Aman Anderson, Founder of Beast Fingers, Doesn’t Want Climbing To Exclude Anyone

This article first appeared in Gym Climber.

Getting kids off the streets and engaged in a positive and healthy lifestyle is job one for Aman Anderson.

Like many good ideas, Beast Fingers Climbing started as a sketch on a napkin when Anderson, in his early 20s at the time, was living in Washington, D.C. Talking with a close friend one day in 2010, he shared his loose plan of building a training facility for underprivileged and inner-city kids, a place where they could find refuge from the streets, be themselves, and strengthen their growing bodies and minds.

“I told my friend, wouldn’t it be so cool to put a climbing gym in the hood?” says Anderson. “I was like, I’m going to take these kids to nationals and they’re gonna win. Everybody’s gonna be surprised to see all these Black kids on the podium.”

Working as a graphic designer, he mocked up a logo. But that was where the idea for the gym literally hit a brick wall. It simply took the right timing a decade later and a partnership with adidas/Five Ten for his napkin sketch to materialize into a real facility with four walls.

Anderson doesn’t want Beast Fingers to exclude anyone.

On January 2, 2021, at the height of the pandemic, Beast Fingers opened on Broadway Street in the Globeville neighborhood of Denver. It is the country’s third Black-owned climbing gym, following Coral Cliffs in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and Memphis Rox in Tennessee. Inside, Beast Fingers has all the amenities a climber could want: hot and cold soaking tubs, campus ladder, a steep wall, pull-up bars and an assortment of training tools.

Along Colorado’s Front Range, climbing gyms are like Starbucks in Seattle. Options include Movement Climbing + Fitness, The Spot, and Earth Treks, which all charge $20 and up for day passes and $80 or more for monthly memberships—not bad, but cost prohibitive if you live paycheck to paycheck. Day passes at Beast Fingers are $10 for kids, $15 for adults. Memberships are $35 and $45 per month.

Denver may be one of the most gentrified cities in the nation, but Globeville is bordered by the South Platte River, two interstates and railroad tracks, isolating it from the rest of the city. European immigrant workers and big industry settled in Globeville in the 1800s because of its proximity to the thoroughfares. Being close to factories and segregated from the rest of Denver, today residents combat social, physical, and environmental oppression.

In the last decade, when luxury apartment complexes, craft breweries, bike shops, and hipster cafés flooded into much of Denver, some families were pushed out and resettled in Globeville. Today’s community is largely working class, and its Hispanic and Black populations are growing, according to Shift Research Lab.

Located on the neighborhood’s north end, Beast Fingers has a view of Interstate 25. Its neighbors include a hot-tub supplier, a fitness equipment dealer, a bong shop, and a new 91-unit affordable housing complex. It’s exactly the kind of area Anderson imagined where he’d serve his community.

“It’s got this rough edginess to it,” he says. “It reminds me a lot of where I grew up.”

The Trap

Originally from Orlando, Florida, Anderson, now 33, calls his hometown “the trap,” because he says Black men get pulled to the streets to join gangs. One of his older brothers spent time in jail, and Anderson says he heeded his brother’s advice to stay out of it. As soon as Anderson graduated from high school, he left for college in Virginia to study health science and desktop publishing.

While working in 2008 at his first post-grad job, in Walla Walla, Washington, Anderson was introduced to climbing by a friend who took him to a wall at a YMCA. Intrigued by this new way of moving, Anderson started going to the gym after work, and went bouldering outside the little Washington town.

Eventually, he moved back home to Orlando, and then to D.C., holding a number of product design jobs along the way. But it wasn’t until 2016, when he relocated to Denver, that he decided to create his own climbing products, the Grippūl and KörperForce. The Grippūl is a portable climbing hold isolator that quantifies climbing grades relative to grip strength when you use it with the KörperForce, a climbing strength-to-weight calculator now available as an app.

Based on Anderson’s case studies, the average climber can crimp about 60 to 79 percent of their body weight. While people can use their own hangboards, his methodologies for collecting data are one of a kind. His methods help climbers calculate the maximum weight they can crimp and pull without injury. A few researchers have tested his models to see if they could reach 100 percent of crimping their body weight in a year, and a few have done it, he says. Anderson calls his methods #GrippulTheory and there are several Reddit rabbit holes with graphs and measurements exploring the topic.

“It’s every climber’s goal to climb V10, and helping climbers see a path to it with free resources is magnetizing,” he says.

In 2018, the American Alpine Club recognized Anderson’s research and sponsored a trip to France to present his findings at the International Rock Climbing Research Association’s gathering. Around the same time, Anderson started using his proprietary training tools and methods to coach a limited number of young athletes under Beast Fingers, the name he came up with in D.C. for a training facility. He didn’t have his own space, so he leased space in a CrossFit gym called Mountain Strong. That building would become the permanent location for Beast Fingers when Crossfit moved out in 2020.

Some of Beast Fingers’s ambassadors include competitive paraclimber Maureen “Mo” Beck, American Ninja Warrior competitor Jennifer Nicely, qualified Tokyo Olympian Mickael Mawem, and a handful of kids he has trained who have ranked at regional and national championships. But behind some of the athletes’ successes, Anderson knows their hardships: some parents struggle to pay the bills, and some kids show up with holes in their clothes.

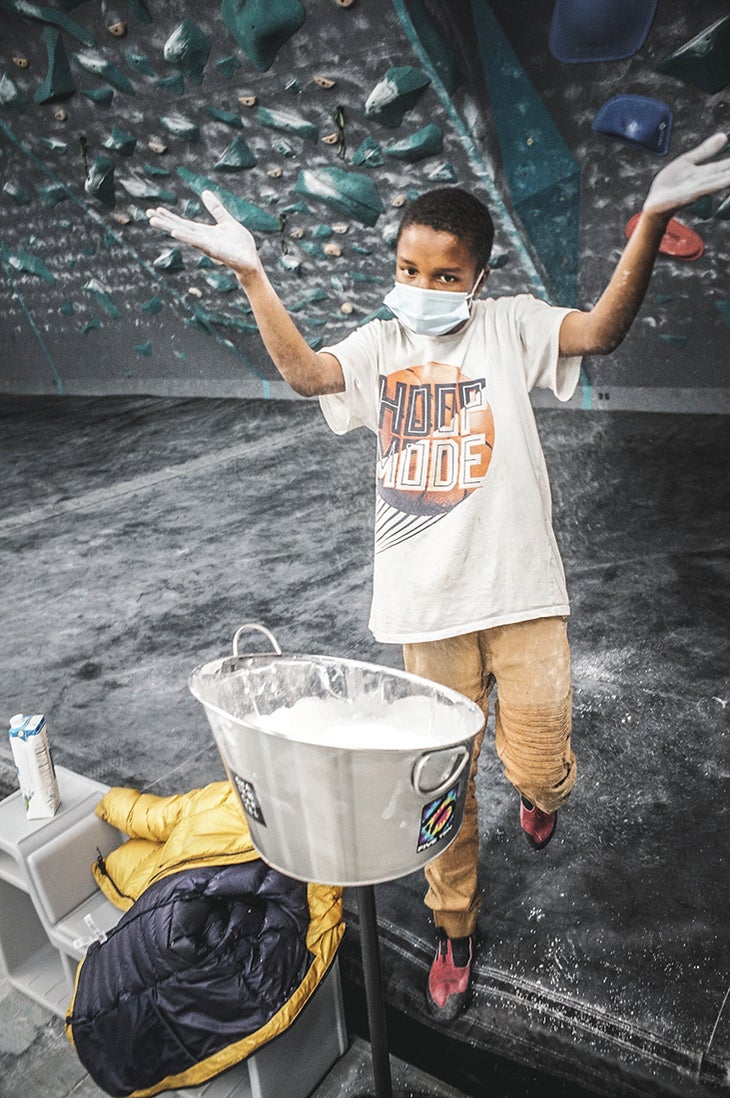

A few weeks after the gym opened, a few adidas Terrex employees, including Devon Derby, the sports-marketing manager at the time, visited with armfuls of shoes and apparel to give to the kids. “It was a touching moment when I handed one of the boys, Taveon, a full outfit,” says Derby. “It’s hard to say what his walk of life has been, but he was beside himself. He was like, ‘Are you sure these are mine?’”

That was an eventful day for the kids of Beast Fingers, says Anderson, “They were so happy.”

Anderson doesn’t want Beast Fingers to exclude anyone. In addition to offering $10 day passes for kids, he has a pay-what-you-can policy to families in need. He hopes to expose kids to the sport and healthy lifestyles. But if climbing only keeps them off the streets, that’s all right with him, too. Soon, Beast Fingers will also have a nonprofit arm so it can partner with other local organizations and raise money for additional programming.

Long ago, when Anderson was growing the Boys and Girls Club provided a safe space for him. He sees his fitness center as providing the same kind of haven for kids and families in Globeville and greater Denver—it’ll just be one with colorful plastic climbing holds, chalk dust, and racks of weights.

The post Aman Anderson, Founder of Beast Fingers, Doesn’t Want Climbing To Exclude Anyone appeared first on Climbing.