A Story Of Hope: How Climbing Lifted Kids Out Of The Slums Of Rio

“The first impression I had was that if I fell, the rope would snap and I would die,” 18-year-old Rodrigo Alvez said about the first time he went climbing.

“My parents think I’m crazy … and that I should be like everyone else and just go get a normal job,” his friend Caio César added. Alvez and César are team members at the Centro de Escalada Urbana (CEU), located in a favela (slum) on the south side of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The persistent naysaying of their parents exemplifies the universal anxieties sometimes heard at crags and gyms.

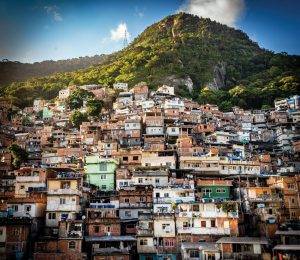

We came to Brazil to escape the never-ending winter in the Sierra Nevada, rock climb, and get a taste of Brazilian culture. We would climb on Rio’s 1,000-foot-plus beachside granite domes, crag on the steep limestone of Serra do Cipo, and, of course, dance in the streets during Carnival, Brazil’s week- long party that enlivens the streets each spring before Lent. Our host, Andrew Lenz, is an old friend of Matt’s and is one of the founders of CEU. He moved to Rio from Houston at age 17 when his father got a job in the city.As the scorching summer sun rose that morning, the layered buildings of Rocinha sat protected in the shade for a few precious hours. We wandered up meandering streets, dodging motorcycles and street vendors, the density closing in. Narrow alleys, homes and businesses built up like Tetris pieces filled every available space, and people on foot were everywhere.Rodrigo and Caio have lived their entire lives in a favela named Rocinha—pronounced Ho-seen-yah—where CEU is located. We met them a few days after arriving in Brazil at Andrew’s encouragement. When we asked the taxi driver to take us to Rocinha from a nearby neighborhood where Andrew lives, he replied, “You don’t want to enter the favela, do you?” When we got there, his last words to us were, “Tem cuidado!” Which translates to, “Be careful!”

After 10 minutes of tortuous twists and turns in the roads, we found the unnamed alleyway where CEU, pronounced ‘seh- oo,’ is located. CEU, meaning “sky” or “heaven” in Portuguese, is often just referred to by its members as The Project. There, in a small storefront, The Project built a tiny bouldering wall.

•••

The city of Rio, with 12 million inhabitants, chaotically fuses urban living, granite big walls, and Amazonian-esque jungle with dreamy beach-scapes. The city has acceded to the topography, cramming pockets of buildings in between sandy shores and craggy, lush mountains. The poor, pushed out of the expanding city center, have retreated up the heavily vegetated slopes. As the favelas have grown, many have climbed to the point that their urban edges abut the base of the large rock formations that sporadically interrupt the modern sprawl of Rio.

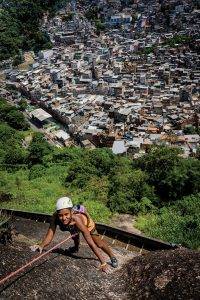

This is how Rocinha came to be nestled halfway up one of Rio’s most prominent mountains; there was nowhere else to go. Despite spending their entire lives looking up at the nearly 1,000-foot granite headwall that tops Irmão Maior, the kids from CEU had no concept of climbing. “I honestly didn’t know that there was climbing on Irmão Maior … I didn’t know anything about climbing at all,” said Gabriel Lima, 18.

That all changed nine years ago when Andrew started CEU with his friend Asa Firestone in the hopes of sharing with the kids what climbing had given him.

Brazil ranks ninth in the world for worst income inequality, which makes a sport like climbing financially inaccessible to most people. Compounding the problem, rock gyms, which in the United States serve as an entry point into the sport, are scarce. As of this writing there are two small gyms in Rio, not including CEU, each with little roped climbing. Both are in expensive neighborhoods with limited access by public transportation. But CEU and its little bouldering wall tucked up a narrow alley in Rocinha? It’s free to anyone that can get there.“Here, even more so than in the U.S.,” Andrew said, “climbing is an elitist sport. If you’re poor, you don’t climb. All the climbers here tend to be white and middle class. I wanted to shake that up and give access to the sport, the lifestyle … the self esteem, self awareness, health, and environmental awareness that is just so deeply rooted in climbing.”

Maintaining The Project hasn’t been easy. Although technically under the jurisdiction of the policia militar of Rio, favelas practically govern themselves. And in Rocinha, and most of the other favelas of Rio, “governance” comes in the form of gangs and is accompanied by instability and violence.

“Rocinha went through a six-month-long turf war last year that saw over 60 registered deaths. It’s been kind of sketchy to climb [on the face of Irmão Maior], although we are slowly starting to venture back,” Andrew said. The mountain of trash piled below a makeshift playground is further evidence of the political neglect plaguing the favelas.

Violence is only one part of the challenge. Trying to “promote change [through climbing] for kids in these tough situations,” Andrew said, means fighting against the cycle of poverty by encouraging them to “finish school and invest in more long-term plans.”

To help, CEU sponsors a mentorship program for a few of the kids. According to Andrew, the program aims to “help the kids get organized, have access to resources and create opportunities to break the cycle of dropping out of school for low wage and insecure jobs.” Over the years, CEU has helped with employment and networking, funded additional educational tutoring, and created accountability in school attendance. Those involved in the mentor program receive a monthly stipend and in return they must stay in school and help run the 10 x 30 foot bouldering wall in the heart of the favela. They open and close the facility and coach the less experienced children who use the wall. Hundreds of children have been exposed to the sport through The Project’s free bouldering wall and those who take a keen interest have the opportunity for mentorship and fully-funded outdoor climbing trips around Rio.

•••

Andrew is an old-school trad climber at heart who learned to climb in Rio and over the years he has put up new routes, completed big route link ups, and set the speed record on Sugar Loaf, the city’s most famous climbing destination.

Rio has a rich climbing history that can be traced back to 1914 and is based primarily on ground-up, runout, multi- pitch routes that ascend the urban cactus-covered domes. Influenced by European travelers in the early 20th century, Rio spawned a unique flavor of climbing, creating its own grading system and up until recently, shirking the global popularity of bouldering and sport climbing.

Andrew had hoped to turn the kids into big-wall aficionados. “The most rewarding moments for me have come from big days in the mountains. When you learn to keep it together when you are tired and scared, that becomes a source of strength that you can draw upon in all aspects of life,” Andrew said. But as the kids and the sport crags around the city have blossomed, sport and competition climbing became their favorites.

“What most motivates me are the competitions,” Mateus Martins says. “I get crazy and it makes me want to climb more.”

Mateus, 20, has been a part of CEU for the last four years. Through a modest additional scholarship from The Project, he now attends a private school outside of the favela. “Climbing and CEU changed me completely,” Mateus said. “It started to change the way I see my fears and how I can deal with them, by facing them and talking about them. It has helped me get to know myself better.”The competitions, hosted mostly by the Brazilian Association for Sport Climbing, take place in cities all over the country and the kids from The Project have been able to travel and compete because CEU provides the funds. Rodrigo came in first place a couple of years ago at the youth level and his teammate Caio aspires to make the Brazilian Olympic climbing team. Perhaps in a nod to Andrew, Caio also dreams of climbing in Yosemite one day. “I don’t care if it’s El Cap or Half Dome. Both are so incredible.”

•••

Whether it is through guided trips up Rio’s classic multi-pitch routes or pulling hard on plastic, the original lessons CEU aimed to teach the kids shine through. Victória dos Santos, the first female in the mentorship program, credits climbing and The Project with helping her overcome her shyness. Gabriel notes that climbing changed his way of seeing nature, teaching him how to care for the environment. And Rodrigo said that The Project has “changed the way I think, the way I treat people and the work opportunities that are presenting themselves now.” These global lessons of climbing resonate even louder in the Brazilian favela.

As we walked into CEU that first morning, heavy clouds pushed past and obscured Irmão Maior. The team was wrapping up a meeting with Andrew, discussing, among other things, the beginning of their weekly “girls’ night.” Victória began to coach some younger kids through a warm-up routine and the older boys initiated a game of “add-on” with Matt, chalk flying as young muscles pulled off acrobatic moves.

As an intense rain fell, dropping the temperature a few degrees but increasing the already sweaty humidity, Andrew told us about the rains earlier in the year that flooded CEU and caused five reported deaths in Rocinha. “The floods are common place for a lot of favela residents. We’ve basically gotten used to it,” he said.With the metal roll-up gate open in a vain attempt at circulating some air, the gym felt physically connected to the bustling favela. Outside, the community played a constant game of shuffling vehicles and scooters through the single- lane alley. Samba music blasted from a stereo somewhere nearby and children stopped in and traded their flip-flops for the climbing shoes provided by CEU.

Fortunately, the storm on the day we visited was short-lived. By the time the clouds had finished with the downpour, our muscles were spent from over-gripping the greasy plastic. As Victória walked with us down the hill through the favela, the oppressive clouds began to break apart and the midday sun brightened the colorful favela. Water streaks ran prominently down the face of the Irmão Maior.

At the base of the cliff is where The Project began. It was there that Andrew first began putting up new routes designed specifically for kids to learn and grow on. It was there that Caio, now a 5.13 climber, made repeated attempts at a 30-meter 5.7, getting scared to the point that tears ran down his face. The failure was immediate, but the drive to get to the top kept him coming back.

With CEU there to support his innate determination, he made multiple attempts over several weeks, eventually succeeding in making his way up the climb on Irmão Maior. He triumphantly shouted from the chains, “I am the shit!”

Try Hard. Failure. Resilience. Success. These same lessons are what has helped Caio earn his high school diploma at the age of 20 after dropping out for three years.

The perseverance with climbing on the Big Brother that presides over Rocinha illustrates climbing’s broad powers to guide kids like Caio from success in the mountains to success in other aspects of life. And the ever- increasing popularity of climbing and rock gyms will only serve to help more children learn that they too can get to the top and be … “the shit!”

For information on the Centro Escalada Urbana, visit their facebook page, C.E.U. Centro de Escalada Urbana. To contribute to The Project visit www.gofundme.com/centro-de-escalada-urbana.

This feature appeared in Gym Climber #4

The post A Story Of Hope: How Climbing Lifted Kids Out Of The Slums Of Rio appeared first on Climbing.