Climbing Gyms Are Unionizing. What Does That Mean For Our Community?

If you swiped into Touchstone’s Hollywood Boulders at 9:32 a.m. on January 30, 2024, and looked for a manager, you wouldn’t find one. In fact, on that particular morning, every Touchstone gym manager in the Southern California region was either working from home or coming in late.

The managers who did appear in the gym that day refused to comment on what had happened the night before, but the news was out. A coalition of employees from all five Touchstone gyms in Los Angeles—Hollywood Boulders, LA Boulders, the Post, Verdigo Boulders, and Cliffs of Id—had publicly announced that they intended to form a union.

“Your employees need, and seek, a seat at the table,” read the letter sent via email to Touchstone managers and executives on January 29. The letter asked leadership to voluntarily recognize the new union, an affiliate union of Workers United, and, anticipating their refusal, stated that organizers had the 30 percent of worker signatures necessary to file for an election with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB).

Such an election cannot be legally stopped, and Touchstone executives knew that a simple majority vote would trigger the company’s legal obligation to negotiate a labor contract with the union. If the executives wanted to retain total control over their employees’ wages and working conditions, they’d have to convince them to vote no.

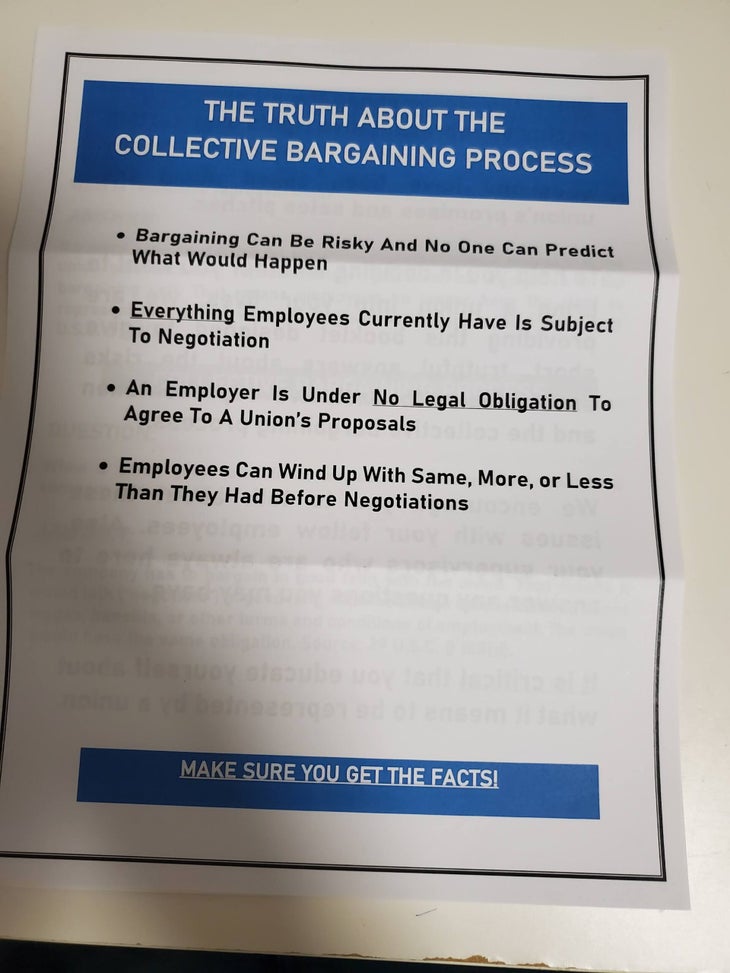

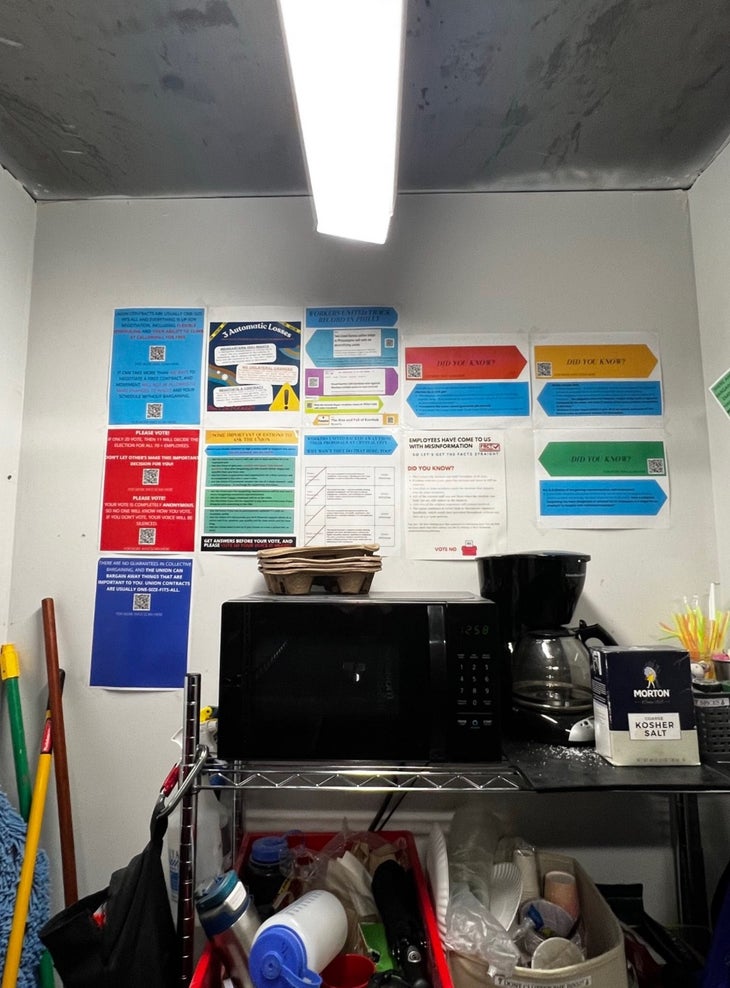

The election dates were set for March 6 and 7. Lawyers were hired. Slack messages were drafted. Anti-union flyers were printed by the hundreds, then left at the front desk and sent to employees’ homes “almost daily,” according to Jess Kim, who works at the Post in Pasadena and helped organize the opposing pro-union campaign. These colorful pamphlets included warnings such as “Bargaining Can Be Risky And No One Can Predict What Would Happen.”

Touchstone also held multiple in-person staff meetings to highlight how risky forming a union could be. “They heavily implied that the union would trade away benefits,” said Kim.

Kim and her coworkers countered with their own campaign. Throughout February, they published bubble-lettered posts on Instagram such as “7 Reasons to Join a Union” and “Union Busting Bingo,” which warned employees to beware messages like, “This will make it an ‘Us’ vs. ‘Them,’” and, “Give us a chance to fix things.” They also hosted in-person “solidarity climbs” with affinity groups that included Escalamos, ParaCliffHangers, and Queer Crush, trying to rally pro-union sentiment within each gym’s community. On Sunday nights, employees met virtually with a unionized employee at VITAL—a New York City-based gym that, since its unanimous vote to form a union in 2022, has been seen as a success story by organizers nationwide—who walked Touchstone workers through the process and implications of unionizing.

The union won 54-46 in March, making Touchstone the fourth unionized gym chain in the U.S. and pushing the number of total unionized gym locations to 15. (That number has since risen to 18).

Organizers from unionized gyms across the country celebrated Touchstone’s success on Instagram.

“Hell yes!” commented the Movement Crystal City union account, with an explosion of heart, high-five, fire, applause, and heart-eyes emojis.

However, Touchstone’s election result does not guarantee better working conditions for its employees. When employees vote to form a union, they gain the legal right to negotiate a labor contract, potentially raising wages and adding benefits once signed by both parties. However, potential downsides include paying union dues, the risk of income loss due to strikes, possible workplace tension, disagreements with union decisions, and lengthy negotiations. During the bargaining stage, which lasts until a contract is reached, negotiations may be prolonged by various factors, including proposals perceived as insufficient or disputes over adherence to NLRB laws, potentially resulting in extended legal proceedings.

Unions are still a new concept for indoor climbing. Although American gyms have seen a flurry of pro-union votes since its first in 2021, only two gym unions—Movement Crystal City and VITAL Manhattan—have spent at least a year in the bargaining stage. And their sharply differing experiences have muddled any clear picture of what this stage will look like for Touchstone.

At first, both Movement and VITAL urged their workers to vote against the union. But VITAL’s co-owner surprised employees by negotiating a labor contract that seems to work for both parties. On the other hand, Movement’s executives did not begin bargaining until fourteen months after the Crystal City union election, and they have repeatedly highlighted their first gym union’s lack of a contract in anti-union flyers posted at other Movement locations. In the meantime, five more Movement gyms have launched union campaigns in the past six months. While negotiations at Crystal City have approached a stalemate, both sides have confirmed they are still bargaining. Since August 2023, the NLRB has been investigating Movement over five charges of Unfair Labor Practices.

As the union wars spread from coast to coast, the conversations happening now—over Zoom calls, staff emails, and social media posts—will ultimately define what it means to be a professional climbing gym employee and how exclusive the sport of climbing will become.

Touchstone moves into its bargaining phase this month, and all eyes are on CEO Mark Melvin and his executive team to see which path—VITAL’s or Movement’s—they will choose.

The Money in Climbing

Today’s gym employees find themselves part of the decades-long resurgence of the American labor movement. In 2022, unions experienced the highest approval ratings among voters since 1965, and have since made headlines by bringing organized labor to blue-chip companies like Starbucks and Amazon. Unionization has raced through American climbing gyms like wildfire, more than doubling its reach every year since Movement Crystal City sparked the trend in 2021. In 2022, two VITAL gyms filed for their own elections. The next year, eight more gyms joined them across Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and New York, bumping the total to 11. Eight gyms have already voted to unionize in 2024—and we’re only four months in. At this rate, we could see 30 or more gyms pursue their own labor contracts by December.

One major reason for this spike, unionizers argue, is that gym staff aren’t sharing in the wider industry’s growth. The indoor climbing industry has boomed in the last few years, boosted partly by Free Solo’s mainstream popularity and by climbing’s inclusion in the 2020 Summer Olympics. Last year saw 48 new climbing gyms open across North America, bringing the total to 622, and 51 more are expected to open this year. The global climbing market is expected to increase by $4.19 billion from 2023 to 2027. But adjusted for inflation and the cost of living, many climbing gym employees are making less than they would have made two decades earlier, and nearly all of them make less than their local living wage. At Movement Crystal City in Virginia, the starting wage for front desk staff is $15.65 per hour, 44 percent less than a living wage in Arlington County. At Vertical Endeavors in Minneapolis, where $22.49 is considered a living wage, desk staff earn $15 an hour. And at Movement Callowhill in Philadelphia, desk staff earn a mere $13—almost $10 below the living wage. (This salary translates to $27,040 per year for a full-time employee.)

“I was getting 22 and 27 cent raises,” said PJ Haenn, a recreational climbing coach at Movement Callowhill. “Which is ridiculous for the time and effort I’ve put into the community.” Haenn has worked two seasons as a summer camp instructor for Movement Callowhill’s summer youth camp, where each pupil pays $550 per week while each new instructor (they’re hiring!) makes just $13 per hour.

“All of a sudden, there’s so much money in climbing,” said Alexa Zielinski, who helped organize the December 2023 union campaign at Movement Gowanus. “Fifteen years ago, [climbing gyms were] a passion project for everyone involved. But now there are people in it who are making a lot of money and expanding and changing the industry in a way that’s really significant. We started to see how this community we loved so much was not necessarily going to be immune to all of those forces.”

Gowanus, a former Cliffs gym, is one of nine gyms that Movement acquired and rebranded in 2023. To some workers, being incorporated into a private equity-owned corporation represented a power shift away from themselves and their local managers.

“We don’t feel like private equity represents us and our needs on the ground,” said Zielinski.

[Also Read: How Climbing Gyms Lost Their Soul]

This distance between decision-making executives and their on-site workers has exacerbated a longstanding question about whether gym staff ought to be considered skilled or unskilled labor—and what sort of pay ought to go along with that designation.

“Climbing is a risky sport,” said Kim. “In this industry, none of the positions could be a job where you come in with ‘no skills’ or no knowledge. Right off the bat, our lowest position is teaching classes. You’re teaching a life-or-death situation of how to belay safely, fall correctly, and make sure nobody [gets hurt].” When safety staff are on the floor, she added, “You have to be able to just walk by and know that this person is climbing safely, which is something you get from years of experience.”

At Touchstone, members pay $60 and non-members pay $90 for a one-hour private lesson, but the instructors—usually front desk staff—receive about $30, regardless of how much their pupil is paying. There’s an even greater disparity at other gyms, such as Vertical Endeavors, where teachers earn the same hourly minimum wage rate teaching classes that they’d make at the front desk.

The extent to which this gap between revenue and employee pay feels tolerable is directly tied to how (and if) wage growth increases in step with inflation. Professor Ahmed White, who teaches labor law at Colorado Law, says that inflation is “a very big factor” in rising union activity across the U.S. “Workers, in general, tend to be more easily motivated to organize if they feel like something’s been taken away from them,” he said. “What inflation does is change the terms and conditions without people doing anything.”

That’s exactly what we see in modern commercial gyms. In 2006, Planet Granite San Francisco paid their beginner routesetters $16 per hour, which is worth $24.63 in 2024 dollars. Today, that location is owned by Movement, and beginner setters are still earning only $23.00, which means they have nearly 7 percent less purchasing power than they would have had in 2006. Meanwhile, the price of renting a one-bedroom or studio apartment in San Francisco has more than doubled since 2006.

“A lot of my coworkers have credit card debt that’s pretty overwhelming,” Kim said. “Some full-time people have to live with their relatives because they can’t afford to live on their own. Some employees, by choice or by necessity, are living in their vans or cars. Some employees have been using food stamps or don’t have health coverage.”

One former staff member at Touchstone, who has asked to remain anonymous, told Climbing that she involuntarily found herself “living in my car in the gym parking lot” for about a month last year while working between 35 and 40 hours per week. Her pay rate, $20.25 per hour, was 24 percent less than the $26.63 living wage for Los Angeles.

“I was working at multiple gyms, covering shifts, picking up as many hours as possible, and still having a really hard time,” she said. After a month of housing instability, she found an affordable room “far out of the city. That was the only option that was available to me on climbing gym wages.”

Faced with their current rates, it’s no surprise that when Touchstone’s staff weighed the fact that the average union worker made 16 percent more than their non-union counterparts in 2023, they opted to organize.

The VITAL Experience

As Touchstone workers prepare to bargain, they hope their CEO Mark Melvin and his executive team will emulate VITAL cofounder Nam Phan’s approach to negotiations.

Phan has never been a pro-union advocate at VITAL. In fact, when two VITAL Manhattan gyms announced their intent to unionize in September 2022, Phan urged them to vote no. Phan’s general manager sent a tongue-in-cheek email to the entire VITAL staff one month before the election. The subject line was, “Please, join a Union,” and the body of the email included the lines, “If you ever find yourself a nameless, faceless drone on a giant factory floor, please, join a union…If, however, you find yourself part of a small team of nice people working hard to do something kinda fun, then perhaps consider that it might not be the right time to join a union.” A smiley-face emoticon punctuated the sentence.

But when workers didn’t take the joke, voting 13-0 to unionize, Phan and his management team accepted the result. Over the next year, they showed up to monthly negotiations “in very good faith,” according to the VITAL union’s attorney, Eric Chaikin, who described Phan as “receptive but firm.”

“VITAL hasn’t engaged in many of the terrible, union-busting tactics that you see in many other industries,” said Trevor Goodwin, a front desk worker who sits on the bargaining committee. “[They] genuinely tried to play ball with us.”

While other gyms have warned aspirant unionizers that unionizing would prevent management from giving raises, VITAL Manhattan went ahead and increased pay for all Manhattan workers three times during the negotiations period without any legal issues. (Phan and Chaikin confirmed to Climbing that the three raises were given with the union’s permission.)

On February 16, in a widely anticipated moment for organizers, VITAL Manhattan signed its first labor contract, cementing the gym’s identity as the climbing industry’s poster child for successful bargaining. The three-year contract sets the minimum pay for new crew members to $18 per hour, bumping that to $20 after one year. A new system of additional raises and minimum pay bumps will guarantee that 2023 hires will make at least $23.50 per hour by 2027. It also ends at-will employment, freezes the company’s current contributions to health coverage, guarantees excused absences for weather emergencies, offers twelve hours of accrued paid time off, creates a joint labor and management council, and restricts the involuntary reduction in working hours.

Nearly every climbing gym union member I spoke with was familiar with the details of VITAL’s contract, calling it an inspiration for their own.

“We really liked how VITAL set out wage increases over the next three years because it’s very clear what those raises would be,” Kim said. “We’re very excited about that. It proves that it can be done, and that it can be done on a shorter timeline. Obviously, Movement hasn’t come to the negotiating table, so having that in the back of our heads wasn’t very encouraging.”

The Movement Experience

It’s unsurprising, perhaps, that Movement, as America’s largest climbing gym chain, would be the first to see its employees form a union. Since 2017, Tengram Capital Partners, a private equity firm with eight other companies in its portfolio—five skincare or makeup brands, two clothing brands, and one fitness app—has steadily merged Earth Treks, Planet Granite, Movement, and the Cliffs into one massive corporation that controls 5 percent of American climbing gyms. Movement Climbing, Yoga, & Fitness now has 30 separate locations, three new gyms in development, and over 2,000 employees. It’s a certified gympire. But the vehemence with which they have combatted their emergent unions has surprised employees and observers.

In November 2021, about a dozen workers from Movement Crystal City voted 28-14 to form a union—the first of the industry. Movement immediately filed three objections to the election. By July 2022, the NLRB had overturned all three objections and certified the union. It took another six months to exchange requests for information and finally nail down a bargaining date of January 25, 2023.

According to Gus Mason, a five-year front desk worker who sits on the bargaining committee, the union began by suggesting only “non-economic” proposals such as a 15-minute break, a just-cause termination policy, a policy of non-interference for union elections at other gyms, and a 30-day notice for changes to the employee handbook. Mason called Movement’s representatives “resistant” to these changes. “They were shut off to anything that wasn’t legally required of them,” Mason said.

Meanwhile, the company began treating Crystal City differently than the other gyms under the Movement umbrella—a sign that Movement execs intended much of its union battle to take place outside these bargaining meetings. Crystal City organizers first noticed these exceptions in November 2022, when Movement “started a new [annual review] process at other gyms that they did not implement in Crystal City,” according to Mason. In this new process, workers received evaluations between July and August; if their evaluations were acceptable, they got raises in September. But Movement didn’t apply this process to Crystal City, “telling folks one-on-one or in other settings,” according to Mason, that they “couldn’t give raises” because of the union.

View this post on Instagram

On May 24, 2023, Movement Crystal City’s gym director officially announced this policy, writing in an email that annual reviews would be “on hold during the union bargaining process.” Effectively, this meant that until a contract was reached, Crystal City workers’ pay would remain at October 2021 levels.

Organizers responded with their own all-staff email. “You may have heard that Movement can’t give any raises because of the bargaining process right now,” they wrote on July 6, underlining the next sentence: “This is not true.” Mason claims that the union had already given a letter to Movement explicitly waiving any legal objections to pay raises. After the rebuttal, Movement “changed the messaging,” Mason said, “saying, ‘Legally, there’s nothing stopping us [from giving raises], but we don’t want to do it until we get economic proposals from the union.’”

In another email, this one sent on July 14, Movement Crystal City’s gym director reiterated that Crystal City would skip the annual reviews and raises for a second year. His language was careful; he blamed no specific law but still emphasized that the situation was caused by the union’s existence. “We need to bargain the raises and cannot make any changes in compensation until we see and understand the union’s full position on pay and benefits,” he wrote. “Providing raises without a complete economic proposal from the union would be like buying a house without an inspection.”

To get that process moving again, the union delivered its full economic proposal the very next week during a July 21 bargaining session. Still, Movement executives did not lift their suspensions on raises. Instead, on July 24, the Crystal City manager confirmed to staff that annual reviews would remain “on hold.”

Between the Law and a Hard Place

The practice of suspending raises for newly unionized workers is not new, but the NLRB has often—though not always—ruled that it constitutes illegal retaliation. In October 2021, amidst a wave of new unions in Starbucks stores, Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz announced that all Starbucks employees would receive a new minimum wage of $15 per hour. Employees with two or more years of tenure would get three percent raises—excluding workers at the stores that had declared their intention to unionize. Federal law, Schultz claimed, “prohibits us from promising new wages and benefits at stores involved in union organizing.”

Schultz’s attorneys cited Section 8(a) of the National Labor Relations Act, which bans employers from unilaterally changing the terms and conditions of employment without first consulting with the union representative. They argued that giving raises to unionized workers was a unilateral change that would land Starbucks in serious legal jeopardy.

However, Professor White points out that it’s the intention behind the change that matters; that’s what the NLRB examines to decide its legality. Section 8(a), he says, allows an employer to make unilateral changes, such as raises, “if the union accedes to the change” without issue. By contrast, withholding raises could actually constitute a violation of Section 8(a) if it is accompanied by “indicia of anti-union animus.” In other words, if withholding raises is part of broader, non-discriminatory budget cuts or applied consistently to both union and non-union employees, it may not be deemed illegal or retaliatory. But if withholding raises seems intended to undermine the union and disincentivize would-be unionizers, it’s likely to be deemed an Unfair Labor Practice.

And, as it turned out, the Starbucks case ended badly for Schultz. In her widely covered September 2023 ruling, NLRB Judge Mara Louise Anzalone skewered Starbucks’s rationale, writing that it “ignores… basic aspects of the law,” such as the fact that “[Starbucks] could have simply asked the Union for permission” to include unionized employees in the new raises and benefits package. She ordered Starbucks to provide nearly 10,000 unionized workers two years’ back pay.

When Climbing asked Movement to confirm whether the company had received the union’s letter waiving any legal objections to annual raises, the spokesperson responded, “This is counter to what equitable negotiations should be, as we are still negotiating pay rates and still do not know what those rates will finally be.”

Judge Anzalone affirmed the “general rule” that “in deciding whether to grant benefits while union organizing is underway, an employer should act as it would if a union were not in the picture.” The climbing industry has seen this in practice at VITAL, which provided raises three times during its bargaining period.

When asked why Crystal City did not receive the same annual reviews and raises as other Movement gyms, the company responded, “Since the [Crystal City] employees are represented by the union, [reviews and raises] are subject to negotiations.”

Touchstone workers told Climbing that organizers at Movement and VITAL warned them of the possible threat to raises that the company might make.

On the Touchstone union’s “Union Busting Bingo” board on Instagram, “No Raises During Negotiations” takes up one turquoise square.

The Gympire Strikes Back

Throughout the summer of 2023, as Crystal City’s bargaining meetings continued monthly over Zoom, Mason’s cautious optimism was steadily extinguished.

Movement was not responding well to the union’s offers, as Mason had initially hoped. When the union asked to increase minimum pay from $15.65 per hour to $16.80—and later, when this initial proposal was rebuffed to $16.00—Movement countered by making what Mason calls an “aggressively low” proposal: to reduce the minimum pay to $13.00 per hour.

The union was outraged.

“We were asking them, ‘Why? Is the business doing poorly?’” said Mason. He says the company refused to provide financial reasoning for the proposed wage cuts. “They said, ‘Folks should not be surprised that management has taken a hard line on wages—that if you’re bargaining, it’s not guaranteed to start at the status quo.’”

Even more shocking to organizers was the second part of the company’s proposal: that staff gym memberships would no longer be free. “I don’t think they believe that cutting free memberships for staff will do anything other than make people quit,” Mason said. “That’s the main reason people work at climbing gyms.”

Gym membership prices are arguably our sport’s primary barrier to access. VITAL, for example, now charges $145 per month, Touchstone charges $99 with a $100 initiation fee, and Movement LIC charges $135 with a $49 initiation fee. Without gym memberships, climbers lose their training space and their in-person social network.

Lucho Rivera, a professional climber with a long list of first ascents spanning from Yosemite to Malaysia, weighed in on Movement’s proposal. Before he made his name in multi-pitch trad climbing, Rivera worked for five years as a routesetter for what is now Movement San Francisco. “I was a young man living on my own,” Rivera said. “I was broke as fuck. It was very important to me that I climbed there for free. Especially as a setter. Can you imagine creating a route and having to pay to climb it?”

By late summer, the union was fed up with Movement’s refusal to withdraw from their below-status-quo wage proposal. A contract was nowhere in sight, and Crystal City workers still hadn’t received raises in two years. On August 30, with the help of Workers United, the union filed five Unfair Labor Practice charges against Movement. These allegations included surface bargaining, retaliation, modification of contract, coercive statements, and changes in terms and conditions of employment—charges that, taken together, address Movement’s executives’ behavior both in and out of bargaining. Like the Starbucks employees, Crystal City workers are hoping for back pay if their NLRB case succeeds.

A spokesperson for Movement declined to expand on the company’s intentions in proposing to cut free memberships and lower pay rates, but she did insist that “this back-and-forth is a standard part of bargaining.” Regarding the Unfair Labor Practice charges, she wrote, “We dispute them completely, and we look forward to presenting our position to the NLRB.”

On Instagram, the Crystal City union has posted several infographics detailing Movement’s latest offers, including the $13.00 suggestion.

“Where are the good faith negotiations?!” commented the Touchstone union.

Look At Crystal City—No, Not Like That

Over the next eight months, as five more Movement gyms filed for their own union elections, organizers and their bosses became fiercely engaged in a publicity war over what was happening at Crystal City. Each side argued for a different interpretation of Crystal City’s struggles—namely, their suspended raises and lack of a contract.

Union organizers suggest that Movement may be misinterpreting the law to blame the union for the lack of raises, potentially to discourage other gyms from unionizing. “If I had to guess at company strategy, it’s to make it look as painful as possible so that other gyms like Callowhill and Gowanus are disincentivized from unionizing,” Mason said.

However, in flyers and internal communications, Movement managers pushed a simpler cause-and-effect interpretation: Crystal City unionized, and now Crystal City faces the inevitably negative consequences of that decision.

So who was right? More importantly, whom did the Movement employees believe?

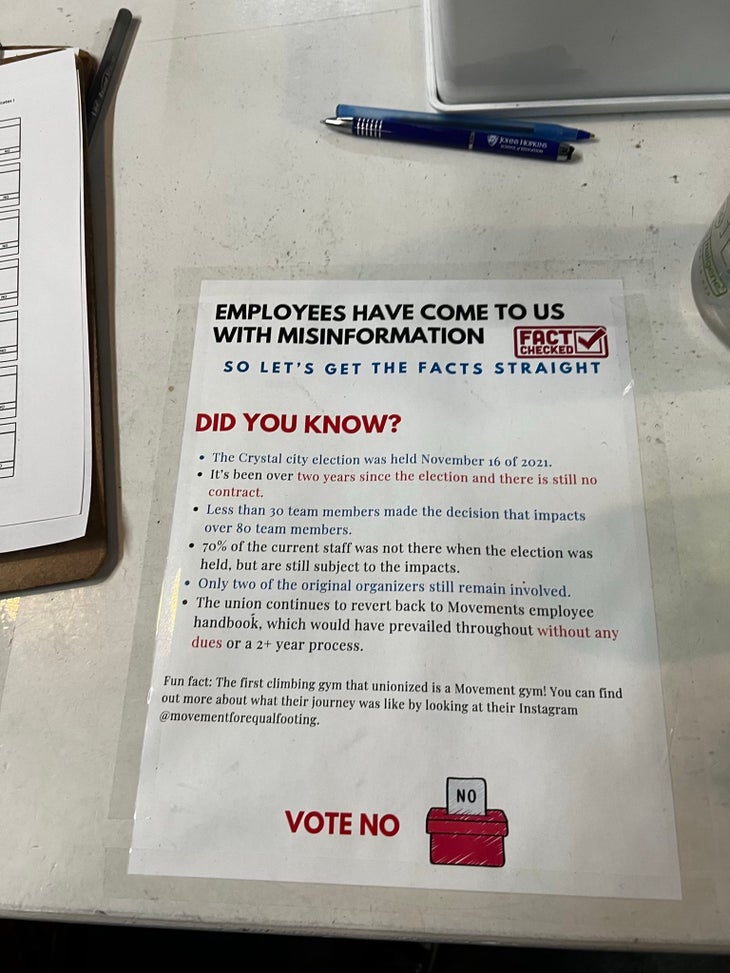

After Movement Callowhill became the second Movement gym to file for an election in November 2023, PJ Haenn and Dana Lavin came to work to find laminated flyers taped down to the front desk, right below the computers. “The Crystal city [sic] election was held November 16 of 2021,” the printed message warned. “It’s been over two years since the election, and there is still no contract.”

“The people at the front desk were sick of it,” Lavin said.

Movement executives directly repeated this message in videos. In a selfie-style clip that was posted to Callowhill’s internal scheduling app on December 4, Stephanie Ko, Movement’s Executive VP of Operations, introduces herself to Callowhill workers. When she starts discussing union business, her voice becomes low, and her eyes widen. “At our Crystal City gym, we have a union,” she says, shaking her head sadly, “and I’ll be honest: it has not been a success story.” Ko then encourages workers to “think about the consequences of voting for a union. At Crystal City, as a result of the contract, they may have to pay to use the gym—even as a team member.” Her voice raises in disbelief, and she twists down one corner of her mouth as if pained by the thought.

Suddenly, Ko smiles brightly. “Here’s what I propose,” she says, leaning toward the camera. “Let’s forge a different path together. Instead of opting for a system that’s proven problematic, I invite you to be part of what we’re creating here at Movement.” She’s still beaming when the video cuts out.

Two days after this message, Movement Callowhill voted 39-15 to unionize. Ko’s video was promptly removed.

But the drama at Callowhill wasn’t over. In last winter’s #JacketGate scandal, Movement promised free Mammut jackets as a December bonus to all former Cliffs staff but then decided after Callowhill’s election to exclude Callowhill staff from that gift. Haenn and Lavin said the jackets were worth over $200 each.

“We have not passed the new Movement jackets to staff,” wrote the Callowhill gym director on December 24, “because of legal requirements related to the status of the union election. I’m sure this is disappointing but is a situation we cannot avoid at this time.” Haenn and Lavin confirmed that Movement did not seek permission from the union to distribute the jackets.

In early May—five months later—a Movement spokesperson told Climbing that the jackets “will be distributed” to employees at Callowhill.

In the publicity war against Movement executives, organizers have a few advantages: Instagram, where all union accounts regularly interact with each other and share each other’s posts; their Workers United lawyers, who are seasoned at negotiating with huge corporations; and, finally, their colleagues at VITAL, who have given them a real-life template for negotiating a contract in good faith. Their disadvantages include internal communications, which managers control.

But email is a neutral ground, and last winter, at Movement Gowanus, one reply-all thread turned into a battlefield over the truth.

On December 28, 2023, Gowanus organizers emailed the full staff to announce their union campaign—the third one beneath the Movement umbrella. Two weeks later, the Gowanus manager responded, saying, “Unionization will have far-reaching implications for our entire community,” therefore, the company would not provide voluntary recognition.

Gowanus organizers invited Aaron Vanek, a VITAL Brooklyn employee and organizer, to reply all. “I’m a member of the Workers United organizing committee, where we successfully won our union in July,” Vanek wrote, adding that he agreed with the Gowanus manager. “Unionization does have far reaching implications for the community.” Then he listed the benefits that VITAL Manhattan’s contract had included, such as strict wage increases, a joint labor management council, and protection against reduced hours. “Solidarity, Aaron Vanek,” he signed off.

The next day, the Gowanus manager sent back a long and emphatic response.

“I’m happy that VITAL’s employees are content with their bargaining,” he began. “The fact is, a union at Gowanus will not be bargaining with VITAL—it’ll be bargaining with Movement. Based on all I’ve heard, Movement intends to negotiate assertively, and there’s no reason to believe that what happened at VITAL will necessarily happen here.”

“A better comparison,” the manager wrote, “would be between Gowanus and Crystal City—Movement’s first unionized location. I’ve done some research on how a union has affected Crystal: The union was voted in in 2021, and both parties are still bargaining. Unit members have not received raises in the entire period.”

The manager went on to call the Crystal City union “disorganized,” claimed that they “moved backwards on pay,” and warned that the union “risks losing” benefits like free memberships and guest passes for employees.

Several days later, Gowanus union organizers published a Google Doc headlined “Claims vs. Facts” and responded to each part of the manager’s email. “Movement violated the law when they denied raises to the employees at Crystal City for over two years,” they wrote. Regarding the loss of free memberships, they emphasized that perks can’t be taken away in bargaining unless the union agrees.

“This is meant to scare us,” the organizers declared.

According to election results, however, it did not. On February 5, Movement Gowanus voted 36-2 to unionize, following the pattern set by Movement Callowhill and Movement Crystal City. By April, three more Movement locations in Chicago and New York—Lincoln Park, Wrigleyville, and Long Island City—had voted by over 83 percent margins to unionize, too. In the next few months, Movement executives will be facing six separate unions in bargaining.

“I will not be a union-busting CEO.”

After Touchstone’s five LA locations declared union campaigns in January, Touchstone’s management launched a well-organized “Vote No” campaign that, in many ways, resembled the campaigns conducted by Movement at their Callowhill and Gowanus locations.

“They’re an extremely wealthy company,” said Kim in February, before Touchstone started mailing out information packets. “They’re opening new gyms and have lots of financial resources. I expect them to battle legally.”

But unlike at Movement, Touchstone’s original cofounders, Mark and Debra Melvin, still hold the CEO and COO positions, and they’ve been heavily involved in California’s climbing community since 1995. Perhaps this is why, on March 11, four days after Touchstone voted to unionize, Mark Melvin personally acknowledged the results.

“As I have said throughout the campaign, I will not be a union-busting CEO,” he wrote to his staff over Slack. “As Touchstone moves to start the negotiations with the union to reach a first contract, we are dedicated to finding a contract that both meets the needs of the staff while protecting all the stakeholders at Touchstone.” Kim added that right before the election, employees also received an apology from Melvin “about sending too many packets to our houses.”

Even as Touchstone indicates that it may take the VITAL path, other recently unionized gyms seem to follow Movement’s example. After five Vertical Endeavors locations in Minnesota declared their intention to unionize in August 2023, front desk worker and youth coach Ellie Fedor was approached by her facility manager, the company Vice President, and an outside labor consultant during her break. In an audio recording obtained by Climbing, her facility manager and the labor consultant both insisted that unionizing would lead to a pay freeze for workers. “We cannot alter terms of employment, so we can’t adjust anybody’s pay,” said the manager. Fedor told them that status quo raises did not violate any law, but the labor consultant insisted otherwise. In November, Vertical Endeavors workers voted 54-12 to form a union, but management has at least partially stuck to the no-raises concept. In September, Fedor was promoted from counter staff to part-time shift manager, but she has still not received the raise to $16.50 per hour that usually accompanies the position. “My manager told me verbally that he thought the union was why,” she said.

The Vice President of Vertical Endeavors, Jason Noble, declined to comment on any union-related topic.

Fedor told Climbing that the union is prepared to file Unfair Labor Practice charges, just like Movement Crystal City, but that they are holding off in the hope of no longer delaying bargaining. “The hesitation is just that any legal action takes so long,” she said. “But we will use it if we need to.”

The Future of Climbing Gyms

2024 is primed to be a defining year for climbing gym contract negotiations. Touchstone’s five-gym union, Vertical Endeavors’s six-gym union, six separate Movement gym unions, and VITAL Brooklyn’s union are all starting or continuing into their bargaining periods. In addition, the NLRB’s forthcoming ruling on the Unfair Labor Practice charges at Movement Crystal City could determine whether the biggest climbing gym network in the world will maintain its hardline, anti-union strategy or—like Starbucks finally did in February—start making concessions.

If unions continue to grow across indoor climbing gyms, gym staff positions could transform into steady union jobs, enabling youth coaches, routesetters, janitors, instructors, and front desk staff to negotiate for wages and benefits that support sustainable, full-time careers. The increased labor costs, however, could pressure gyms to focus on higher-revenue elements of the business. Alternatively, gyms might pass on increased labor costs to gym members and day users, possibly making gyms more expensive. The growing popularity of unions could also affect adjacent industries such as guiding and tourism, prompting discussions about labor and compensation in the outdoors.

However, if gym executives succeed in stalling bargaining and wearing down organizers, the current union trend in climbing may burn out before any more contracts can be signed. We’ll see union Instagram profiles go stale, wages stay frozen through inflation, and climbing gym jobs persistently categorized as “unskilled,” at-will positions with minimal rates and stability.

Profits may continue to rise without the impact of high labor costs. Minimum wages that are not sufficient to cover living expenses could deter underprivileged people from taking gym jobs, even if this is the only way to access climbing due to increasing membership prices. This trend might make climbing more exclusive, particularly for people in urban areas without easy access to outdoor climbing.

Looking forward, Zielinski said that her Gowanus coworkers are prepared to face the same bargaining difficulties as Crystal City to achieve their vision of the future.

“We believe that the climbing industry should move in this direction,” she said. “[Movement executives] think that if they just drag their feet enough, this will just go away. I think they’re wrong and underestimate how much people care about this community—and how passionate they are.”

[Also Read: How Indoor Climbing Became a Boondoggle]

The post Climbing Gyms Are Unionizing. What Does That Mean For Our Community? appeared first on Climbing.