocks, and I finally figure my shit out. I force a laugh while I clean the anchor. Before shouting down to Olivia that she can lower, I weight and unweight the rope half a dozen times.

At the base of the wall, hands shaking, I lie and say I loved it. “Let me know if you want me to clean the next one,” she says while she re-racks at the base of another route. “I really don’t mind climbing something twice.”

A month before traveling to Colombia, I saw Timmy O’Neill’s film Soundscape at the Banff Centre Mountain Film Festival. In the film, Timmy went up the Sierra’s Incredible Hulk with blind climber Erik Weihenmayer. I watched as they stood at the base, and Timmy showed Eric the beta by grabbing Eric’s hand in his own, tracing the line they were about to climb by reaching their interlaced fingers toward the top of the route. Climbing side by side, Timmy tap-tap-tapped his foot on the good holds to guide Eric via sound. Their bodies were so close they could have been playing Twister. It was so intimate it made me feel physically unwell to witness. At no point in the film does anyone try to prove that Eric belongs. This was staggering, excruciating to see. It stood out in neon contrast against the fact that I had let myself believe that I belonged nowhere, that the reason I stopped climbing outside after my accident had less to do with my physical limitations than it did with my inability to imagine that anyone would be careful with me while I fumbled through my fear.

Watching the film, I felt certain that Eric should be there on that climb. But having felt that does not make me feel any more strongly that I should now be here, flailing my way up these climbs. I had come to believe that I only deserved accommodations if I earned them through the force of my desire. Mediocrity, I had somehow learned, was not owed access. Eric’s right to accommodations had seemed so obvious; mine felt complicated by my laziness, by the confusing and unstable nature of my illness—by the impossibility of even claiming something like patience, kindness, or grace as an accommodation.

Before I’d fallen sick, my entire sense of self and belonging was tied up in the fact of my hardness and my ability to prove it to others. I believed wild landscapes were nothing more than testing grounds for my inner grit. Anything that revealed that the outdoors could mean something else to others—coming across a parking lot on a summit or stumbling down an elaborate stone ADA path in a national park—would frustrate me. This reaction should have exposed me to my foolishness, but cruelty seemed easier than inner change. When I got sick in 2019, this sentiment twisted in on itself and found a new target: me. I had to learn how to be a different person at the same time that I was learning how not to resent the fact of my difference. It took hundreds of attempts before I could request accommodations without projecting my self-loathing onto whomever I was asking for help.

It no longer feels difficult or confusing to me that people should have abundant access to whatever accommodations they need to do literally anything they want; these accommodations should be provided long before anybody needs to request them. And yet climbing—with its obsession with purity, its infighting about bolting and style—feels like an especially ill-suited space to insist that I belong. I have asked for accommodations in a courtroom, crowded theater, and even in bed with a first date. But at the base of that first route in Suesca I still catch myself thinking that maybe I should leave the climbing to people who can really climb.

Olivia doesn’t seem to give a shit how well I climb. Unlike me, she is satiated by the novelty of the squeaky birds and the early December heat. After we climb two more routes, she wanders off to a sun patch, swings her legs off the ledge’s edge, and closes her eyes. It is remarkable to behold someone so at peace when I feel on the brink of catastrophic disappointment. She is either totally self-actualized or putting on a very compelling act. Either way, I am relieved that I only have to endure my own scrutiny. While she nods silently into the breeze, I pace around beneath the eucalyptus trees, pick apart a piece of chorizo, and wish I hadn’t quit smoking cigarettes so I’d have something else to do with my hands. Eventually, she wanders over and reveals an iridescent green moth trapped between her fingers. She holds it gently, leaving her hands outstretched until the moth is ready to fly away.

On the second day, we go to an area where there is a 5.5 in a blocky corner with a wide hand crack that extends 50 feet up the wall. I surprise both of us by asking if I can lead it. My first piece is a nut. It pulls as soon as I’m above it. I have no idea whether this is because the crack is weird and flary or because it has been years since I’ve placed gear, and I no longer know how to do it. But I have the good sense that this question should wait to be riddled through until I have finished the climb. I get a few rattly cams in after that. I get scared, and then I get over it, and then I finish the route. A bird screams in the distance, its call ridiculous sounding, like this is the first time it has ever tried to sing. At the base, Olivia is beaming, her face all lit up around her smile. With a sports-dad level of pride, she asks if I also want to lead the next route. “Absolutely fucking not,” I laugh.

On the fourth day, we walk up a teetering trail to a ledge, ducking beneath the bromeliad roots, stumbling in our Birkenstocks along the six inches that separate the cliff and the abyss, to get up to the El Bong terrace where there’s a two-pitch 5.9 we were told we should try. We agree to each do the first pitch before committing to the second.

Ten feet off the start, Olivia pulls a roof and vanishes onto the other side, a rack of borrowed, ancient gear that’s been rewired with plastic fishing line tinkling at her waist. Ten minutes later, I glimpse her when she steps onto a faraway arête but lose sight again when she ducks into a chimney. She has long been out of earshot by the time the rope’s halfway mark wiggles toward my hands. My voice vanishes into the wind when I yell up that she’s got 15 feet and then five, and could she please just build an anchor and come down so we don’t run out of rope and need to do any shenanigans? She hears nothing and climbs on and on, but the rope stretch is enough that her toes touch when I lower her. “You’re going to love it,” she tells me while she pulls off her shoes.

But I’m spooked by the bouldery, committing moves and can barely pull the mantle to get off the ground. Something is wrong, I think, as I writhe my body up the dihedral, trying to remember which direction to angle my toes down into the crack. There is a sharp pain in my arm. I am just inventing excuses not to have to climb out of earshot where I’ll really be on my own, I think. Whining and grunting, I make a show of twisting my hands hard into the sandy crack. The pain is psychosomatic, I tell myself again. It is always psychosomatic. I am so goddamn weak. As I worm through the roof, my torso does some beached-whale thing, and I hope Olivia can no longer see me. Then, another roof. I shove my fist into the crack beneath it, which makes the pain become very, very loud. Hanging on the rope, I sputter, silently sob, and hate myself, all of which makes me suddenly want this.

The irrational rising of strength, the glaring desire that swallows up the possibility of having any extraneous thoughts, the propulsion I can feel in each of my cells—of course, this is what initially hooked me and what has, across the space of four lonely years, lured me back. A sensation of light that is also a lightness enters my body, and it feels for a moment as though my will has outmatched gravity at last. I pull the roof.

Past the crux, my concentration simmers. Suddenly, I am in so much pain that I throw up a little bit in my mouth.

Perched above the roof, I riddle over my next moves. OK, I concede to no one, so the injury is real. Whatever, I’ll take it. I lower and tell Olivia, tail between my legs, that she has to clean the route. She sees the tears in my eyes and rushes forward to comfort me, but I hold up a hand. “Do you want to take a second?” she asks me. I insist that I’ll be OK. “Let’s just finish with this,” I say.

As soon as she has climbed out of sight, I start to cry for real, shuddering and ugly, as though I have a precise number of tears to shed about this, and if I am forceful, I can finish up before Olivia gets back. As the rope slips up and up between my fingers, I try to figure out if I really want to vomit and, if so, whether I’ll be able to do so energetically enough that it’ll clear the ferns clinging to the edge of the cliff.

Olivia cleans the route. On her way down, she finds a detached bird wing tangled in the bromeliads. She gingerly pulls it out and then offers it to me in cupped hands. It is caked in blood and beautiful.

Curled up in bed the next day, nursing my shoulder as much as my grumpiness, I read a tweet about someone with long COVID. The author says their illness has changed the nature of their dreams. They used to dream about skiing or surfing, hucking off cliffs, and tucking into waves. Now, they just dream that they are afraid of these things. In one dream, they are handed a surfboard. It is crisp and wet in their fingers. They feel the elastic snap of the wetsuit around their arms. But the dream dissolves before they arrive at the edge of the water. What is left is the secret feeling hidden just beneath their grief—that no matter what they do, they will always be unsafe. Fear had eclipsed the possibility of freedom, even in the no-consequence land of their private dreams; it had killed their future, their willingness to hunger over things.

This is at least one thing that I’ve outrun. I have not gotten any wiser or more patient. But I’ve become hungrier. My shoulder hurts enough I can barely chop the vegetables for dinner or sit up long enough to finish the meal. But at least I can have this ruinous desire once again. I can want something so badly I will literally tear myself apart.

The following day, Olivia buses off to a nearby town to spend the day by a lake. I send an emergency text to my chiropractor; their reply confirms that even with my injury, swimming should be fine. When Olivia gets home, we spend hours researching surf schools in the north.

On the beach, I immediately become too sick to surf—first with a respiratory illness, then a rash, then something waterborne. Olivia posts up at a shady table with her sketchpad and colored pencils. She draws a series of hyperrealistic beetles, calls her fiancé, and drinks a lot of wine. I waste the days sucking on Advils, feeling bitter but also, eventually, a little bit smug. At least it wasn’t my brain that ruined all of our plans.

To read more from Ascent, visit our table of contents here.

The post My Rocky Return to Climbing After a Life-Changing Accident appeared first on Climbing.